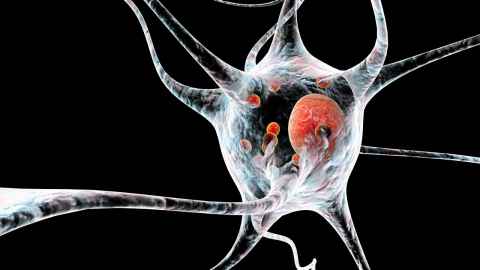

Researchers find key that may unlock Parkinson's Disease puzzle

24 August 2020

Liggins Institute scientists have decoded a gene that plays a major role in regulating and delaying the onset of Parkinson's disease.

Researchers from the Liggins Institute at the University of Auckland, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, and University of Otago have discovered that components of the gene GBA have a significant role in regulating and delaying the onset of Parkinson’s disease, the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the world.

The leading journal on Parkinson’s disease, Movement Disorders is highlighting the researchers’ new approach by featuring the team’s findings as the August cover story.

Associate Professor Justin O’Sullivan, who co-led the project, said, “We believe we have come up with a plausible understanding of how GBA contributes to the disease that opens new approaches to treating Parkinson’s and delaying its onset.”

Despite the number of people it affects, Parkinson’s remains a medical mystery. Doctors do not know why most people develop Parkinson’s and for those diagnosed, there is no cure.

The question we are asking is why do some people with GBA mutations develop Parkinson’s and others do not?

Dr O’Sullivan and his colleagues specialise in research into gene control. They decided to look closely at the gene GBA, which is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s, and has been used as a biomarker for the disease.

Dr O’Sullivan said:”The question we are asking is why do some people with GBA mutations develop Parkinson’s and others do not?”

Sophie Farrow, William Schierding and Oscar Graham looked for answers in the non-coding parts of the GBA gene that were once thought of as ‘junk DNA’. The tag ‘junk DNA’ has become a misnomer as it is now known that DNA sequences within it can act as switches that regulate the action of genes, amongst other things.

In the case of GBA, the team screened 128 sites in the non-coding part of the GBA gene. They found that if the GBA gene has a particular combination of three short non-coding DNA sequences, the result is a delay of the onset of Parkinson’s by five years.

They also identified six other non-coding regions that act as ‘switches’ to control how the GBA gene is turned on or off in the movement and cognitive centres of the brain, the substantia nigra and cortex. The team have created a map that shows how switches affect other genes – in addition to GBA – throughout the human body.

Therapy target

Associate Professor Antony Cooper, Research Director of the Australian Parkinson’s Mission, said: “We are working to discover the molecular basis of the delay in disease onset, which would provide a target for therapies to delay disease onset and disease progression in patients”

O’Sullivan said,”Traditionally Parkinson’s has been seen as a disease of the brain. We suggest that the regulation of GBA throughout the body is important in the development of the disease and that there is a network effect through how the switches control the GBA gene and other genes.”

The new information not only means there is a way to improve the screening of candidates for medical therapies, but it also opens up new ground to explore ways to prevent, delay and treat Parkinson’s, through gene and drug therapies.

Research that led to the approach to understand GBA’s role in Parkinson’s was funded by the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Silverstein Foundation for Parkinson’s with GBA.