The democratisation of nautical battles

22 February 2021

Opinion: Diane Brand looks at how an exclusive yacht race between world superpowers became a 20th century media phenomenon, accessible in ways never thought possible.

Rome’s ancient Colosseum and Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour are outdoor arenas that have hosted some of the most extreme maritime challenges in human history. The former is a monumental edifice and the latter is a naturally occurring space, but they both brilliantly accommodate nautical battle grounds for public entertainment.

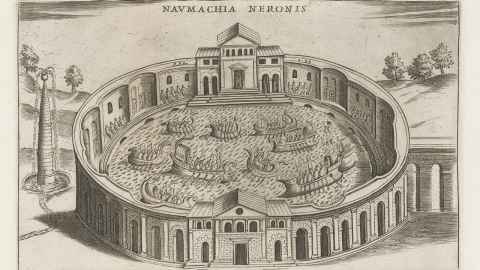

Around 50 BC the river Tiber was excavated to accommodate naumachia or large-scale naval battles which commemorated Roman sea victories. By 85AD these events had migrated to a flooded Colosseum, involved a cast of over 3,000 prisoners, were enjoyed by audiences of 60,000-80,000, and were fought to the death. Two fleets of vessels and two crews were pitted against one another in the tradition of ‘group combat’ rather than gladiatorial combat. These were special and expensive commemorations reserved for exceptional occasions occurring decades apart.

However, the constraints of built amphitheatres forced compromises in vessel scale, mobility, and draught, with the entertainment being more focused on hand-to-hand combat than grand maritime manoeuvres. Naumachiae continued to entertain elites at royal celebrations across Europe until the 19th century. A naumachia called ‘Those about to die salute you’ by artist Duke Riley was staged in 2009 at the Queens Museum of Art in New York.

A naval challenge of a kind is currently taking place in the outdoor arena of Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour. According to Team New Zealand’s CEO Grant Dalton, racing for the 36th America’s Cup has been deliberately sited in the enclosed waters of Motukorea Channel and the Rangitoto Channel (which form the approaches to the Port of Auckland) to maximise the view of the spectacle from land. The participating AC75 yachts are large and sail like rockets, adding a vivid visual spectacle to the ever-present danger of match racing at high speeds.

This has been the way Aucklanders have watched water races since the early colonial days when gaff-rigs (traditional yachts with large top sails) and brigs (square rigged double masted ships) raced wāka, and large amounts of money changed hands in wagers. The Waitematā Harbour provides a series of perfect bowls of space which form outdoor arenas for both local regattas, and the courses set by the America’s Cup Race Committee.

The America’s Cup began as a yacht race where the challenger had to build a yacht, sail it across the Atlantic to the Cup venue and then perform in a series of races to win the silverware. Founded in Britain, the challenge quickly became dominated by the New York Yacht Club. This game was always stacked against the challenger as an ocean-going yacht needed to be more robust and therefore heavier than an in-shore racer.

The US held the cup for 128 years, until in the late 20th century the Cup was won first by Australia in 1983 and much later by New Zealand in 1995, introducing Southern Hemisphere locations into the mix. The Cup was even won by land-locked Switzerland in 2003 and sailed in Valencia in 2007 and 2010 before returning to America once again in 2013.

An exclusive 19th century yacht race between the world’s superpowers became a 20th century media phenomenon increasingly modelled on the Formula One format, and broadcast on television to world-wide audiences. For most of the Cup’s history, the race has been sailed on offshore courses away from the viewing public, either in Cowes or Rhode Island. Public engagement began with making the syndicate bases visible or accessible, first in Fremantle in 1986 and then in San Diego in 1995.

In Auckland’s Viaduct Harbour, the cup facilities were integrated into a new mixed-use urban extension of the city for the 2000 and 2003 challenges, but the racing was well away from public view in the Hauraki Gulf. Valencia followed suit building a sophisticated urban quarter for the America’s Cup Village at the old fishing port, but public accessibility was compromised by overbearing security in the wake of 9/11 and other incidents of international terrorism at the time. The public in these settings got to see the yachts leave and return to base in style, but the racing itself was remote and televised with computer graphic enhancements on outdoor screens.

The natural arena idea was revived in the San Francisco challenge in 2013 with the land captured waterways and filigree of wharf structures of the Bay Area creating the perfect observation platform for the competition, and again on the Great Sound in Bermuda in 2017. This may have inspired the New Zealand organisers to facilitate people lining the coastal promontories or watch from vessels anchored on the race-course boundaries as these nautical flying machines cut up and down the harbour at astronomical speeds.

The spectacle is all the greater for the scale (26.5 metre masts) and airborne demeanour of these flying machines which reach speeds of over 50 knots (the average sailing speed range for a pleasure yacht is 6-12 knots) as they foil around the course. They can be easily seen on a backdrop of wind ruffled water from an elevated vantage point as they tack and gybe up and down a course for 4-8 legs depending on wind speed.

Although modern America’s Cup crews do not face death as an outcome, the stakes are high, with syndicates investing many millions of dollars to complete, and sailors having to be the top athletes of their kind. The vessels have increased in size over time to maximise speed, unlike the Colosseum vessels which were miniaturised and modified to have shallow draught hulls, and the technology is now about the yachts and not the engineering feats of flooding an arena.

An urban harbour arena such as the Waitematā is the perfect venue for an America’s Cup race as it maximises sport, spectacle, super-scaled super-funded vessels, land enclosure, security, public participation and controversy. It is a venue future cup-holder countries would do well to emulate.

Professor Diane Brand is Dean of the Faculty of Creative Arts and Industries.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from The democratisation of nautical battles 22 February 2021.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz