Cultural champion Ken Gorbey 'spreading out' his ninth decade

31 October 2022

Arts alumnus Ken Gorbey tells Megan Fowlie he is treating his ninth decade as he would a museum exhibition: he’s determined to make it an engaging experience.

Perched on a craggy hilltop overlooking Wellington’s wildlife sanctuary is New Zealand’s “rarely spotted Gorbey”. It’s not a bird but archaeologist-turned-museologist Ken Gorbey. He gained the moniker years ago, as watchers snatched glimpses of him rushing between meetings to hasten the opening of Te Papa in 1998.

His movements are closer to home these days. He settles into his office every morning.

“Don’t laugh,” he says. “I’m writing a novel.”

He suggests it is a possible affliction of age.

The octogenarian says that rather than celebrating his birthday, he is enjoying his ninth decade so he can “spread it out”. It speaks volumes of his penchant for creating an engaging enduring experience of the present.

Ken grew up around Waikato and Auckland. His father, a teacher, moved every two years. In the late Sixties, he attended the University of Auckland, in the same year as Dame Professor Anne Salmond.

He recalls Anne as the shining star. “I was always coming up the rear.”

He puts down the decision to go to university at Auckland as a case of lacking imagination.

“It was just a bus ride away.”

The truth though, was Auckland was still not his first choice. He had saved £1,000 to buy a Volkswagen and trot across Asia over to London. But his four compadres got married.

“Idiots,” he calls them. “They saw the romance in the opposite sex, not travelling to India.”

Museums were a good way of doing archaeology.

After completing a double degree in anthropology and cultural geography, followed by a Master of Arts, Ken worked on the Kapuni gas line, then became director of Waikato Museum, from 1969 to 1983.

“Museums were a good way of doing archaeology,” he says.

But it wasn’t going to last. Waikato Museum took Ken into his lifelong career of cultural management. He was “captured” by the intellectual side of management, and the writing of scholars who were “futurologists”.

At the same time, he discovered the excitement and reality of novels. In the great novelists, he found storytellers who considered concepts, developed narratives of alternative future states, and the power of story which stirred profound emotion. Ken drifted away from his attachment to archaeology and museums anchored in the past.

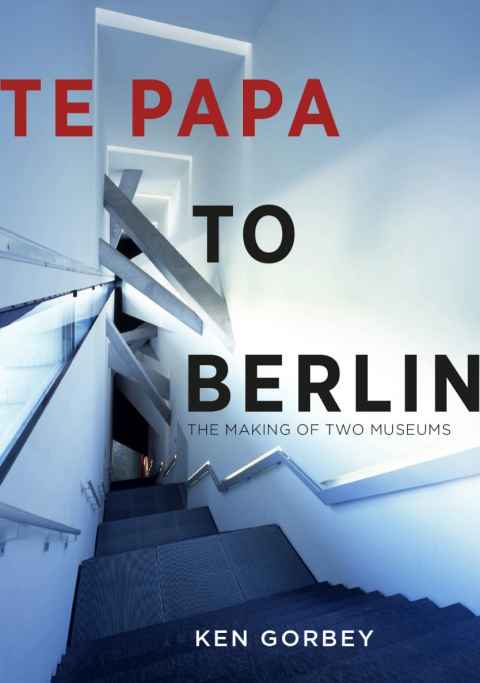

Ken is most well known for his legacy as a cultural champion spearheading two museums on either side of the globe. He spent 15 years bringing Te Papa Tongarewa to life, achieving cultural experiences renowned for being “bicultural, scholarly, innovative and fun”.

Te Papa is often credited in museological debate as a place thrown open to an ever-widening span of cultural perspectives. Later, he was shoulder-tapped to “rescue” a political hot potato, the imperilled Jewish Museum Berlin.

“Everyone expected it to fail, be boring, but it went on to be the most visited, and acclaimed as the most friendly museum in Germany.”

Surprisingly, Ken is equally proud of a much lesser-known project. Commissioned by Major Projects Victoria, he was tasked with bringing life to the Melbourne-fringing city of Geelong. Everyone expected a museum, but Ken saw the need for a central public library.

“That was a great feeling of achievement – running about 800,000 visits per year.”

In fact, it is libraries and books where he sees the true renaissance of the humanities.

I am looking for a future that is somehow lighter. That will keep me going until I pop my clogs.

From Waikato, Te Papa and Berlin, Ken gained a reputation as a bulldozer, a ringmaster, a disrupter and a radical. He brought in these ideas of storytelling, magical theatre, and customer-facing institutions aimed at drawing in “the 60 percent of people who couldn’t give a stuff about museums and collections”.

It’s a complex area that challenges many of the fondly held fundamentals of international museology, like collecting for the future – “what, which future?”

For a long while, Ken has been concerned with equity and finding a way for museums to “abandon the threshold”. Now, more than ever, he is fixated on climate change.

“Our buildings are too big. Our air conditioning is environmentally demanding. We collect because we can. I am looking for a future that is somehow lighter. That will keep me going until I pop my clogs.”

Golden Graduates

This profile is of one of the University's Golden Graduates. Golden Graduates are those who graduated from the University of Auckland 50 or more years ago, along with graduates aged 70 and over.

It first appeared in the spring 2022 edition of Ingenio magazine.