Fixing Auckland's water crisis

15 July 2020

Opinion: Can we avoid the angst and embarrassment of another water crisis in Auckland like the current one? Anthony Fowler takes a look.

In the midst of the Covid-19 lockdown, Auckland’s water reservoirs dropped to levels not seen for a generation. WaterCare dusted off the drought management plan and we came out of lockdown being urged to conserve water (but to keep washing our hands). There was no great alarm, but the possibility of significant issues next summer was flagged.

Then the political genie was let out of its bottle. A ‘water crisis’ was declared by the mayor, a crisis mantra took hold, and the blame game began. The shift from “keep calm and carry on” to “the sky is falling” was remarkably fast and, in my view, highlights inherent tension between water planning and water politics. I recall seeing this before – at the beginning of the 1994 water crisis.

Something clearly isn’t working here. But why? And if we can figure that out, can we find a solution that avoids the angst and embarrassment of it happening again?

How things are supposed to work

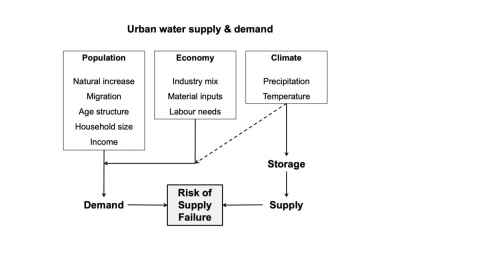

Urban water resource planning, most simply, is a balancing of demand and supply. Demand is determined by a mix of population and economic factors, with climate of only minor importance (for example, influencing summer garden watering). Supply is determined by climate and engineering. Storing water in reservoirs increases supply and makes it more reliable by capturing flood flows which are then used during dry periods. This happens both seasonally and between years.

For any configuration of demand and supply there is an associated risk of supply failure. Urban water supply systems are not normally designed with zero risk, because it is considered fiscally imprudent to do so. Instead, a level of risk is accepted that is cost effective. In crude terms, a decision is made to accept the risk of drought-related impacts because avoiding them would cost more in the long run.

Risk of supply failure is typically expressed in terms of a drought return period and is a political decision. Prior to the 1994 water crisis it was 1-in-50 years. Afterwards it was changed to 1-in-200 years to achieve a more resilient water supply system.

Why it has failed us

The risk-based approach makes sense, has a long history, and works well most of the time. By accepting risk, we delay infrastructure development and pay lower water bills. It fails though when a big drought finally arrives and calls our bluff. The water professionals then gird their loins and start actioning the agreed drought management plan, but the politicians quickly fold. They need to get fired up in order to make the management plan work, but that also fuels the public impression that there must have been a cockup and that heads should roll.

Good luck to any politician trying to argue that the anticipated economic impacts being highlighted by the media are just part of the accepted risk, especially when the benefits are history. Under these circumstances, political panic and seeking emergency solutions are to be expected. 1994 and 2020 are identical in this regard.

My argument here though is not that we should toughen up and reap what we have sown. Rather, we should accept that the planning approach is broken. Although politicians may be willing to sign up to a risk threshold, based on economic arguments, they are neither willing nor able to sell it when significant drought arrives.

A possible solution

The obvious solution in a crisis is to conserve water and to find additional summer supply to see us through. Auckland has a long history of doing this and the proposed increased take from the Waikato River is simply the latest example. But we should be careful not to fall into the trap of allowing an emergency response to automatically morph into the long-term solution. Doing so may pause, but won’t fix, the crisis dynamic.

An alternative is to focus on what actually triggers a political water crisis and to seek a more focused solution.

The 1994 and 2020 water crises were both called in winter. The critical trigger was low reservoir levels, which were seen (literally) as insufficient to see us safely through the following summer, should the drought continue. It may not of course (1994 didn’t, and who knows if 2020 will).

If reservoir levels are the key to political panic, perhaps they are also the key to a solution. Additional summer supply sources will certainly ease the pressure and allow reservoir levels to be maintained, but this is a temporary and arguably inefficient solution.

An alternative is to ensure that reservoir storage is sufficient ahead of the summer drawdown by supplementary pumping of river flood flows in winter and spring. This approach would allow the reservoirs to be used most efficiently, ensure that we don’t have to anticipate droughts that may never eventuate, and avoid embarrassing political panic.

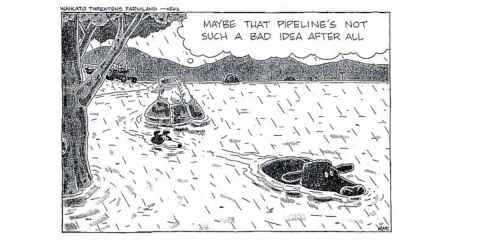

Exploiting river flood flows also has a couple of other big advantages. First, if it is the Waikato, it avoids competing use issues because nobody else wants the water, as nicely illustrated by the 1994 Klarc cartoon published after the drought broke. Second, it opens up multiple other potential water sources around the Auckland region.

Is it practicable? Clearly yes, because this was exactly what was proposed as Auckland’s next water supply option immediately prior to the 1994 crisis. Then, an emergency solution morphed into a long-term plan. And look where that has gotten us.

Associate Professor Anthony Fowler is from the School of Environment.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Fixing Auckland’s water crisis 15 July 2020.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz