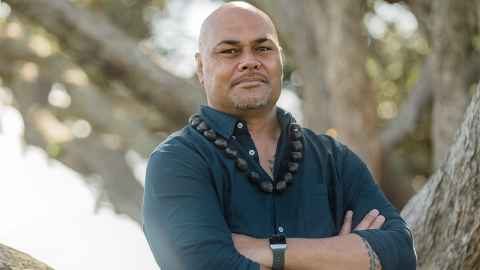

Lama Tone's inspiring story: from rugby to architecture

1 November 2021

Lama Tone was inspired by the buildings he saw all over the world as an international rugby player. Now he's an architecture lecturer who brings a Pacific lens to housing.

Those fork-in-the-road moments of life can slip by unnoticed and only in retrospect do we identify the moment as one in which the course of life was altered.

Lama Tone’s fork-in-the-road moment was unusually dramatic. It was a few minutes into the Pacific Rim rugby finals in Japan, playing for Manu Sāmoa against Fiji in 2001. He was temporarily paralysed after sustaining a neck injury in a tackle.

That was followed by a night keeping very still back at the hotel while his “limbs felt like they were being carved at with a knife”. Back in New Zealand, the MRI scan revealed a ruptured disc. Again. He’d had a similar injury four years earlier, in 1997, a prolapsed disc “from a cowardly tackle from behind” which meant he had to stay away from rugby for a year.

After the 2001 injury, neurosurgeons told Lama that if there was a third time he probably wouldn’t be so lucky. He retired from rugby, including cancelling another year of contract rugby in France. His globe-trotting life as a rugby player staying in five-star hotels, and the future he’d imagined, was suddenly part of his past. He was 30. He’d planned to continue professional rugby for some years yet.

“My life had just done a massive 180 turn.”

Which was, unsurprisingly, followed by some downward spiralling.

“It was my livelihood. I didn’t know what to do, so I had to dig deep.”

To cut the following two decades short: he enrolled as a mature student at the School of Architecture and Planning (SOAP); went on to do his masters in architecture (honours); set up his own practice New Pacific Architecture; and taught part-time at SOAP as a Professional Teaching Fellow. This year, he joined the staff full-time, as a lecturer.

As has been the only way since August, UniNews met Lama on Zoom. He was at home in Māngere Bridge, and appeared in front of the strikingly beautiful background of the interior roof of a fale, designed and built by his friend, architect and alumnus Athol Greentree, for Owairaka-Mt Albert Primary School.

“That’s now a precedent for a project of mine,” says Lama. “For a design and build of a fale at a school in Glen Eden.”

As a kid, I enjoyed using my hands to build stuff. I was always interested in building, but that really exploded when I got to travel in Europe. I was just humbled by the structures, spaces, culture and people.

He agrees there probably aren’t many professional rugby players who have gone on to become architects and designers, but it wasn’t that much of a leap. He had trained and worked as a carpenter while playing club and provincial rugby in New Zealand and was an assistant draftsperson for his uncle’s civil engineering firm in Apia when the family had moved back to Sāmoa when he was 21.

And all that travelling as a rugby player, to Europe, Japan, North America and Canada, had exposed him to some of the greatest architecture of the world.

“As a kid, I always enjoyed using my hands to build stuff. I was always interested in building, but that really exploded when I got to travel in Europe. I was just humbled by the structures, spaces, culture and people.

“I never thought I’d pursue a career in architecture as a youngster. I wanted to be a policeman. It only occurred to me after being injured – and having seen the weird and wonderful forms of architecture throughout my rugby and basketball travels. I was good at maths at school and pretty good at art. I think it was my calling.”

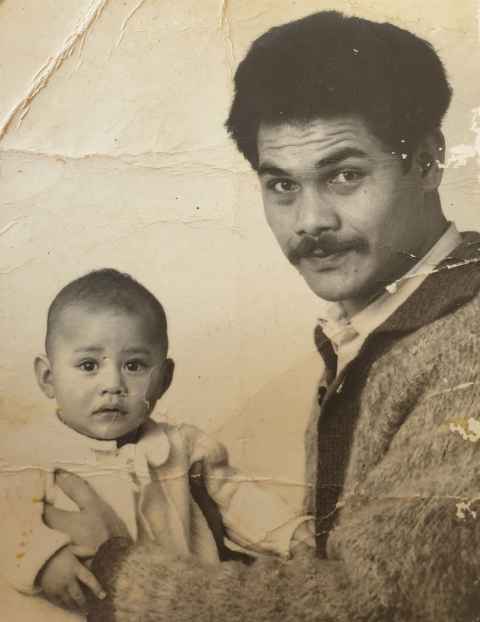

His parents whakapapa to the ancestral homelands of Sāmoa, and he and siblings whakapapa to Māngere and Ōtāhuhu where they grew up and went to school – a younger brother, two younger sisters, and an older half-sister. They all still live in Māngere.

God, family, Sāmoan culture and community are at the forefront of his life, and his family has honoured him with ancestral guardian roles from both parents’ sides. “I have three chiefly titles that whakapapa back to Sāmoa – Pesetā (Dad’s village of Pu’apu’a in Savai’i) and To’oto’ole’aava (Dad’s village of Fasito’o Uta in Upolu), and Fa’amatuāinu (Mum’s village of Lufilufi in Upolu).”

The titles are ali’i (high chief) and tulafale (orator).

He also has an architectural practice in Māngere; the local café was his office foyer.

“I never made any money being a solo practitioner, but it was successful in that I was enriched to hear people’s storytelling, especially Pacific peoples living in the diaspora.”

Pacific people love and come from openness, rather than compartmentalisation. I think generally living with grandparents is one part of the answer to addressing some of the mental health problems our young people are facing in these modern times.

Over the past three years, Lama has also been working with Kāinga Ora on drawing up a brief called the Pasefika Pilot Housing. He’ll be the leading design consultant on the development of a medium-density social housing project, “which will also have universal appeal, but tap into a Pacific perspective here in my hometown of Māngere, South Auckland”.

What tempted him back to a full-time academic role? He’d always enjoyed teaching, and the time seemed right – he recently turned 50 – to do more teaching, but also research. He’s aiming to start his PhD in 2022. Besides, working as an architect in the real world also means working within the constraints of the client’s budget. As a teacher, he can set a hypothetical design brief that allows students to push the boundaries of design – without the constraints of a real-world budget.

“That gives me great creative satisfaction and excitement, guiding them on this part of their journey.”

He packs in a lot. He’s the chair of the Manu Sāmoa Old Boys Association and its former players are involved in community outreach activities, such as visiting retirement villages, hospitals and private residences to sing carols at Christmas.

“We also try to offer insights to assist young people looking at a professional rugby career, and suggest tertiary and professional career pathways. We provide a mental ‘check-in’ for current and former Manu Sāmoa players through just kōrero and talanoa and get-togethers.”

He has plenty of other interests including fishing off his kayak, camping, golf, boxing, reading, archaeology, karaoke, classic cars, movies and theatre. Oh, and coaching the basketball team of his 11-year-old son Levātumau.

“I started helping the coaching staff for his U13 St Peter’s College rugby team. It was Levātumau’s first time playing rugby, but he didn’t like it. He loves basketball though, so I ended up coaching his middle school basketball team.”

Like father, like son. Lama’s first sporting love was also basketball and, at 1.98m, he was cut out for it. He played at high school and for Counties Manukau, and also for Sāmoa in the Oceania Championships which Sāmoa hosted in 1993.

“I got to play with the first-ever Sāmoan/Pacific NBA player.

“But then some village boys came knocking at my door, saying they needed someone to jump in the rugby lineouts and ‘grab them some balls’.”

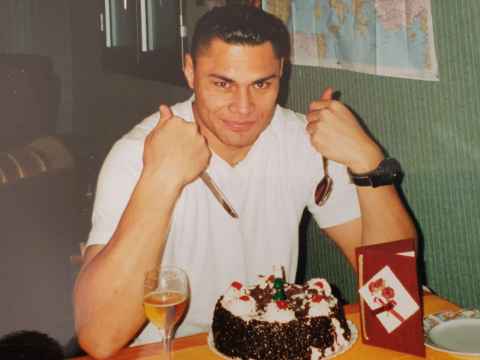

One rugby game led to another and he played for Manu Sāmoa from 1996 to 2001. A highlight was beating the Graham Henry-coached Wales side, in Wales’ new Millennium Stadium during the 1999 Rugby World Cup. “When the whistle went, you could have heard a pin drop.”

And then came architecture, with a focus on Pacific architecture. How would he define Pacific architecture, in a contemporary context?

“I guess it’s about designing for a worldview that’s different from more Western or modern worldviews and discourses.”

That includes designing spaces that break down the walls – literally – and allow for a more open style of living. It is architecture that is sensitive to daily rituals both formal and informal, tapu (sacred) and noa (common), and communal living. It includes designing homes for a more expanded and inter-generational understanding of family.

“Pacific people love and come from openness, rather than compartmentalisation. I think generally living with grandparents is one part of the answer to addressing some of the mental health problems our young people are facing in these modern times.

“We’re at crisis point not only from a housing stock point of view, but also from a design perspective and we need to get these spaces right.”

Story by Margo White

This story first appeared in the November 2021 edition of UniNews.