The truth is not set in stone

16 June 2020

Opinion: Ancestors of present-day New Zealanders fought on both sides during the New Zealand Wars. And both sides should be remembered, writes Avril Bell.

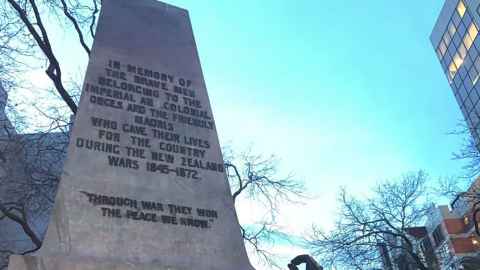

There is one particular colonial monument that really bugs me, mainly because I pass it every time I bus into central Auckland to work. It’s a monument to ‘the brave men belonging to the imperial and colonial forces and the friendly Maoris (sic) who gave their lives for the country during the New Zealand Wars, 1845-1872’.

And at the base of the inscription is the quote: ‘Through war they won the peace we know.’ Where to start? Peace for some was devastation, injustice and dispossession for others. And why are we not remembering the Māori warriors who fought on the other side of these wars in defence of their families and homes?

This monument stands on the intersection of Symonds and Wakefield Streets in central Auckland, passed by thousands of people every day. I’m clearly not the only person who is bothered by it, as it was tarred and feathered and pulled off its base before the head was cut off the figure of Zealandia during the 1981 anti-Springbok Tour protests.

Then in 2016, Zealandia’s palm frond and flag were broken off and in 2018, anti-colonial and anti-racist protestors embedded an axe in her forehead and left a poster in front of the monument saying ‘Fascism and white supremacy are not welcome here’.

So we could argue that it’s serving a useful function as a focal point for political expression and protest. And it’s notable that Auckland Council (both pre- and post- Super City versions) has stubbornly refused to remove or modify this or other colonial-era monuments, such as that memorialising Colonel Marmaduke Nixon whose troops set fire to the church at Rangiaōwhia during the Waikato War, killing people sheltering inside.

But I think it’s timely, or past time, that something be done about these unabashedly colonial memorials. As Vincent O’Malley says, history changes. We revise the historical interpretations of the past to reflect the concerns of the present. As society changes, so do our historical accounts. History is political and so too are monuments. They are established in celebration of the political status quo at the time of their erection (1920 in the case of the central Auckland memorial).

And as Claudine van Hensbergen has recently argued in response to the toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, UK, ongoing political engagement with these monuments is appropriate. Given the political motivations behind their creation, it is natural, she says, that they invite a political response. Such responses, she argues, should be welcomed as a sign of the ongoing relevance of the issues being memorialised.

In terms of the war memorial in central Auckland, the idea of ‘constitutive forgetting’ developed by social memory theorist Paul Connerton is helpful. In this memorial, the suffering and losses of Māori who fought against colonial forces in the New Zealand wars are effectively forgotten; and they are forgotten precisely to create, or constitute, something new.

This is a particular kind of forgetting that supports the creation of a new identity, in this case a Pākehā-centric national New Zealand identity. Forgetting the other side of these wars allowed our early 20th-century Pākehā ancestors to create historical stories of their own peace-loving, moral character, feeding the mythology of ‘the best race relations in the world’; and here’s where remembering the ‘friendly Maoris’ who fought alongside them is important.

Even more fundamentally, this selective forgetting allowed them to create stories of themselves as New Zealanders (not colonising migrants) by forgetting the violence by which they acquired this identity.

But these were civil (uncivil?) wars. Ancestors of present-day New Zealanders fought on both sides of these wars. And both sides should be remembered if we want to move away from Pākehā-centric, or Pākehā-only, accounts of who we are as a nation.

...this selective forgetting allowed them to create stories of themselves as New Zealanders (not colonising migrants) by forgetting the violence by which they acquired this identity.

It’s time for some constitutive remembering to honour all sides of our national history, time to ‘get curious’ about our history, as Amanda Thomas says. And time then, also, to have a conversation about how and what to remember.

Claudine van Hensbergen suggests outdated monuments could be relocated within museums where their stories can be retold and recontextualised to continue their work of public education. Or that new monuments or sculptures could be commissioned, in our case from Māori artists, to either replace or stand alongside them.

Personally I like possibilities that keep these troubling historical monuments in some form, either in the museum or in our parks, but retells their stories in light of what we are now ready to face about our painful past. However, it’s not my decision. In terms of decision-making on the what and the how, I’m with Vincent O’Malley. These processes must be led by iwi and hapū whose ancestors’ lives are being remembered and forgotten in the present memorials.

Dr Avril Bell is an associate professor in sociology in the Faculty of Arts.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom The truth is not set in stone 16 June 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz