Marae history project underway at Epsom

26 July 2022

A book celebrating 40 years of the University of Auckland's Epsom marae is underway and looking for any relevant archival material, write two of the project's contributors, Hēmi Dale and Rose Yukich.

The Epsom campus marae is on the move. By 2024, 40 years after opening its doors, Te Aka Matua ki Te Pou Hawaiki will make its way to the University of Auckland’s City Campus, along with the Faculty of Education and Social Work.

Its taonga will be re-homed within a new marae setting. In preparation for the move, a project is underway to compile narratives and archival resources (texts and images) for an illustrated book on the marae’s unlikely backstory.

Led by Te Puna Wānanga (the School of Māori and Indigenous Education), the book will secure the whakapapa of the marae for future tauira, kaiako and manuhiri.

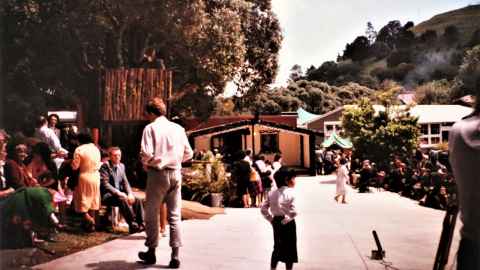

When the marae opened in 1983, on the then grounds of Auckland Teachers’ College, it was only the second marae to be established on a tertiary campus. Over the following four decades, former students and staff have kept its stories alive through regular hui and reunions.

A central character in stories of the marae is Ngāpuhi rangatira, the late Tarutaru Rankin. Steeped in mātauranga Māori, resourceful and inventive, he harnessed the talents of those around him to bring the marae into existence.

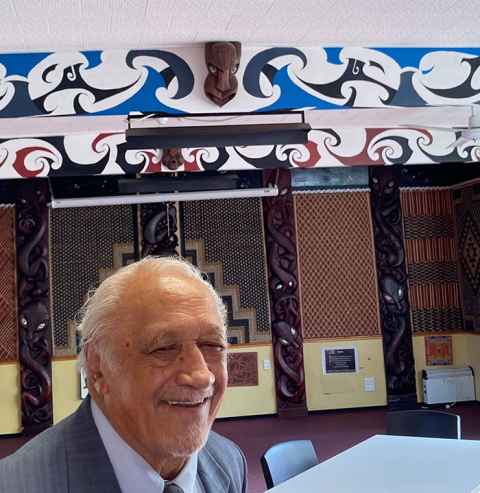

Taru’s colleague and leading Māori educator Tā (Sir) Toby Curtis (Te Arawa) is one of ten people interviewed to date for the book project. He recalls Taru’s courage and agility in the face of official reluctance to publicly endorse the need for a marae.

“Taru was always a couple of steps ahead of everyone, me included!” says Tā Toby.

“One day at the college, an empty prefab on the back of a truck meant for another site on the campus came down the driveway near our office by mistake. Taru said to me, ‘That’s our marae, e hoa’.

"By the time it was about to be lowered into position, he had already organised a kaumatua friend to come and do a blessing or ‘mahi a karakia’. And it’s still there. I call it ‘the stolen whare’ because I knew it was supposed to go somewhere else.”

Transforming the whare whakairo that is Tūtahi Tonu from a dream into a reality relied on talented and committed novices as well as generous donations of labour and goods from the community. Sir Toby marvels at the quality of work that poured from students and other contributors.

“What I find so captivating about the wharenui is that it was built by everybody. People who hadn’t done carving and other arts before were now doing it. We were starting from scratch. Even I ended up carving a wooden mask at the eleventh hour for one of the kōwhaiwhai beams!"

“Taru had a wonderful way of making people do things the right way and achieving outcomes. This place always reminds me of the latent talent people have and that we must find a way for them to express it.”

A flax-roots Māori-led initiative, the marae went ahead without formal permission to proceed. Diplomatic kōrero along with humour were crucial in building understanding and navigating relations across the institution.

Tā Toby and a small group of supportive Pākehā staff acted as takawaenga (go-betweens) during the two years it took to complete the marae.

“My job was to go to the staffroom every day at morning and afternoon tea,” says Tā Toby. “If there were negative comments about the fact that there might be a marae happening, my role was to develop a discussion. We had to convince staff in the most unorthodox way possible.”

He says that while the work was in progress many outside people, including Whina Cooper and Joan Metge, visited regularly to give moral support to Taru and what he was trying to do.

“They knew it was difficult. But, by the time of the opening the rest of the college was very much on board; it had become ‘our marae’ and everyone wanted to come! I couldn’t believe it.”

A flax-roots Māori-led initiative, the marae went ahead without formal permission to proceed. Diplomatic kōrero along with humour were crucial in building understanding and navigating relations across the institution.

The marae history project has generated enthusiasm and goodwill among the wider marae whānau, who realise the time is right for its stories to be recorded in a more permanent form.

The planned book will provide important research materials and teaching resources for students and lecturers and honour the history of the Māori contribution to the Epsom Campus as an integral part of the University’s identity.

The task of drawing together faculty resources to produce the book is ongoing, a tangible expression of Tiriti relations in practice. Book chapters will include Māori understandings of the whenua on which the marae currently stands, high quality images of its taonga and a selection of narratives shared by staff and students.

It will also record the cultural protocols and practical aspects entailed in moving the marae to the City Campus.

If anyone has archival material (images or documents) that may contribute to the marae history project, please contact Hēmi Dale at hemi.dale@auckland.ac.nz or Rose Yukich at r.yukich@auckland.ac.nz

Media contact

Julianne Evans | Media adviser

M: 027 562 5868

E: julianne.evans@auckland.ac.nz