Will US election be a geopolitical turning point?

13 July 2020

Opinion: Stephen Hoadley on how Donald Trump has moved the US from its role of international leadership which might not be easy for a President Biden to restore.

US elections and the resulting presidencies can be geopolitical turning points, whether reflecting them or causing them. Successive presidents since William McKinley moved the US from an introverted, post-civil war frontier nation to an international leader.

And then came Donald Trump’s election in 2016.

Until Trump’s digressions, US presidents had made the following contributions to ‘making America great’:

William McKinley 1896-1900 annexed Hawaii, precipitated the Spanish American War that liberated Cuba from Spain and secured Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines for the US, and set the US on a path to power in the Pacific and Asia.

Theodore Roosevelt 1900-1908 built a modern US Navy and sent it, ‘the Great White Fleet’, around the world in 1908-9, asserted US primacy in Latin America against European creditors, saying ‘Speak softly but carry a big stick’, supported Panamanian independence from Colombia and helped build the Panama Canal, negotiated a Russo-Japan treaty and won a Nobel Peace Prize.

Woodrow Wilson 1912-1919 sent troops to help Britain and France defeat Germany in WWI, proclaimed the ‘Fourteen Points’ of a liberal world order of states independent of colonialism, played a major role in post-war negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles and the creation of the League of Nations, and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

Franklin D Roosevelt 1932-1944 was an internationalist former Secretary of the Navy but was hampered by Congress’s Neutrality Acts. Nevertheless, he clandestinely aided Britain against Nazi aggression, proclaimed the ‘Four Freedoms’, opposed European colonialism, led US to victory over Germany and Japan, negotiated post-WWII agreements with Churchill and Stalin, and lobbied skilfully to gain Republican Party and public support for a new United Nations.

Harry S Truman 1944-1952 decided to drop two atomic bombs on Japan, presided over democratisation and economic rehabilitation of Japan and Germany, presided over establishment of the United Nations, confronted Soviet encroachment in Middle East and Southern Europe, sent troops to save South Korea from North Korea, Initiated international economic aid ‘Marshall Plan’ and ‘Point Four’, rationalised the US military establishment and deployments, developed the ‘containment doctrine’ to restrain the USSR, and negotiated defensive alliances with NATO, Japan, S Korea, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand, supported UN and international organisations such as WHO, and began global trade liberalisation through GATT (predecessor of the WTO).

Richard M Nixon 1968-1973 accelerated bombing of North Vietnam & Laos, then with Kissinger negotiated a peace agreement in 1972 and US withdrawal from South Vietnam, led a rapprochement with China to isolate the USSR, initiated ‘detente’ with USSR and negotiated the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty.

Ronald Reagan 1980-1988 negotiated release of US hostages in Iran, intervened in the Nicaraguan civil war, the Afghan civil war, the Grenada conflict, and the Panama dictatorship. He negotiated nuclear arms control agreements with Gorbachev, notably the Intermediate Nuclear Forces deal to remove nuclear missiles from Europe. He also initiated the Strategic Defence Initiative (ballistic missile interception) and set the stage for the later collapse of the USSR.

George W Bush 2000-2008 initiated a divisive War on Terror and the Guantanamo prison, intervened in the Afghan civil war against the Taliban, invaded Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, antagonised and divided traditional allies, withdrew from ABM Treaty, criticised the UN and withdrew from UN agencies. But he also increased aid to fight HIV/AIDS and malaria in Africa.

Barack Obama 2008-2016 resumed cooperation with international agencies, repaired relations with traditional allies, won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, helped Iraq defeat ISIS and the Kabul government to resist the Taliban. With the P-5 and Germany he negotiated a nuclear restraint deal with Iran (JCPOA) and signed New Start nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia. To balance China he initiated the US ‘Rebalance [‘Pivot’] to Asia’ and joined the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade talks.

To sum up, under presidents from McKinley to Obama the US became the:

· Richest economy and most valuable trader in the world.

· Most effective military (although China’s is larger).

· Widest global diplomatic presence.

· Largest aid donor and human rights advocate.

· Participant in all important international organisations.

· Party to hundreds of bilateral and multilateral treaties.

· Leading projector of ‘soft power’, innovation, and science.

· Leader in trade and investment liberalisation negotiations.

· Preferred destination of most migrants and refugees.

· Provider of global ‘hegemonic stability.’

· Advocate of a ‘rules-based world order.’

In contrast to his predecessors, what marks Donald Trump’s presidency?

· Personal outreach to autocrats Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Kim Jong-un, Rodrigo Duterte, Jair Bolsonaro, Andrzej Duda, Narendra Modi, Mohammed bin Salman, Hashim Thaçi.

· Disrespect for traditional allies Canada, France, Germany, NATO, Mexico.

· Withdrawal from or rhetorical undermining of UN agencies, UNHRC, WHO, WTO, and the Paris Climate Conference.

· Withdrawal from the INF Treaty and Open Skies agreements and reluctance to renew the New Start treaty.

· Reduction of budgets for aid, diplomacy, and human rights advocacy.

· Budget increases for military, especially nuclear and missile forces, while pulling out US forces from the Middle East.

· Disdain of trade agreements and imposition of arbitrary tariffs on China, Europe, Canada.

· Blatant ‘America First’ policies discrediting US global leadership.

But what’s wrong with an ‘America First’ policy? After all, every government puts its own interests and people first, so why not the US? To ask it another way, why should the US pay for world stability? The answers are several, as follows:

· US neutrality in the 1930s allowed the aggressors Germany, Italy, and Japan to trample over their neighbours.

· Global stability and liberalising trade have made possible rising standards of living almost everywhere as well as in the US.

· Institutions and rules are good for US manufacturing, commerce, and consumption…and for most other economies, too.

· Less scrupulous and more ambitious autocracies (China, Russia, Iran, North Korea) are poised to fill vacuums of power vacated by the US.

· Well-meaning democracies are too small and dispersed to resist the challenges of anti-democratic forces, so need US leadership.

If one subscribes to the aphorism that ‘Great power entails great responsibility’, then it is incumbent on the hegemon, the US since 1945, to promote international stability and cooperation which helps others at the same time as it helps itself.

Trump appears to be deviating from prior presidents by undermining international stability and cooperation and displaying global (not to mention domestic) disregard bordering on irresponsibility.

Can a Biden presidency turn the US back to its prior internationalist geopolitical course? By his supporters Biden is sometimes described as a ‘restorationist’ who in his foreign policies would:

· Return to US core foreign policy principles.

· Build on Obama’s moderation but adapt them to new circumstances.

· Re-join international organisations and arms control treaties.

· Reaffirm alliances, diplomacy, and aid.

· Pursue trade liberalisation…but cautiously.

· Adopt climate change policies.

· Rally democratic states against dictatorships.

· Stand firm against China and Russia.

But can Biden win the presidency in November? The signs are hopeful for the Biden team. Biden is 10 percentage points ahead of Trump in an average of polls. He has been endorsed by Obama, Sanders, Powell, 80 top former security officials, several new Political Action Committees (PACs), and by the majority of persons of colour.

In contrast, Trump has abdicated leadership in coronavirus, race relations, and Russia issues and his Republican Party has deserted its mainstream principles to back Trump’s divisive electoral politics and partisan civil service and judicial appointments. Trump is losing support among women and educated suburban voters. Republican-led states have the worst coronavirus records and are re-entering lock-down.

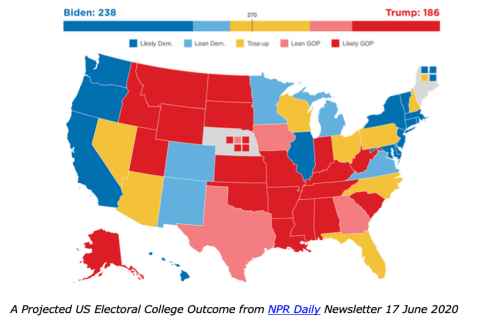

But a Biden win is not certain. Why? Recall that in 2016 Hilary Clinton was five percent plus ahead but lost. The US electorate is polarised into Red and Blue, and those in the middle are cross-pressured, confused or angry about the coronavirus lockdowns, and thus unpredictable. More Republicans than Democrats turn out on election day and they are intensely loyal to Trump, who is exciting in contrast to Biden’s relative blandness. Finally, the arithmetic of the Electoral College favours Trump.

The US Electoral College is not a transparent ‘proportional representation’ system but a gerrymandered (politically distorted) multiple single-member-constituency ‘winner take all’ system. Gore in 2000 and Clinton in 2016 won clear popular majorities but lost in the convoluted Electoral College tally.

Nevertheless, the Democrats are optimistic. This illustrates why:

Let me offer a final note of caution: A Biden win may not produce quick changes in US foreign policy. This is because critics of globalism, free trade, and liberal immigration are growing and authoritarianism is spreading in Europe and Asia. Hostility to the US in China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, and elsewhere, too, will not be dispelled by a Biden presidency.

Biden is not a bold leader but a moderator. He will move cautiously, and will face a hostile GOP in Congress. Replacing Trump’s appointees with his own will take months. The US is a complex institutional system bounded by domestic and international laws, so policy, whether international or domestic, is difficult to implement quickly without breaking rules or laws, as Trump is alleged to have done.

Biden’s appeal lies in his respect for rules, laws and institutions. But ironically, these will constrain him as he attempts to get the ship of state back on course and restore American leadership after Trump’s digressions.

Stephen Hoadley is Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations in the Faculty of Arts.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Will US election be a geopolitical turning point? 13 July 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz