Breaking it down with sustainable resource recovery

1 July 2021

Sustainable resource recovery students figure out how to dispose of waste safely and in a way that's good for the planet.

Whey waste is a pain to get rid of. Dairy manufacturers use acid whey to create cream cheese and Greek yoghurt, and sweet whey to create protein powder. But the leftover whey waste neutralises the bacteria that breaks down dairy, which must be broken down by special bacteria in a wet-waste treatment facility to separate the whey into different tanks.

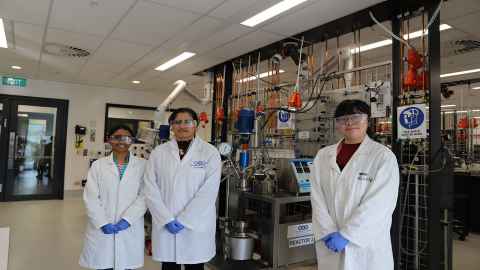

That’s where Masters student Susanne Mathews and the Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering comes in. Mathews is trying to figure out how to hydrothermally treat whey waste so it doesn’t kill the bacteria that breaks down dairy. If successful, the technology can be implemented to discharge whey waste into normal wet-waste treatment facilities without corrupting the disposal process.

Mathews’ thesis is one of several sponsored by EnviroWaste, which is primarily focused on waste management but is transitioning to a resource recovery pathway. Larisa Thathiah, Sustainability Manager at EnviroNZ, says the company cultivated its relationship with The University Faculty of Engineering about four years ago, to recruit students into industry. Now, Larisa says, EnviroNZ would like to see the relationship become two-way, in which the company sends employees to the University to upskill.

Associate Professor Saeid Baroutian agrees. His current research programme is industry-oriented, providing with hands-on, practical topics, supervision and site visits with EnviroNZ employees. Now Baroutian is enrolling students and industry professionals in a new Sustainable Resource Recovery programme that will not only teach the latest technologies, but also evaluate each technology’s fit-for-purpose against societal, economic and legal aspects of resource recovery.

From a job opportunity point of view, Baroutian sees industry keen for more candidates with these skills.

“The cost of raw materials are increasing and everyone needs to show they are meeting sustainability targets,” he says. “There is a need for new graduates and new ideas to address industry’s evolving sustainability goals.”

In addition to Mathews, EnviroNZ is sponsoring two other Masters projects.

Nerischka Thathiah’s thesis hopes to use anaerobic digestion to extend the range of compostable objects to paper and cups. Her research tests wet anaerobic digestion on a slurry of food waste provided by EnviroNZ. The digestion happens in one bottle and displaces gas into another. The gas is then measured to calculate the optimum pH for anaerobic digestion. If the process is viable, EnviroNZ can capture CO2 and methane gas from decomposing landfills and use it for fertiliser or electricity generation.

Ellen Liew Wymei is investigating leachate, an often toxic fluid that percolates through landfills. Her thesis involves discovering how leachate fouls membranes and recommending feasible options to fix that to EnviroNZ.

In order to break our linear habit with waste, from extraction and production to consumption and waste generation, Baroutian says we need to come full circle.

“We need to take those materials we consider waste and look at them as resources,” He explains. “It’s not easy. We need innovative technologies to enable that circle.”