A close look at the superannuation problem

20 February 2020

Opinion: The pressures on the state budget of a rapidly ageing population must be acknowledged and treated holistically, write Susan St John and Claire Dale.

The latest three-yearly 2019 Retirement Incomes Review takes a refreshingly holistic view of retirement policy and is welcomed by the Retirement Policy and Research Centre at the University of Auckland. Interim Retirement Commissioner Peter Cordtz has followed signals given in the Terms of Reference that reflect this Government’s wellbeing approach.

This broader scope has enabled, for example, a move away from the simplistic mantra that the retirement age should rise to 67. Instead, the review allows for a nuanced assessment of wide costs and benefits if the pre-retirement group is expected to be self-supporting for two more years.

Clearly, today's longer life expectancies may not be enjoyed by a sizeable group who have experienced an adverse trajectory of life experiences. Many future retirees will be much less well-prepared than baby boomers. Redundancy, unemployment or sickness can cripple retirement plans for those approaching retirement, as can lack of home ownership or high mortgages at the point of retirement. For those who need to spend an extended period of time on a welfare benefit such as the Supported Living Payment, the prospects of a comfortable retirement can quickly disappear.

While most of those aged 50-64 years are employed in paid work, around 150,000 are supported by state payment. More than half of those on a benefit have been on it for more than five years, and two-thirds are on a benefit because of health disability. These figures provide a snap-shot at a point in time, but the probability of a person needing a benefit, ACC or supplementary assistance at some time between the ages of 50 and 65 is much higher. In later working age, periods of unemployment, redundancy, ill health or caregiving duties may impact severely on the ability to prepare financially for retirement.

Nevertheless, the pressures on the state budget of a rapidly ageing population must be acknowledged. The RPRC agrees that while not increasing the qualifying age for NZ Superannuation (NZS) is sensible, the fiscal problems are real - as is the underlying intergenerational conflict for scarce resources.

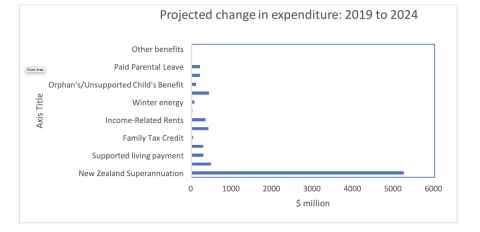

The Treasury’s budgetary figures show dramatic increases in spending on pensions and healthcare. Looking just at pensions, the graph shows how the projected four-yearly increase in expenditure on NZS dwarfs spending increases on other transfers.

Last year, NZS cost $14.5 billion. By 2024 it is projected to cost nearly $20 billion a year.

In the RPRCs contribution to the review: Intergenerational impacts: the sustainability of New Zealand Superannuation, we argue that a holistic approach must be taken to government spending rather than a narrow focus on whether NZS is sustainable or affordable. A proportion of NZS goes to very high-income/high-wealth superannuitants. Universal payments to those who do not need it can be legitimately questioned, especially when the top tax rate is low as it is in New Zealand. If societal well-being is the aim, a better use of the money might be addressing widespread social distress, homelessness and family poverty.

If unnecessary spending on NZ Super indeed is the ‘problem’, then raising the age is clearly not the answer. Lead-in times of up to 20 years have been proposed so that raising the age will not generate any saving for a very long time. Moreover, there will be offsets because many aged 65-67 will struggle and need government support.

There would be justifiably grave concerns if reducing the rates of NZS were to be used as a source of saving, although over time, alignment of the single sharing rate and the married person rate is needed. That leaves introducing some kind of clawback income test.

The RPRC suggested a universal tax-free grant at age 65 paid at the net rate of NZS, with a claw back for those with large amounts of extra income.

The clawback would be simple to operate as described in the RPRC report and not have any of the stigma of a means test. It can be designed to have little or no effect on the vast majority of superannuitants. Income would be taxed on a separate, progressive scale, so that after a cut out point at a high income, the effect would be that there was no advantage to having the grant.

At age 65 a choice could be made either to go on the grant and have income taxed on the separate tax rate, or not to access the grant. The grant would still be universally available to all, and any overpayment of tax could be refunded at the end of the year. Just as now the basic income would facilitate part-time employment of those over 65 as well as much social usefully unpaid work.

While Treasury does not endorse this or any other policy, their costings show under various scenarios it is possible to save at least 10 percent of the annual cost of NZ Super by gradually removing it from high income people who would barely notice.

The RPRC welcomes more debate on this issue and agrees with Peter Cordtz when he said the incoming Retirement Commissioner was best placed to lead these debates.

Susan St John is Associate Professor of Economics and Dr Claire Dale is a research fellow at the Auckland Business School.

This article reflects the opinion of the authors and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom A close look at the superannuation problem 20 February 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz