Murray Edmond: Auckland was revolting in the 1960s

29 April 2021

Writer Murray Edmond explores the cultural revolt in Auckland in the 1960s in his new book out in May.

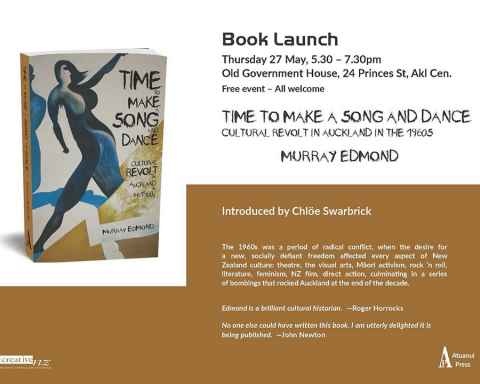

Murray Edmond is best known as a poet, playwright, editor and critic. He was an associate professor of drama at the University of Auckland before he retired. This month he releases a cultural history of Auckland as the city was reinventing itself. His book isTime to Make a Song and Dance: Cultural Revolt in Auckland in the 1960s.

He answers a few questions about its subject material.

Did Auckland even have a culture to revolt against?

That has always been Auckland’s problem – both real and perceived. Dunedin had Robert Burns and Christchurch had Landfall and a cathedral and Wellington had the Literary Fund, a Symphony Orchestra, the National This-and-That and then an Arts Council, but what did Auckland have? Auckland just kind of grew. Rip-offs, war, stolen land, trade, commerce, sport, beaches, yachts and immediately another joke – ‘City of Sales/Sails.’ That was its culture, real and perceived. But in the 1960s, this changed.

You mean sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll?

No. That was the 1970s and later. Deeper changes than those. In the 15 years after the Second World War, Aotearoa grew richer and the population increased. But these changes were greatest in Auckland. A large part of the ‘Second Great Migration’ – the movement of Māori to the cities – came to Auckland. It was a ‘co-opting of an urban working class,’ as Donna Awatere-Huata describes it.

By the beginning of the 1960s, those born during and after the War were turning into adults. Their connection with the War and the world before it was weak. They were looking for a new world to invent and their outlook became more international. They looked around and saw they were living in an almost-city, no longer just a glorified small town.

At the same time, we had stirrings of Pākehā waking up to a bicultural world. Some people set out to change things. The book tells a number of different tales of success and disaster, and of resistance from the Auckland bourgeoisie. The Auckland City Art Gallery we now have begins with director Peter Tomory’s conflict with the Auckland City Council.

The book opens with the moving stories of Arapeta Awatere and Bob Lowry, both of whose lives ended tragically. Were you aware of the details before you began writing?

Yes, I was. In some ways, those sad stories are well-known. Those men both belonged to the world before the War and of the War. That first chapter looks at the accounts written by their daughters, Donna Awatere-Huata and Vanya Lowry, about their fathers. I wanted to write about the writings of these daughters, who were children of the 1960s. The daughters’ writings are as moving as the tales themselves.

Also buried and forgotten has been Allen Curnow’s two decades of playwriting and involvement with theatre, from the late 1940s to the late 1960s. Now you’d think he’d only ever been a poet.

Theatre producer Ronald Barker comes across as a fascinating figure and his dismissal from the Community Arts Service distasteful. Allen Curnow emerges from that story impressively, as Barker’s defender. Was that intended?

Yes, Barker’s story has been buried and forgotten. His loss had a profound impact that resulted in the very conservative development of theatre in Auckland for a long time. Also buried and forgotten has been Allen Curnow’s two decades of playwriting and involvement with theatre, from the late 1940s to the late 1960s. Now you’d think he’d only ever been a poet. So there was certainly an intention to ‘restore’ in that chapter.

Was there a sense of collectivity and movement for change among young people in the 1960s you haven’t seen since? Was counter-culture a more popular stance?

It’s hard to measure one era against another. The collective opposition to the Pākehā All Blacks tour to South Africa in 1960 – No Māoris No Tour – was vocal, but still very small. A larger collective movement for change in Aotearoa only begins to form at the end of the 1960s.

By 1970 the anti-Tour movement can march 10,000 down Queen Street on Friday night. The Young Māori Conference in 1970 defines the direction of future protest ‘Hold fast to your language’ and ‘Not one acre more’.

In 1968, 75 brave citizens sign a petition for Homosexual Law Reform which is ignored. But what surprised everyone, and hasn’t been seen before or since and has also been rather forgotten, was the series of 13 political protest bombings that took place in Auckland from April 1969 to July 1970.

And you cover this in the book?

Yes, the final chapter looks at the bombings. Other chapters look, variously, at moments of decisive revolt for women, for the fine arts, for music, for festivals, and for film and television, and how Auckland of the 1960s was being depicted in novels written at the time.

There was a lot happening, wasn’t there?

There was indeed. In the 1960s, led by a process of cultural revolt, Auckland was inventing a new self.

Time to Make a Song and Dance: Cultural Revolt in Auckland in the 1960s (Atuanui Press, $38).

This interview first appeared in UniNews May 2021.