Michele Leggott's tribute to Derek Challis, son of Robin Hyde

2 March 2021

Derek Challis, son of writer Robin Hyde, died in January 2021 aged 90. Professor Michele Leggott paid tribute to a man who overcame a tough start.

He opens a suitcase and there they are, the precious manuscript notebooks written by his poet mother Robin Hyde, born Iris Wilkinson. We are in Dunedin for a Hyde conference.

“Yes,” says Derek Arden Challis. “I put them in the boot and we drove down from Auckland.”

He’s enjoying the gasp of horror around the room full of Hyde aficionados (a suitcase, the boot, the distance between Te Henga and Dunedin, these unique manuscripts on the road with their legal owner and guardian). He wants to make us jump, as his mother, a legend, always wanted to make her listeners jump. It’s a literary tactic and Derek has inherited it in full.

The notebooks are of course safe and come to no greater harm than being enthusiastically riffled around the room of admiring scholars. We get over ourselves, but the moment is not forgotten. It’s linked with other moments in Derek Challis’s long history, one of them the trip he took to Ohakune as a 27-year-old biology technician to saw off the head of a circus elephant dead from tutu poisoning, and send it back to Auckland University’s Biology Museum.

Derek Challis was born in Picton on October 29, 1930. His delivery coincided with two significant earthquakes that Hyde liked to think showed promise for her boy. At the age of three weeks, he was smuggled aboard the ferry for Wellington in a dress basket, to keep his existence out of the world’s eye because solo motherhood and staff journalism were not compatible options in respectable New Zealand of the 1930s. The child was boarded in Palmerston North and then Auckland as Hyde endeavoured to work and support him.

She wrote a suite of poems (Derry’s Rhyme Book) for his fourth Christmas and her memoir, A Home in This World, outlines the difficulties of mothering at a distance. The poet mother and the political mother sometimes coalesced, and in 1938 Derek was exhorted to ask other children to gather and donate items for the struggling Chinese in their fight against Japanese aggression: “Do you think you’re too young to ask your schoolmates if they’ll start collecting some of the things I mentioned for the poor people of China – the refugees or the soldiers, whichever seem more easily helped – and maybe that would start other schools off all over New Zealand?”

When Hyde died in London in August 1939, Derek was eight years old and prospects were grim. The family with whom he had lived were no longer able to accommodate him, and Derek spent several years in an orphanage.

When Hyde died in London in August 1939, Derek was eight years old and prospects were grim.

The family with whom he had lived were no longer able to accommodate him, and Derek spent several years in an orphanage. He left school to join the navy and, after serving in Korea, left to pursue studies at the University of Auckland, working as a technician in the Zoology Department.

He lived in a bach at the Ellerslie home of Rosalie and Gloria Rawlinson, who had been close friends of his mother. The Rawlinsons were in possession of Hyde’s manuscripts and there was an agreement between Gloria and Derek in the 1960s to collaborate on a biography of Hyde, Gloria doing the writing, Derek assisting with research.

When Derek took a teaching job at Bay of Islands College in 1970, progress on the biography stalled and Gloria eventually shelved it as a completed draft. When Gloria died in 1995, Derek gained possession of the draft and decided to complete the biography with help from wife Lyn and some support from a Marsden grant.

This is where my direct knowledge of Derek enters the picture, though previously I was one among many who made the trip to the Challis home in the bush on Te Henga Road, to be given access to Hyde manuscripts and fed by the hospitable Challises. It wasn’t always easy. The tangled history of the papers, resting on the event of Hyde’s suicide in London, was always in view. Derek’s investment in them was bound up with the emotional break he suffered when his mother died, something that could never quite leave the room.

“She’s still here, you know,” he would say. “Right here.”

We all felt the presence, none more so than Derek.

The Book of Iris is, in the final analysis, a labour of intense love for its subject and needs to be read as part of the family romance Derek Challis inherited and made good.

When Derek and Lyn discovered late in the redrafting of the biography that Gloria had manufactured some of Hyde’s letters from wartime China, the fallout was immense. Derek had regarded Gloria as an older sister, the writer who was closest to his mother, next best thing to family. To find that she had overstepped the bounds of objective reporting was a shock that threatened the foundations of the biography.

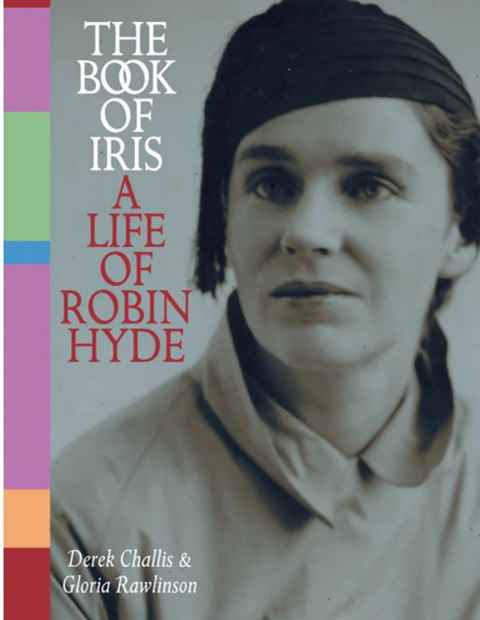

Derek and Lyn reworked the chapters on China, restoring manuscript probity, and the crisis passed. The Book of Iris, published in 2002, was always going to be a work of many voices. Hyde is quoted at length from her letters and autobiographical writings, Gloria is a first commentator in the script, Derek a second, and it is not always possible to tell where one leaves off and the other begins, but the work does seem to stretch and accommodate itself to the varying narrative registers. The Book of Iris is, in the final analysis, a labour of intense love for its subject and needs to be read as part of the family romance Derek Challis inherited and made good.

And the elephant? Her name was Mollie and she was the star turn of the troupe of elephants that toured the country in 1957 with an Australian circus. An untimely snack on fresh tutu foliage in Ohakune left Mollie dead. Derek read an account of the accident in the New Zealand Herald and the University of Auckland Zoology Department got permission from the Minister of Internal Affairs to exhume the elephant.

With local help, Derek removed the head and prepared the skull for a train trip to Auckland. Recounting this singular adventure, he described buying bulk scent from a chemist to disguise the meaty smell of the flensed skull in its rimu sawdust packing.

The skull was still in the Biology Department in 2008 when staff members came across it in a dark cupboard and Derek was called in to tell his part of the story at a symposium for Mollie. Here we learned that Professor McGregor, Derek’s boss, returning from an overseas sabbatical, was not thrilled to find Mollie’s now painstakingly degreased and bleached skull in his museum. Didn’t Derek know that elephants carried anthrax and that the recovery operation in Ohakune might have had serious consequences? More to the point, the technician had unwittingly trumped his professor.

“When McGregor returned to the Department some months later,” Derek recalled, “he was in fact far from pleased to find an elephant’s skull already installed. He had triumphantly brought with him the skull of a largish male elephant given him by one of the institutions he had visited and I think he thought Mollie’s skull somewhat upstaged his own (rather earth-stained) acquisition.”

Derek Arden Challis: October 29, 1930 – January 14, 2021

Edited from an article that first appeared on Newsroom.co.nz and was republished in March 2021 UniNews with permission.