Stem cells could be key to slowing the ageing process

08 September 2022

A “serendipitous finding” by a team of researchers at the University of Auckland could shed light on why women tend to live longer and healthier lives than men.

Dr Trevor Sherwin, Professor of Ophthalmology in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, says the secret to longevity may come down to our stem cells, which play a vital role in creating new cells that replenish our organs throughout our life and keep us healthy for longer.

While studying cell tissue in the eye, Professor Sherwin and his team observed a marked difference in the potency – that is, the ability to replenish cells – of the stem cells of women donors compared to those of men. Even the stem cells taken from women donors in their 70s and 80s were more potent than those in much younger men.

Professor Sherwin says the unexpected finding, which subsequently led him to delve deeper into the link between sex and ageing, could help explain the fact that 95 percent of supercentenarians (people aged 110 and over) are female and unusually healthy.

“It was a completely serendipitous finding that we hadn’t expected. We expected it to be linked to age but we didn’t expect it to be linked to sex,” says Professor Sherwin.

“That led us to look at whether ageing in general is a factor of the stem cells within our bodies.”

Professor Sherwin and his team are now around three years into a research project exploring how the potency of stem cells in men and women differ, and the effect this has on the ageing process.

“What tends to happen is that as you’re reaching the limit of human age your stem cells fail and therefore your ability to replenish your organs fails, and your body just sort of loses its ability to live for much longer,” he says.

Professor Sherwin stresses that the goal is not to increase people’s lifespan, but rather their ability to stay healthy for longer.

“We’re not trying to make people live longer, we’re just trying to make their health span equal their lifespan, so that hopefully for as long as you live you remain healthier.”

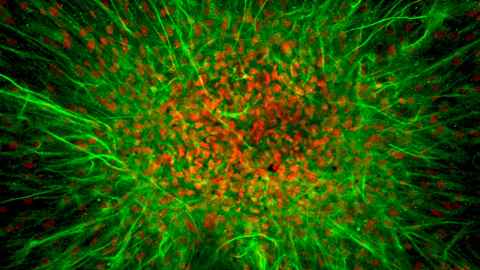

Professor Sherwin says the eye is an ideal model in which to study stem cell health because it has a particularly high turnover of cell tissues, meaning any decline in potency is multiplied and therefore easier to see. Effectively, he says, the health of the stem cells in your eyes could act as an early warning indicator of the health of the stem cells in other parts of your body.

“If your stem cells are a little bit damaged then they’re not able to replicate as much and so therefore we see the effects in the eye earlier than we might see it in other organs around the body.”

As part of the project, Professor Sherwin has been working with Dr Julie Lim, a senior lecturer in the Molecular Vision Laboratory located in the Department of Physiology, to delve deeper into exactly why male stem cells are more vulnerable to the effects of ageing than women’s.

“There is a hormonal link,” Professor Sherwin says. “Oestrogen tends to promote the production of antioxidants in the body, while testosterone tends to do the opposite – it tends to demote antioxidants.”

Because oxidation damages stem cells, the challenge now is to figure out exactly what gene is responsible for causing this damage.

“If we can identify the antioxidant gene that is affected, then we’ve got a potential therapeutic target for trying to stop that cellular damage in our male cells, and hopefully men can live as healthily for as long as women do.”

Professor Sherwin’s research recently received philanthropic funding from the Freemasons Foundation, a boost he says is crucial to the project’s success. Additional funding for Dr Lim’s research has also come from the Auckland Medical Research Foundation and the Save Sight Society of New Zealand.

“All research is very expensive. And because we’re at the stage where we are still in the laboratory aspect of looking at the ageing processes then we wouldn’t be able to run the expensive cell culture techniques, the gene expression techniques without significant funding,” he says.

“So without these generous donors, we might still be just talking about a theory rather than progressing the research that allows us to say it’s a real effect and one we need to be taking account of.”

And because ageing affects everyone, Professor Sherwin says the research has the potential to be hugely beneficial for all of us.

“Rather than [looking at] a specific disease, it’s looking at a process that happens in all of us but that just so happens to work faster in some than in others. And if we can slow that down then we’re going to see an effect in a large number of people quite quickly.”

Media contact

Helen Borne | Communications Manager

Alumni Relations and Development

Email: h.borne@auckland.ac.nz