Can we have our fish and eat it too?

31 March 2022

Can we feed the world and protect biodiversity? Here's a proposal for remaking global fishing.

Overfishing threatens a global catch that peaked in 1996 but perhaps a solution is possible.

The world can protect biodiversity and threatened species and also catch enough fish for humans to eat if nations cooperate on where fishing takes place, University of Auckland PhD student Tamlin Jefferson and colleagues say in a paper recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

Some big changes would be needed.

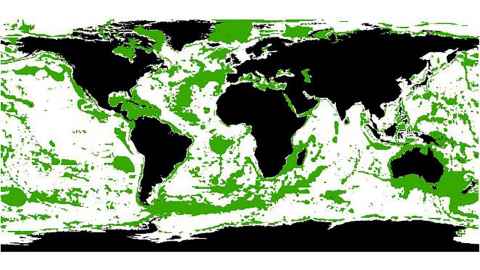

For example, most of the Tasman and the Caribbean would be off limits to fishing because they are biodiversity hotspots. At the same time, some big fisheries – such as Peru’s – would be unrestricted because they are crucial for food supplies and of lower conservation value. Fishing generally would be allowed in most nearshore places but not in places of exceptional conservation value such as the Red Sea and the waters around Australia.

Protecting almost 90 percent of biodiversity and threatened species would leave access to fisheries that provide almost 90 percent of catch, the scientists argue.

“From a conservation standpoint, protecting as much as possible is the ideal, but we've got to keep fish on the dinner table and fishermen and women have to pay the bills,” says Jefferson.

The study combined fishing catch data from the University of British Columbia’s Sea Around Us research initiative with information on threatened species and biodiversity.

“Our results add further support for calls to protect 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030,” wrote Jefferson, Dr Maria Palomares, of the University of British Columbia, and Dr Carolyn Lundquist, of the University of Auckland.

Currently, about eight percent of the world’s oceans is in designated protected areas, while only about three percent is fully protected from fishing.

A United Nations summit on biodiversity, the so-called COP15Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, will be held in China in April and May. The agenda includes the so-called 30x30 plan to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and 30 percent of the seas.

Almost all of the world’s fishing catch comes from inshore and continental shelf areas, with just 2.5 percent from the high seas. However, the scientists say a chunk of the high seas should be closed to fishing because of the rich biodiversity and number of threatened species.

Extending marine protection and fisheries management in the high seas is “imperative” for the survival of threatened seabirds and could bolster the prospects of the endangered southern bluefin tuna, the paper says.

While some small-scale fishing can be extremely destructive, such as tropical fishing using cyanide and dynamite, in general small-scale fishing is better than large-scale fishing.

“Continued access for small-scale fisheries is vital as they are typically more sustainable than larger fishing operations, use less destructive and energy-intensive fishing gear, use less fuel as they fish closer to shore, and discard less fish,” the scientists write. “Additionally, small-scale fisheries account for around half of all wild capture seafood and employ 90 percent of fishers and fish workers.”

Media contact

Paul Panckhurst | media adviser

M: 022 032 8475

E: paul.panckhurst@auckland.ac.nz