We need to at least talk about mining, in our own backyard

5 August 2024

Opinion: Associate Professor Martin Brook argues that protesting the mining of the minerals necessary to transition to green energy is like having your cake, eating it, then shutting down the bakery

Most of us know that to reach our climate goals and reduce the burning of fossil fuels, we need to transition to green energy. This means that, as the United Nations explains, we will need to extract large volumes of critical minerals around the world such as lithium, nickel and cobalt to meet the Paris Agreement goals. If we want to live in the manner to which we’ve become accustomed, we at least need to talk about this.

Many of course would say otherwise, as seen in demonstrations by environmental activists at the Victoria University of Wellington careers expo on July 25, which led to the Australasian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy and Rio Tinto’s booths being removed. The demonstrators created an intimidating atmosphere. It was such a pity for those involved, including those who’d given up their time to talk to university students about possible careers in mining, and students who were prevented from talking to people from the institute and Rio Tinto about possible careers.

Mining employs a huge range of career pathways: engineers, environmental managers, geologists, computer scientists and so on.

It’s extremely difficult to have a mature conversation with an environmental activist who demands we reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and is anti-mining, but at the same time depends on and even flaunts the technology and energy that comes from the mining of minerals.

Indeed, not only were those protesters preaching to the converted, they were preaching to the very people involved in facilitating the conversion from fossil fuel energy to green energy. It’s as if the demonstrators weren’t aware of the current global mining priorities and the energy transition they’re facilitating.

Our healthcare technology and componentry also require mined products, including the spectacles with which many of us need to see properly, and the forms of transport, including bicycles, trains, buses and even shoes (unless they are wooden clogs).

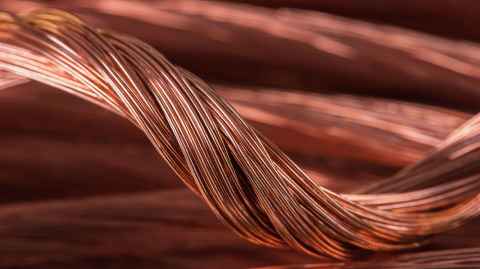

We all want to move to green energy and reduce dependence on fossil fuels, but to do that we need renewable energy, and will increasingly depend on that energy coming from windfarms or solar. Yet a single 3.2 MW wind turbine (not a large wind turbine these days) has 300 tonnes of steel (which is manufactured using coking coal) and five tonnes of copper, as well as aluminium. The energy is transported to us via other metals, and then we need a wide range of products in batteries to store the energy.

According to the International Energy Agency, the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy sources will depend on critical energy transition minerals, including copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt – just some of the essential components in many of today’s rapidly growing clean energy technologies.

The consumption of these minerals could increase six-fold by 2050. To meet the Paris Agreement goals, more than three billion tonnes of energy transition minerals and metals is needed to deploy wind, solar and energy storage. As the International Energy Agency has said, that data points to a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realising those ambitions.

The agency report provides six key recommendations for policy-makers to foster stable supplies of critical minerals, including that governments must give “clear signals about how they plan to turn their climate pledges into action”.

We need minerals for energy, we also need them for our technology. Everything from a soup spoon to a smartphone, and every piece of technology in between, depends on minerals that come out of the ground. Plastics are derived from oil. Crockery comes from a china clay quarry.

Our healthcare technology and componentry also require mined products, including the spectacles with which many of us need to see properly, and the forms of transport, including bicycles, trains, buses and even shoes (unless they are wooden clogs). We use mined materials to brush our teeth – the fluoride, sodium lauryl sulphate, calcium and carbonate in our toothpaste.

The disruption at the recent Victoria University careers expo episode exemplifies the cognitive dissonance shown by these activists; undermining people’s law-abiding civil liberties, while walking around with a smartphone and consuming everyday products and technologies that are comprised of mined minerals.

What we need in Aotearoa is a mature conversation about the extractive industry and how much it benefits us. Those who object to mining might have a point, but they (and probably most of us) could get better educated on this topic. ‘Geoscience for the Future’ and ‘Minerals in a Smartphone’ posters are available on the Geological Society of London’s website , which provide basic insights into minerals, technology and energy. Further very useful information is provided by Greenpeace.

From where I’m sitting, the environmental activists at Victoria University don’t walk their talk, practice what they preach, or put their money where their mouths are. What is truly most loathsome is that hundreds of thousands of people put their lives on the line every day working in mines around the planet to extract the raw materials that are used in the manufacturing of technology and products we use every day of our lives, consuming the fruits of other countries’ mining activities.

The (mining) train has left the station and it’s rapidly whizzing toward facilitating our transition to green energy and associated technological innovations, leaving fossil fuels largely in the past.

The fundamental question for Aotearoa is this: should we expect other countries to extract their raw materials, damaging their environments, to provide the technology that we demand, while imagining ourselves ‘clean and green’? Or should we ‘take one for the team’, and extract what minerals we reasonably can here, and feed these critical minerals into global supply chains?

We are a contradictory species. Like a lunchtime drinker in a bar bemoaning Aotearoa’s low economic productivity rates, I suspect many of those who have an automatic objection to mining, might like to reflect on the metals on their own person, such as silver and gold, that could well have remained in the ground.

I challenge these activists to get up with the play. It might have been useful to demonstrate opposition to mining 10 or 20 years ago, but the (mining) train has left the station and it’s rapidly whizzing toward facilitating our transition to green energy and associated technological innovations, leaving fossil fuels largely in the past. Mining companies and reputable organisations like the Australasian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy should be lauded for the energy transition they help facilitate.

The Government’s proposed minerals strategy closed for consultation on July 13, 2024 and the Government’s response to submissions will be intriguing.

Associate Professor Martin Brook is a chartered geologist and director of the Master of Engineering Geology degree, School of Environment, Faculty of Science.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland.

This article was first published on Newsroom, If you’re going to protest, at least walk the talk, 5 August, 2024

Media contact

Margo White I Research communications editor

Mob 021 926 408

Email margo.white@auckland.ac.nz