A pacemaker that could help the heart heal

01 December 2025

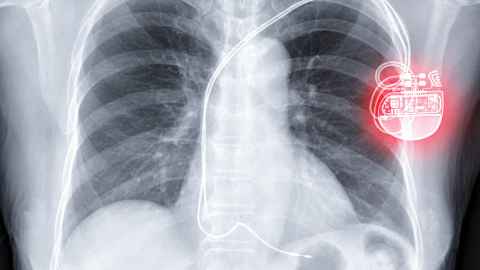

Pacemakers have one basic job: keep the heart beating steadily. But researchers are testing a new device that syncs the heartbeat in a way that may help damaged hearts repair.

In 1958, a brilliant former World War II radar technician called Sid Yarrow built New Zealand’s first pacemaker. It was a large-ish rectangular box and could be attached by wires to heart patients – check out the photo below. The goal of Yarrow’s device remains much the same 67 years on: keep someone’s sluggish or irregular heart ticking at a steady, reliable rhythm.

Now, a new pacemaker being developed at the University of Auckland might go further.

This experimental pacemaker, set to go into a second set of human trials next year, is based on restoring something far older than the technology itself: the natural rise and fall of the heartbeat in time with breathing.

In healthy bodies, the heart speeds up slightly when we inhale and slows as we exhale. The rhythm is subtle, often strongest at night, in children and in highly trained athletes. But it almost always disappears in people with heart failure.

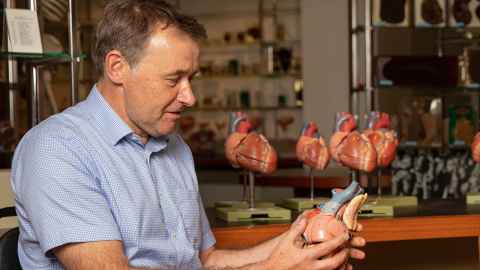

Julian Paton, Professor of Physiology at Waipapa Taumata Rau, the University of Auckland, and director of Manaaki Manawa, the Centre for Heart Research, has spent more than two decades trying to understand why humans have this breathing-linked heart rate variability – and whether it could be important.

“If you look at the evolution of heart rate control, you find even in the very early cartilaginous fish from over 431 million years ago, the way fish breathe, by pumping water across their gills, is in time with a heart rate fluctuation.”

That link continued from fish, to reptiles, to mammals.

“So you cannot help wonder whether it might be doing something good.”

Paton wanted to understand whether this ancient pattern mattered for heart function. The question followed him for years.

In 2011, Paton came to New Zealand on sabbatical and met mathematical modeller Alona Ben-Tal, an honorary associate professor in mathematics working in the physiology department at the University of Auckland. Ben-Tal was also exploring why respiratory heart rate variability existed. She tested a widely accepted hypothesis, but her model suggested it was wrong.

She built a different model, and that pointed to a different explanation: the heart speeding up and slowing down with breathing helped it save energy, giving the cardiac muscle a small efficiency advantage every cycle.

“And this gave Julian this idea that if changing heart rate with breathing helps the heart save energy, maybe if we reinstate respiratory heart rate variability in heart patients who have lost it, it could help the heart heal itself, Ben-Tal says”

This article is a quick taster from the latest Ingenious podcast: 'A pacemaker that could help the heart heal'.

For the full story, listen to the episode.

Back in England, Paton found a physicist, Alain Nogaret, who could build a circuit that linked breathing and heart rate together. In 2016, Paton and Nogaret founded Ceryx Medical and developed the circuit so it could be tested in rats with heart failure to see whether pacing their heart in line with their breathing made a difference.

And it did.

"What we saw was extremely encouraging. We were able to not only push heart rate up during inhalation and bring heart rate down during exhalation, but we also saw a 25 percent increase in the amount of blood being pumped in animals that had received this heart rate variable pacing for two weeks.

“To put that into context, 25 percent is at least three times more than any current therapy given to a heart failure patient in terms of improving the amount of blood being pumped by their hearts. That includes a pacemaker and a lot of drugs.”

Tests in sheep confirmed the 25 percent improvement in blood flow, and revealed something Paton says was “unexpected and incredibly exciting”. The variable pacemaker appeared to help hearts start healing.

“This pacemaker seems to reverse some of the damage that has been done at the level of the mitochondria and at the contractile machinery within these heart cells. If you like, we are repairing heart failure. There is not much on the market that can reverse remodel the heart in heart failure.”

Heart failure is usually caused by damage or weakness in the heart muscle, making it unable to pump blood effectively. Around 180,000 New Zealanders live with heart failure where there is no treatment that can fix the damage. It’s a major cause of death.

Hope for non responders

Martin Stiles is a cardiologist at Waikato Hospital and Professor of Medicine at the University of Auckland. He is leading the world’s first human trial of the Ceryx Medical respiratory variable pacemaker.

He says existing pacemakers work well for people whose heart rate is too slow or irregular. But for those with heart failure, the picture is murkier.

“About one third of [heart failure] patients are what we call ‘non responders’,” Stiles says. They receive an implant but see little improvement.

If the breathing-synced pacemaker can help even part of that group, it would expand treatment options for one of the world’s most common and debilitating conditions, Stiles says. Hence the excitement at the changes seen in sheep hearts.

“I remember seeing those slides from the electron microscopy about the T tubules in the skeleton of the cell repairing themselves in sheep with respiratory variability pacemakers,” he says. “We certainly hoped it would show a difference, but the degree is quite dramatic. It was a real ‘aha’ moment.”

Developing the device from an external box to a fully implantable unit is the next major step. That requires engineering, manufacturing, regulatory approvals, animal testing, more human trials – and significant amounts of money.

“This is a millions of dollars project,” Stiles says.

Many heart failure patients are so breathless they cannot even walk across the lounge into the kitchen to put the kettle on... We want to be able to reverse the damage before it is too late.

Ceryx Medical has just finished a $10 million capital raise to miniaturise the electronics, and the company will need another $10 million next year to take the internal device into the next human clinical trial.

Still, pacemakers are a $5 billion industry, Paton says. There is interest.

The endgame?

“I hope to see what all heart failure patients I have spoken to want, which is to be able to get out of their seats and to be able to walk up their staircase to get into their bed at night. Many of them are so breathless they cannot even walk across the lounge into the kitchen to put the kettle on.

“When heart failure gets really bad, this is what is happening. We want to catch it, and we want to be able to reverse the damage before it is too late.”

This article is a quick taster from the latest Ingenious podcast episode: 'A pacemaker that could help the heart heal'.

For the full story, listen to the podcast.

Ingenious is a podcast highlighting groundbreaking research and researchers from Waipapa Taumata Rau, the University of Auckland. Find all our episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Pocketcasts.

Media contact

Nikki Mandow | Research communications

M: 021 174 3142

E: nikki.mandow@auckland.ac.nz