English language traced back 8,000 years to modern-day Turkey, Iran

28 July 2023

University of Auckland scientists helped reconstruct the emergence of the Indo-European family of languages.

Origins of the English language can be traced back about 8,000 years to prehistoric farmers living south of the Caucasus in what is now eastern Turkey and north-western Iran.

That’s according to research led out of Germany and drawing on University of Auckland expertise. The finding comes after 200 years of debate about when and where the Indo-European family of languages began.

Northern parts of the so-called Fertile Crescent, a region hospitable for farming that curves from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf, may have been where Proto-Indo-European was first spoken.

Indo-European languages are the world’s most-spoken family of languages, numbering more than 400 and including English, Russian, French, Gaelic, Hindi-Urdu, Bengali and Punjabi.

One of the study’s lead authors, Professor Russell Gray, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, is also a professor at the School of Psychology at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland. He described the findings as “robust.”

An international team of over 80 language specialists analysed the spread of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages, including 52 ancient or historical languages, such as Latin and Vedic. Contributing from the University of Auckland were Dr Simon Greenhill in the School of Biological Sciences, Dr Remco Bouckaert in the Department of Computer Science and Professor Quentin Atkinson in the School of Psychology.

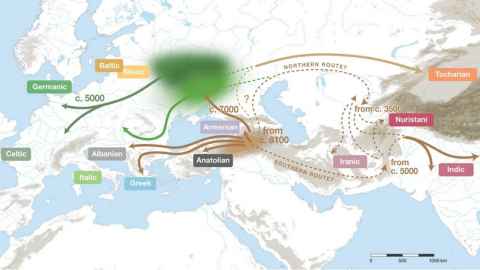

Proto-Indo-European is about 8,100 years old, with seven main branches already split off by about 7,000 years ago, according to the scientists, who claim better data and methodologies than previous studies.

The research, published in the journal Science, may lead to reassessments of the two theories which previously dominated the debate.

The “Steppe” hypothesis suggested an origin about 6,000 years ago in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, an area running through today’s Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan.

The “Anatolian” or “farming” hypothesis suggested an origin 8,000-9,000 years ago tied to the dawn of agriculture in Anatolia, part of today’s Turkey.

The new research suggests Indo-European languages began around Anatolia and moved northwards onto the Steppe, which served as the homeland to the languages which eventually entered Europe.

“Ancient DNA and language phylogenetics thus combine to suggest that the resolution to the 200-year-old Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses,” says Gray.

For the University of Auckland, the research was the third instalment in 20 years of work, which began with a 2003 paper by Gray and Atkinson in the scientific journal Nature.

“This really vindicates our earlier work,” says Atkinson. “The genes and the languages are telling us we were right to challenge the status quo Steppe origin theory.

Languages that derive from the same former ancestor language retain signals of that past origin, and of their divergence since then. By meticulously comparing the languages within a family it is possible to reconstruct aspects of their common ancestor language.

Media contact

Paul Panckhurst | media adviser

M: 022 032 8475

E: paul.panckhurst@auckland.ac.nz