Were post-pandemic cities best planned 100 years ago?

19 May 2020

Opinion: A housing project designed 100 years ago by Frank Lloyd Wright could provide a blueprint for a post-Covid change in urban vitaility, explains Diane Brand.

One hundred years ago, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright began to design a settlement called Broadacre City during a period where he had few architectural commissions.

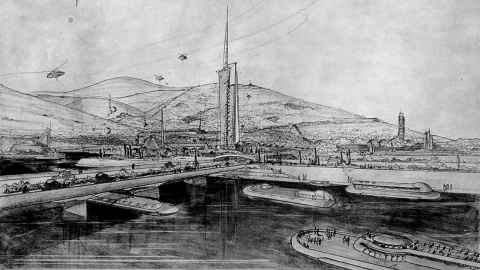

The proposal held up a mirror to dense conurbations (skyscraper cities) such as Chicago and New York. It offered the US an alternative urban vision of the future, presented at the 1935 Industrial Arts Exhibition, ironically hosted in the towering Rockefeller Centre, New York. Wright’s project was further articulated over the remaining years of his stellar international career, but it remains the project he is least remembered for.

As we endure the global Covid-19 pandemic, the concept is worth revisiting for its foresight.

Broadacre City was designed as a flat super-grid of family homesteads of one acre and above, translating into an overall density of 2.5 people per acre. (In 2010 Manhattan had a density of 108.5 people per acre). Factories were located under sweeping motorway infrastructure, transportation was by driverless vehicles and helicopter-like flying machines, and connection to the world was via yet-to-be invented technologies such as the internet.

The concept followed on from late 19th century planning movements designed to tame the evils of the dense cities that had emerged from the Industrial Revolution, such as inequality, poverty, disease, crime and exploitation.The result was the City Beautiful Movement in America and the Garden City Movement in Britain, both of which ultimately influenced the growth of suburbia on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond.

Such schemes favoured a low-density city of predominantly single-family dwellings connected by public transport networks or highways. The New Zealand city has embodied these characteristics for a major part of its history. Critical to Wright’s scheme was the concept of a democratic city of equal disposition where the dwelling and workplace were integrated on an ample land parcel, with an economy and society that was composed of ‘small farms’ and ‘small industries’, reviving Thomas Jefferson’s founding and spatially generous ideal of ‘democratic society’ in the United States.

Suburban living has proven to be an advantage during the current Covid-19 crisis. Families or households were able to retreat into ‘bubbles’ and streets emptied of vehicles, allowing the prescribed levels of physical distancing at Level 4 lockdown.

For affluent households with larger dwellings, it facilitated working from home, with gardens allowing for individualised open space or growing household produce. Technology has enabled work to continue in this location where there is space to accommodate it – and also when there is not, as workers Zoom from cars, garages, garden sheds and walk-in wardrobes. With driverless cars and drone delivery still the exception rather than the rule, couriers carefully deposit groceries and online purchases and quickly retreat. We are now temporarily living in a quarter-scale version of Wright’s dream with the technologies he envisioned on the brink of popularisation.

Broadacre City was labelled an ‘anti-city’ by some urbanists, because of its dilution of people and its flattened and distributed community and public places. The super concentration of diversity, culture, art, politics, commerce and life were aspects of urban life that captured the hearts of New Yorkers and Bostonians alike and propelled these types of cities into the popular imagination.

Wright focused on creating a city that was immunised from the associated inequalities of the great metropolis, and he instead promoted the very American private world of the ‘bubble ’and the freedoms and opportunities of the individual. Public space consisted of expansive boulevards and dispersed public buildings that you might now encounter in Brasilia Chandigarh or Canberra. No Times Squares throbbing with neon, traffic and panhandlers here.

However, density is not really the central issue here as we have seen catastrophic contagion in low-density regional Italy and minimal infection rates in high density Taipei. It is the broader economic and social consequences of the pandemic that will shape our future cities more fully than the conceptual thinking of built environment theorists. In post-Covid New Zealand we may risk losing the vitality associated with the ‘city’ as a result of changes aimed at minimising transactional and interactive human behaviours.

Will retail contraction resulting from business failure or recession strip our streets and public places of activity and surveillance? Will our downtowns and commercial centres shrink as a higher percentage of organisations embrace working from home as business as usual? Will our large public buildings and icons of culture such as town halls, art galleries and concert halls be mothballed as a fear of crowds becomes a survival reflex? Will supermarkets and restaurants resort to click and collect or home delivery rather than maintain their main street premises? Will large chunks of learning move online, taking the public presence and amenity of education with them? Will faith be virtual leaving religious buildings bereft of congregations, empty symbols of a moral guidance?

All of the above are possible in some distorted version of our future and some changes will be highly probable. Each loss of normal function in our cities and towns will present us with a depletion of an already skeleton public realm that may erode a fragile urban culture and traditional sense of community. Our public realm and collective sense of urban culture and vitality is certainly going to change.

Professor Diane Brand is Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Were post-pandemic cities best planned 100 years ago? 19 May 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz