Anthony Hoete: architecture out of the box

27 October 2020

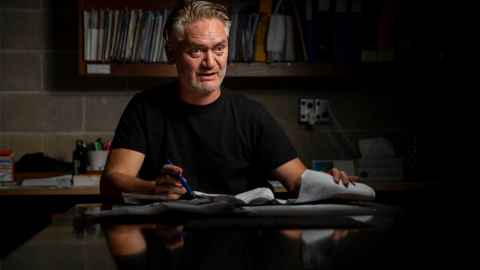

Unconventional award-winning architect Anthony Hoete has brought his skills and vision back to New Zealand and the University of Auckland. He talks to Pete Barnao.

If you were ever trying to get a child interested in architecture, building their school out of Lego is a sure-fire way to pique young interest.

That’s what Kiwi architect Anthony Hoete did for one of his many innovative projects. Pupils and parents at a primary school in London were given 3,000 bricks so they could contribute to the design process for their school. Anthony had wanted them to be part of the process, but knew they would feel overwhelmed at having to draw a design.

“Lego bricks, rather than drawings, designed the school,” says Anthony. “During the process we realised, instead of just designing the school, why not make the school out of Lego bricks?”

Anthony sourced the bricks from Legoland then coated them for fire compliance along with the usual tests for structural integrity. The result was a black and white façade built with 1.4 million Lego bricks, breaking with adult conventions that favour primary colours for children’s equipment. He also incorporated artworks by each of the school’s 400 pupils.

“The architect acted as builder while the children played architect,” Anthony says. “It was an example of role play.”

Professor Anthony Hoete is back home to play a different role now. He has returned to the School of Architecture and Planning, from where he’d graduated in 1990 with honours in architecture, as Professor of Architecture (Māori).

Anthony, a Kawerau College old boy, has spent three decades overseas building a reputation as a world-class teacher, researcher, entrepreneurial architect and developer. He set up WHAT_architecture in the UK in 2002 and a development company, Game of Architecture, in 2015.

Accolades include a UK Prime Minister’s Award for Better Public Building and awards from the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Civic Trust.

He likens architecture to a game, and explores how architectural practice can be played better.

“One way is to question how we interpret, manipulate, challenge and bend the myriad rules that inform architecture to produce better outcomes for the built environment,” he says.

He says the architect’s role can be expanded to include that of the developer and builder. His entrepreneurial side certainly embraced that idea around the time of the 2008 recession.

“WHAT_architecture needed to reconfigure so we set up WHAT_developments as well.”

The company acquired land and developed sites. One acquisition was the old Shoreditch railway station in London, bought at auction.

“We didn’t win it at first, but the winner didn’t produce a banker’s cheque. We’d taken the deposit with us, we had $70k in cash in a briefcase. Cash talks.”

While they were going through planning to develop the site, interest on the mortgage needed to be paid.

“We started hiring out the building for raves ... raves in the railway station… with our Russian DJ Nina Kraviz. The raves could bring in $50,000 on the bar and £10 a ticket. We covered the mortgage that way.”

Another temporary out-of-left-field idea for the site was a hot tub cinema.

“That’s basically six people in an inflatable tub paying £35 a head for champagne and movies. Millennials loved it.”

He says those ideas are examples of an architect breaking out of the box.

“When an architect is a developer, they’re no longer the passive recipient of a brief,” says Anthony. “The architect can drive the project from the outset when they’re involved in site acquisition… you’re involved in the economic feasibility and empowered by setting the brief.”

Anthony has a masters in architecture from University College London (UCL) and a PhD from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. Since 2013, he has been an honorary senior research scholar at UCL, specialising in ‘future heritage’.

I do identify strongly as a New Zealander – not least because I’m Māori. That gives me a strong connection back to the land and iwi.

In the UK, Anthony worked with the UK National Trust and Heritage New Zealand to secure the future of the historic Hinemihi meeting house.

Originally sited in the ‘buried village’ of Te Wairoa, where it sheltered survivors of the 1886 Mount Tarawera eruption, the building was relocated in 1892 by the Earl of Onslow to a park in Clandon, Surrey. Anthony’s group brokered an exchange that will see Hinemihi returned to New Zealand and a new pan-iwi whare constructed in the UK. The agreement is the culmination of years of creative problem solving and delicate negotiations. But Hinemihi has also shaped Anthony’s ideas about buildings.

“The significance of these buildings lies not in their material ‘bricks and mortar’ but in their use, in the past, present and future.”

Anthony says his Māori heritage is a factor in calling him home. He’s of Patuwai hapū, of Ngāti Awa, from Motiti Island near Tauranga. He would like his 16-year-old son Māui Pehiamu O Patuwai Roger – educated in the inner London borough of Hackney – to learn its tikanga. Māui will arrive in New Zealand as soon as possible and also once an airline carrier agrees to bring over the canine member of the family, an Akita dog named Chiba.

Chiba now has his own Instagram account @thebarkitect.

“I arrived home and was asked to be the international judge for the 2020 NZ Architecture Awards, the winners for which were being announced on 5 November. NZIA wanted me to get active on Instagram as we toured the entries around the country.”

He says the chance to see new architecture or restorations reconnected him with New Zealand.

“I’ve been out of New Zealand for more time than I was in it,” he says. “You pass that threshold and sort of question whether you’re a New Zealander still, although I do identify strongly as a New Zealander – not least because I’m Māori. That gives me a strong connection back to the land and iwi.”

He and the other judges travelled for nine days, covering 2,000km and visiting 47 projects.

“It was a great welcome mat and allowed me to see the lay of the land.”

He says another factor drawing him home was the opportunity to undertake research in Māori and Indigenous architectural projects, including Māori social housing and “unlocking” Māori land, even on his tūrangawaewae, Motiti Island.

“It’s been bequeathed through successions of generations, but it’s all locked up. Motiti is a bit lost in time; they haven’t even planted a tree. That’s partly because they haven’t worked out a good economic model and that’s happening with a lot of Māori land.”

He’s keen to supervise theses in what he calls Ngārchitecture, or new Māori architecture. He will work with Professor Deidre Brown, head of the School of Architecture and Planning, and is teaching the design studio ‘Housing Puzzle’ with Matilda Phillips. He is also co-director, with Dr Karamia Muller, of a new hub called the Sites Pacific Research Hub, looking at what’s specific about South Pacific architecture. He has an eye on high-density building solutions that yield more affordable housing.

“One model of interest could be instead of individual houses, we build clustered rooms. I’ve noticed that older people, for example, don’t want to live by themselves. They want their mates around them. How can we achieve that?

“That’s one of the good things about being back in an academic environment – you have time to conduct important research that affects people’s lives.”

This feature first appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of Ingenio magazine.