Innovation and entrepreneurship: The shape of things to come

3 June 2019

To move beyond an economy founded on agriculture and tourism, New Zealand needs the type of entrepreneurial activity being undertaken by world-class researchers at the University of Auckland. By Gilbert Wong

Think of New Zealand as a business asking for advice from the accountant. She sits down to review Aotearoa Inc's revenue streams and is unimpressed. The majority of Aotearoa Inc's revenue comes from just two sources, primary industries, mainly dairy and meat exports, and tourism. New Zealand no longer lives off the sheep's back, but the sectors the country has gravitated towards do little to spread economic risk and they don't look like the future in an age of environmental stress.

Professor Olaf Diegel who leads a new University of Auckland initiative, the Creative Design and Additive Manufacturing Laboratory, puts it this way: "There's only so much milk you can produce. Fonterra is doing good and new things with milk. But I think we're not far off reaching a plateau in what we can do here. There are only so many trees we can grow, only so many cows we can milk."

Our two main earners rely on the twin naturals, resources and beauty. As the OECD put it in a 2017 'Review of New Zealand Environmental Performance', our growth model "based largely on exploiting natural resources is starting to show its environmental limits". Peak milk and peak tourism are coming, the only question is when.

The puzzle has more pieces. Every society now faces the unpredictable buffeting of the tornado pace of technological change. As the World Economic Forum noted, "By one popular estimate, 65 percent of children entering primary schools today will ultimately work in new job types and functions that currently don't exist."

If the future is not what it used to be, Wendy Kerr, the director of the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (CIE), has a ready response.

"We need to diversify where we get our earnings from and the University is key to that. If we want to create a value-added knowledgebased sector and create more jobs that aren't based on primary industries and tourism, then innovation and entrepreneurship is where those jobs will come from."

If we don't take the opportunities from someone's research, then someone elsewhere will.

If the CIE is how the University plants the seeds of innovation and entrepreneurship, Will Charles, the executive director for commercialisation at UniServices, stands at the sharp end of the journey: where research becomes intellectual property in search of market opportunity.

For Will, it is simple. New Zealand plays in a global game it cannot afford to lose. "Knowledge has no boundaries. If we don't take the opportunities from someone's research, then someone elsewhere will."

Innovation and entrepreneurship are founded on research excellence. Research excellence attracts the brightest students and best postdoctorates. The best post-docs become the brightest professors of the future. Without them, the University slips in world rankings and risks being dragged into a downward spiral, bad news for any university, but a disaster for the prosperity of New Zealand.

Will says: "A smart nation used to be measured by research papers and graduates. Today, a smart nation is determined by how well it converts research into economic or social activity."

Wendy and Will are key players in a national imperative for which the University of Auckland has been a strong advocate. The goal is to transform New Zealand from a country reliant on the export of natural resources, with little added value, to a smart nation in the global knowledge economy.

Wendy and the team at the CIE are the hub for the University's efforts to nurture and coach the next generation of innovators and entrepreneurs. The Centre's programmes range from a Master of Commercialisation and Entrepreneurship through the School of Business, to a range of experiential programmes designed to ignite new ideas and coach new ways of working.

To me, it's not fail fast, fail often, but fail extra fast, fail extra often.

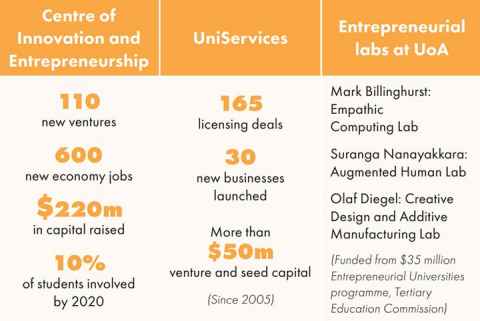

Most notably, the Velocity programme, launched in 2003, has now helped more than 110 new ventures get started, which in turn have raised more than $220 million in capital and created more than 600 new economy jobs. A mix of design-thinking boot camps and innovation workshops, the programme backs aspirations with cash in an annual $100k Challenge to choose the teams with the best ideas about new ventures, social enterprises and university research.

The big picture is for 10 percent of the University's 40,000-plus students to be engaged in the centre's programmes by 2020. In 2018, 2,557 students took part, with 131 graduates in the Masters of Commercialisation and Entrepreneurship since 2012.

Wendy, looking at the year-on-year trend, reports a 320 percent lift since 2015 and is confident of reaching the 2020 target. Will has been the commercialisation lead at UniServices since 2005. In the five years to 2018, UniServices has assessed 710 inventions for commercialisation and licensed more than 270 patents. Spin-out companies have raised more than $148 million over the same period.

His latest project, Return on Science, is part connector, part X-Factor for commercialising research and new ideas. Return on Science enables researchers, start-ups, investors and entrepreneurs to tap expertise and networks through nationally convened investment committees with experts in the science and business side of agritech, biotech, life sciences, information and communications technology and physical sciences. A parallel programme, Momentum, does the same for students.

Distinguished Professor Dame Margaret Brimble is in the School of Chemical Sciences and the first New Zealand woman scientist to be elected a Fellow of London's Royal Society.

A world-leading researcher, she has seen her work become the foundation for companies in the globally competitive business of drug development.

Neuren Pharmaceuticals, listed on the ASX in 2005, has progressed to Phase 3 clinical trials, the final step before FDA approval, for a new drug, trofinetide, that Dame Margaret discovered to treat Rett syndrome. A neurodevelopmental disorder, it has been described as a combination of autism, cerebral palsy, Parkinson's, epilepsy and anxiety disorders. It only affects females, with a prevalence of one in 12,000, enough for the devastating congenital condition to be the second most common cause of severe intellectual disability after Down syndrome. Trofinetide has also been trialled for patients with Fragile X syndrome and traumatic brain injury.

Dame Margaret says: "There's nothing better than being in front of a class of organic chemistry students and telling them that one day they could make a drug for Rett syndrome." A further strand of her research is behind a new generation of cancer vaccines, based on her novel peptide platform technology, being developed by an American company, SapVax.

Local company Living Cell Technologies has also licensed Dame Margaret's compounds to develop treatments for migraine and obesity. For Associate Professor Suranga Nanayakkara, the big questions are about how to humanise technology. In 2014, Time magazine's innovation issue singled out his FingerReader, which allows a visually impaired person to scan text at the tip of their finger and read it aloud, as opening a new world of independence for the blind.

Suranga and his team relocated from Singapore to set up the Augmented Human Lab in the Auckland Bioengineering Institute in 2017 under the Entrepreneurial Universities programme funded by the Tertiary Education Commission. The $35 million programme was the idea of the University of Auckland and enables world-leading entrepreneur researchers to relocate to New Zealand.

"There is no way to survive if we don't innovate," says Suranga. "The simple reason is that technology is changing everything. Science fiction is becoming reality today." Distilled to its essence, innovation is problem solving.

Technology is changing everything. Science fiction is becoming reality.

"Nobody can predict the future, but we know there will be challenges, and if the skill we coach is actually problem solving and how to identify opportunities that respond to problems, that's the mindset and culture we need."

Under Suranga's mentorship, students have set up two start-ups, one looking at further development of the FingerReader concept, the other based on a shoe that gives feedback on gait and other data for anyone from a high-performance athlete to a person with a mobility issue.

He sees New Zealand as having the DNA to make the shift to an innovation culture. Here, he says, it is okay to question the accepted wisdom. "Elsewhere, education tends to be driven by the idea that there is only one answer and whoever gets there fastest wins. The problem is, that leaves no room for innovation."

Olaf Diegel also joined the University under the Entrepreneurial Universities programme. He came from Sweden and is an innovator in Additive Manufacturing (AM) or 3D printing, a disruptive technology already affecting manufacturing and global supply chains and creating new markets for the mass customisation of products.

To demonstrate the technology in a mainstream kind of way, he has made more than 70 3D printed guitars that he's had shipped to Auckland and which are on display in his office. But that's just the hobby side of his work. In his lifetime, he predicts the bio printing of human organs from kidneys to livers, using stem cells. "Once we crack the vascular system we will progress to complex organs."

Olaf has begun discussions with local companies about projects from better prosthetic limbs to nutrient-laden printed food in agar gel. For New Zealand to shift to an innovation mindset, Olaf says we need to reframe how we see failure. Innovation recognises that eight out of ten ideas turn out to be rubbish. "To me, it's not fail fast, fail often, but fail extra fast, fail extra often."

For New Zealand to prosper, we need to get past the perception that an entrepreneurial academic is a contradiction in terms. Will defines an entrepreneur as a person who has a vision or a burning question and is adept at putting together the people and money to achieve that vision. "The University is full of highly active researchers," he says.

"They live it, they breathe it, they fizz with it. They might not express what they do in the way society traditionally thinks of as an entrepreneur, but this is very definitely entrepreneurial activity."