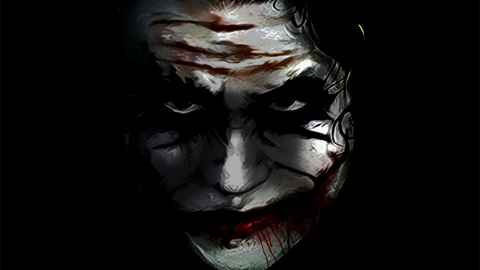

Joker a study in cruelty and whiteness

16 October 2019

Opinion: Acts of cruelty run through the film ‘Joker’, writes Neal Curtis. Some are explicit, others less so, but all leave an unsettling after-effect.

Joker is a fascinating character study of abuse, mental health and a world indifferent to both. The performance from Joaquin Phoenix is superb, and the pacing of the film by director Todd Phillips is excellent. The slow reveal of Arthur Fleck's biography, carefully punctuated by scenes of escalating violence is handled with great dexterity. In the end, it is hard not to understand that Joker is our creation, a construction of our society's precarity, violence and lack of care.

The cruelty in the film is summed up in Frank Sinatra's rendition of 'That's Life', where the pleasure other people get from seeing others fail is central; but cruelty can also be found in the song's disconcerting ambiguity. Against the backdrop of Arthur's mental illness, which resulted from pronounced abuse as a child and the ensuing social and economic marginalisation as an adult, the song rather callously tells him "to pick [himself] up and get back in the race". Arthur does this, repeatedly, until he can't do so anymore; or rather, until he takes a different - and especially violent - approach to picking himself up and getting back in.

So, what is interesting about a film centred on DC's #1 psychopath is that the cruelty in the film doesn't emanate from Arthur/Joker but from the attitudes of wider society. That said, Joker, as a film, contains its own cruelty, and this is where I have problems with what is otherwise a compelling piece of cinema. The cruelty of the film takes three forms; one pertaining to a specific moment of disturbing scopophilia, another relating to its general nihilistic message, the third relating to whiteness.

The indifference and spite of billionaires makes for an interesting political subtext, especially in an age that has seen an increasingly contemptuous oligarchy separate itself from and divest itself of any responsibility for the ills of wider society.

The first moment is the death of Randall (played by Glenn Fleshler), who also represents the collective responsibility for Joker's violence. In an attempt to get him sacked he gives Arthur the gun he later uses to kill three Wall Street suits on the Subway. After the incident, Barry and another of Arthur's colleagues, Gary, a man with dwarfism, visit Arthur to tell him the police are asking questions. Now knowing Randall had given him the gun only to set him up, Arthur summarily kills him in front of the traumatised Gary. There is no cruelty here, only swift and extremely violent death.

However, the cruelty in this scene stems from the director's decision to have Arthur put the chain back on the door when he first lets his colleagues into his apartment. As a result, when Arthur tells a terrified Gary he can leave he actually can't because he's unable to reach the chain to open the door. It is unclear what this part of the scene is supposed to do apart from give the audience a chance to cruelly laugh at a person with dwarfism, which in the packed theatre I was sat in, many people did.

The second aspect of the film's cruelty comes from its nihilistic and hopeless view of politics. The fulcrum for this is the killing of the banking trio on the subway. They are shown harassing a lone woman and then picking on Arthur, whose anxiety has triggered his neurological condition that makes him laugh uncontrollably. They proceed to beat him up, only for Arthur to take the gun given to him by Randall and kill all three. We soon learn these were employees of Thomas Wayne, Bruce Wayne's father, who praises them as good men while swiftly denouncing those celebrating the murders as envious, saying those who are not materially successful like him are just losers and clowns.

We are not just asked to understand the violence Arthur finally enacts as Joker, but are also expected to understand the justified violence of a white man when the protests of black men and women in the US are regularly met with condemnation, vilification and exclusion.

Here, the indifference and spite of billionaires makes for an interesting political subtext, especially in an age that has seen an increasingly contemptuous oligarchy separate itself from and divest itself of any responsibility for the ills of wider society. This is made clear in Arthur's next visit to his social worker, where he is told the programme has been ended as a result of the funding being cut; but the cruelty of the film is in its own representation of political opposition to this state of affairs, which is shown to be nothing but the dumb and chaotic violence of an enraged crowd adopting the clown mask as their symbol.

This is an eerie reworking of the political message of Christopher Nolan's third, extremely poor, Batman film, The Dark Knight Rises, where a popular uprising against oligarchy is represented as inherently stupid and tyrannical. Again, to take a positive view of this, we might read it is a critique of widespread right-wing populism where, in the words of neo-Nazi Andrew Anglin: "the mob is the movement", but it felt more like a sneering condemnation of popular politics and a cruel laugh at our seeming inability to meaningfully counter growing inequity.

The third aspect to the cruelty of the film is less explicit, but still leaves an unsettling after-effect. Throughout the film there are a number of black women who either don't properly listen to Arthur, chastise him, or fail to fulfil his sexual fantasy. In the fourth instance, a black woman becomes the face of his incarceration. We are led to believe he kills her when he walks bloodied footprints down the pristine white corridor of Arkham Hospital immediately after his first interview with her.

As an Englishman living in New Zealand I am perhaps insufficiently sensitive to the nuances of race in the US to comment on what these relations with black women tell us. However, one thing is very clear, even to me. We are not just asked to understand the violence Arthur finally enacts as Joker, but are also expected to understand the justified violence of a white man when the protests of black men and women in the US are regularly met with condemnation, vilification and exclusion. This seems to be the film's final act of cruelty.

Dr Neal Curtis is Associate Professor of Media and Communication in the Faculty of Arts.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Joker a study in cruelty and whiteness 16 October 2019.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz