Extinction of a native freshwater fish – will history repeat?

23 July 2019

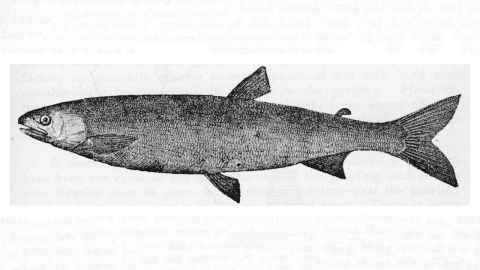

It is the only known New Zealand freshwater fish to have gone extinct but the speed at which upokororo disappeared forever has remained something of a puzzle.

Now a new study has shown the missing piece of the puzzle may have been poor water quality and degraded habitat due to human activity around the time of European settlement.

The extinction of upokororo (or NZ grayling, P. oxyrhynchus) was remarkably rapid ecologically speaking. Still common in 1860, by the early 1900s the fish were being reported as scarce with the last-ever catch recorded in 1923.

Despite unverified sightings in later decades, there is no official record of the fish being seen again after that date.

“In ecological terms this was fast,” says University of Auckland PhD candidate Finn Lee who, along with Professor George Perry from the School of Environment, has carried out the first-ever comprehensive study on why upokororo became extinct when other freshwater species managed to survive.

Up to now it was widely assumed habitat degradation, over-fishing and the introduction of trout, a key predator of larvae and juvenile upokororo, were the three drivers. Because upokororo are a shoaling species, and numbered into the tens of thousands if not millions, they were easy prey for fishers who killed them in the thousands, often chasing them into a confined space and scooping them up in nets. So abundant were they, they were used as fertiliser on market gardens.

But habitat degradation, fishing and predation by trout don’t fully explain the speed of upokororo’s disappearance, or the fact they disappeared from isolated pristine rivers.

After examining hundreds of historic records and using modern data modelling techniques, Mr Lee and Professor Perry say another factor may have been the nail in the coffin for upokororo.

That was the species dispersal strategy. Upokororo were amphidromous – they migrated from river to sea and back at some point in the life cycle - but unlike salmon, it’s believed they did not instinctively return to the place they were born. This meant they returned to breed in rivers and streams of poor water quality or inhabited by trout and this in turn led to what ecologists call population ‘sinks’.

Sinks is the term is used to explain a ‘sinking lid’ ecological theory whereby once-healthy populations do not reproduce at a rate high enough to establish sub-populations and so populations slowly ‘sinks’.

“Our modelling shows these population ‘sinks’ could be the vital missing link,” Mr Lee says. “We factored in over-fishing and predation by trout and while those things made a big difference, once we factored in dispersal among rivers and lower breeding rates from poorer quality habitat, then it clearly showed how the fish became extinct so fast.”

The researchers say the study has significant implications for other freshwater fish, more than 70% of which are at risk for under threat of extinction. In particular, there are concerns over whitebait, and whether current restrictions are enough to protect them.

Professor George Perry says like other countries, New Zealand faces big challenges to protect its freshwater species but in order for history not to repeat itself, we need to know what happened in the past.

“Globally freshwater ecosystems are under immense strain, facing habitat loss, invasive species, climate change and over-exploitation, so understanding what happened in the past might allow us to stop extinctions of freshwater biota in future.”

The Australian grayling is closely related to upokororo and is listed as a vulnerable species under Australian environmental law.

The study is published in Freshwater Biology

Media contact

Anne Beston | Media adviser

DDI 09 923 3258

Mob 021 970 089

Email a.beston@auckland.ac.nz