Hunt for blood marker for endometrial cancer

21 October 2021

Endometrial cancer is striking younger women. Detection and treatment could be improved with a first-of-its-kind blood test.

Endometrial cancer, also known as uterine cancer or womb cancer, has long been thought of as a disease of older women, relatively easy to detect because it causes post-menopausal bleeding.

However, endometrial cancer is increasingly occurring in women who still get their periods, making the cancer more difficult to detect. That’s why University of Auckland researchers are working on developing a first-of-its-kind blood test to screen for endometrial cancer.

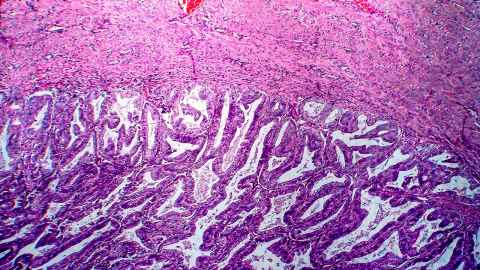

Endometrial cancer occurs in the endometrium or inner lining of the uterus. It’s the fifth most diagnosed cancer in New Zealand, with some 600 new diagnoses a year. The incidence is rising, which may be related to rising obesity rates, because obesity is a risk factor. When endometrial cancer is caught in its early stages, as tends to be the case in older women, it usually has a good prognosis, in part because treatment typically involves hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus.

However, when endometrial cancer has progressed to a later stage before being caught, the prognosis is not as good. Younger women are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage because bleeding from the tumour is easily confused with menstrual bleeding. Even bleeding between periods or heavier-than-normal bleeding – symptoms of endometrial cancer – can have many causes other than cancer. What’s more, treating endometrial cancer in younger women poses a challenge because of the need to preserve fertility, making hysterectomy unsuitable.

Cherie Blenkiron, a senior lecturer in cancer biology in the Department of Molecular Medicine and Pathology is leading the one-year project to develop a blood test for endometrial cancer.

Blenkiron began her research career more than 20 years ago in the UK, focusing on ovarian cancer. Since then, she has worked on breast and other cancers but is glad her current project, has given her the change to return to gynaecological cancers.

“My whole team is female and I think we’re all somewhat driven by the idea of seeking good health outcomes for women,” says Blenkiron. “In my experience, women bring a different perspective to research. We’re open to going out and talking to people in the community rather than thinking, ‘I’m a biologist; I need to be in the lab.’”

Historically, New Zealand has a poor record in women’s health, particularly gynaecological cancers. From the 1960s to the 1980s, women who were patients at National Women’s Hospital in Auckland were unknowingly subjected to an unethical experiment in which women with abnormal cervical cells weren’t treated or even informed about their condition but merely followed to see if they developed cervical cancer. Some died as a result.

Funding for gynaecological cancer research is still not what it should be, says Blenkiron. However, she is grateful to have received funding from the University of Auckland’s Centre for Cancer Research and the Li Family Seeding Grant has helped her set up her own research group and drive her own research agenda.

We’re going to use those tumours to look for molecules within the tumours that we can then hunt for in the blood.

Unlike cervical cancer, which can be detected at an early stage through cervical smears, also known as Pap tests, there is currently no screening test for endometrial cancer. Blenkiron and her team aim to change that.

“The traditional approach to finding new blood markers would be look for molecules that are present in the blood of endometrial cancer patients and compare that with the blood of healthy women to identify things that are elevated in the patients,” says Blenkiron. “There are so many factors, though, that can affect what’s in your blood. It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

One of the complicating factors is that obesity, which is closely associated with endometrial cancer, itself affects biochemical markers in the blood, making cancer-specific markers hard to find.

That’s why Blenkiron and her team are going straight to tumours donated to Te Ira Kāwai, the Auckland Regional Biobank.

“We’re going to use those tumours to look for molecules within the tumours that we can then hunt for in the blood,” says Blenkiron.

The molecules Blenkiron and her team are looking for are extracellular vesicles, tiny particles released by almost all living cells that aid in cell-to-cell communication. The vesicles released from cancer cells contain proteins with different molecular “fingerprints” than vesicles from non-cancerous cells.

“They’re like emails, a messaging system between cells, and they support the growth of cancer cells,” says Blenkiron. “We’re intercepting that process by squeezing these little vesicles out of the tumour tissue, identifying their protein cargos to then fish for those proteins in the blood.”

The study is the first in the world to use this technique to investigate gynaecological cancer biology and biomarkers. “We ultimately want to find a blood test we can use that will be affordable, accessible, easy to use, quick and that will be available equitably across New Zealand for improving early diagnosis and patient care,” says Blenkiron.

“It also allows us to trial something in one cancer type, and if it has success, we can apply it to another cancer type so we can help more patients.”

Blenkiron was also involved in a complementary study led by long-time mentor and colleague Andrew Shelling, professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, associate dean (research) at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and acting director of the Centre for Cancer Research.

His recently completed pilot study sought to learn more about the younger women diagnosed with endometrial cancer from both demographic and genetic points of view. The study participants had their tumours examined and parts of their genomes sequenced. The researchers hope that by better understanding both the genetics of the cancers and the women, they’ll be able to develop more targeted treatment approaches.

So far, the study has found that Pacific and Māori women are at higher risk of endometrial cancer, at a younger age, than women from other ethnic groups. A widely deployed screening test for endometrial cancer could therefore help improve health equity as well as individual outcomes.

The research has also found that younger women are more likely to have the endometrioid subtype of cancer, which is associated with high levels of oestrogen as well as with obesity, because fat cells produce oestrogen. The good news is that the endometrioid subtype tends to be less aggressive than others, resulting in a good outcome for most women who are diagnosed early enough.

“By looking at the tumour of an individual, we can identify specific genetic changes that might influce their treatment,” says Shelling. “This research is really looking into the future of precision medicine. Going forward, we might not treat people according to whether they’ve got endometrial cancer or breast cancer; rather, we might treat people based on the underlying mutations in their tumours. It gives us an opportunity to move away from chemotherapy, which kills every dividing cell and results in lots of side effects. This is the future of cancer medicine.”

Story by Karen Kawawada

Mātātaki|The Challenge is a continuing series from the University of Auckland about how researchers are helping to tackle some of the world's biggest challenges.

To republish this article please contact: gilbert.wong@auckland.ac.nz