Save antibiotics for serious infection - and future generations

16 January 2020

Opinion: Antibiotic use in NZ is high. This must be reduced, writes Mark Thomas, but at the same time balanced against health needs of specific communities.

The spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria is a steadily growing threat to the health of New Zealanders. Increasing antibiotic resistance will gradually reduce the ability of doctors to cure many infections such as pneumonia, skin abscesses, kidney infections and meningitis.

The epidemic of antibiotic resistance in New Zealand is, in many respects, like the epidemics of measles that have recently occurred here, in Samoa and in many other nations. The speed at which these epidemics grew, and the number of people who eventually suffered from the disease, was predominantly the consequence of how much close contact occurred between people, and the proportion of people who were already immune to the disease as the result of prior infection or vaccination.

The epidemics grew more rapidly and affected much larger numbers of people, in particularly crowded communities and in communities with lower rates of prior disease or vaccination.

Similarly, the epidemic of antibiotic resistance grows more rapidly in crowded communities, and in communities with high rates of antibiotic treatment. It will be especially threatening for people living in crowded situations where antibiotics are commonly used, such as hospitals and rest homes, because antibiotic use markedly increases the concentration of antibiotic resistant bacteria within the intestines and on the skin, and crowding markedly increases the spread of skin and intestinal bacteria from one person to another.

The most important strategies to reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance are to reduce crowding, improve personal and environmental hygiene, and avoid unnecessary antibiotic treatment.

Reducing crowding, and improving personal and environmental hygiene, will depend in large part on reducing poverty and enhancing the quality of housing and health literacy. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic treatment is a potentially simpler societal change. It “merely” requires that people less frequently seek antibiotic “treatment” for minor coughs and colds, and that doctors less frequently prescribe antibiotic “treatment” for patients who seek help for these illnesses.

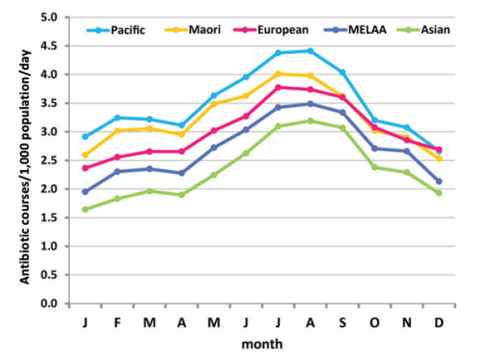

Unfortunately, it has been very common for people with coughs and colds in New Zealand to be treated with antibiotics. The high rate of prescribing of antibiotics for patients with coughs or colds is clearly illustrated by the marked increase in the number of courses of antibiotics dispensed daily per 1,000 population between May and September by pharmacies throughout New Zealand.

However, prescribing of antibiotics for winter coughs and colds is not the only way in which antibiotics have been overused in New Zealand. The annual rate of antibiotic dispensing in New Zealand in recent years, 3.0 antibiotic courses dispensed per 1,000 population per day during 2015, has been much higher than the number of antibiotic courses dispensed per 1,000 population per day in Sweden (0.9), Denmark (1.5), Canada (1.8), England (2.0) or the US (2.3). Relative to most other developed nations we have consistently overused antibiotics for very many years. While the bulk of this overuse has been for people with winter coughs and colds, we have also overused antibiotics for skin infections, and other common minor infections.

Fortunately, the behaviour of people unwell with a cough or a cold, and the behaviour of the doctors they consult, has changed significantly in New Zealand in recent years. The number of antibiotic courses dispensed per head of population has fallen by about five percent each year since 2015. Experience from other countries suggests that such reductions in the rate of antibiotic treatment are not associated with an increase in severe infectious diseases.

However, there are good reasons to be cautious. Māori and Pacific people suffer more frequently from many infections that do require antibiotic treatment, such as pneumonia, skin infections, and rheumatic fever (as the occasional consequence of a sore throat caused by Streptococcus pyogenes). Therefore Māori and Pacific people should receive antibiotic treatments more frequently than Pākehā, Asian or other New Zealanders. However, Māori and Pacific people also are prescribed antibiotic treatments that provide them with no benefit. The winter increase in antibiotic prescribing for coughs and colds is just as marked in Māori and Pacific people as it is in people of other ethnicities.

Increased public understanding of what illnesses do need antibiotic treatment, and what illnesses will not be benefited by antibiotic treatment, will help people to decide whether to consult a doctor or merely stay home and rest. Improved patient care by doctors – promptly prescribing antibiotics for illnesses that do need antibiotic treatment, and consistently declining to prescribe antibiotics for illnesses that will not benefit from antibiotic treatment, will reinforce public understanding.

Antibiotics should be regarded as precious medicines that can provide great benefit in the treatment of many severe bacterial infections, but which can be wastefully squandered by the “treatment” of coughs and colds and other illnesses for which they actually confer no benefit.

All antibiotic use helps to increase the rate of antibiotic resistance. We should refuse to take antibiotics when there is no realistic expectation of them giving any benefit. Our children and grandchildren will appreciate our wisdom if we do not bequeath to them a large number of bacteria that we have made resistant by wasteful use of our currently very effective antibiotics.

Dr Mark Thomas is an Associate Professor in the Department of Molecular Medicine and Pathology.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Save antibiotics for serious infection - and future generations 16 January 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz