Dancing a fine line: women in Bollywood

3 August 2022

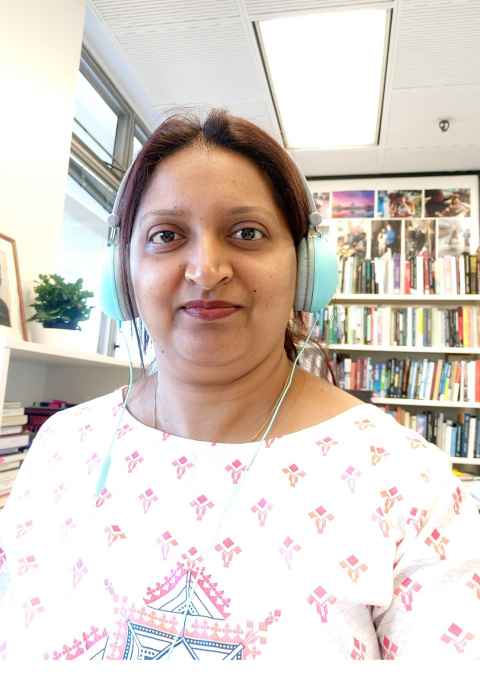

The changing position of female performers in Bollywood is the focus of University of Auckland doctoral candidate Kooshna Gupta’s research.

The most widely recognised Hindi language cinema of India, Bollywood is a multi-million dollar industry with huge cultural influence and popularity worldwide.

And the ‘item dance’, one of the main musical numbers of the film and almost always performed by a female dancer, has become increasingly important for its success and changed over time, says Faculty of Arts PhD student Kooshna Gupta, whose research covers films from 1988 to 2015.

“I’m particularly interested in the type of dance that is not related to the narrative but is more of an erotic display of women, just there for entertainment purposes. If you removed the song, in other words, the film would still make sense.”

She says women have often had very defined roles in these films, (referred to as ‘masala’ films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture, as they mix action, comedy and romance in melodramatic plots) which have to some extent reflected Indian society and its views on morality and propriety.

“I’ve not only looked at the characters played by female performers in that time period,” she says, “but also at the different dynamics of the actresses themselves, and acting as a profession in Bollywood for women.”

Kooshna says the traditional item song, from as far back as the 1950s and earlier, used to be performed by actresses who were often newcomers rather than established performers, and they were also never the heroine of the film, but rather the ‘vamp’ who could be seen drinking, smoking and being openly sexual in ways the heroine couldn’t.

“Because it wasn’t seen as acceptable in Indian society for the heroine to dance or be presented in such a provocative way in a public space,” she says.

“However, these actresses could become an instant success, so the item song was seen as a gateway to popularity. And as the Hindi cinema industry is so male-dominated, and one where women have a very limited role, you have some movies which would otherwise have been a big flop, but the item song saved the film; which of course gave these performers some power.”

And then she says film companies started spending serious money on the production of that one song because selling the rights to TV channels represented around 50 percent of their profits.

“And you started to see leading actresses, known for their other more ‘serious’ work like Priyanka Chopra, starting to perform these songs, which in turn increased the film’s budget, as they had to be paid more.”

We’re always going to have this tension between agency and subjectivity, but if you look at actresses in Bollywood, they have gained something; it’s a space, one place, where they are dominating, making a lot of money and becoming famous.

Add to that the cost of hundreds of people working behind the scenes – as musical directors, composers, choreographers, dancers, set designers, wardrobe, special effects and lighting – and the item song has become very big business.

Kooshna says there’s long been a paradox between the agency of the item dance performer and her power to earn money and fame, and the way she is achieving it; by performing in hyper-sexualised dances that objectify her for a largely male audience and create an unrealistic image of the ‘perfect woman’.

“We’re always going to have this tension between agency and subjectivity, but if you look at actresses in Bollywood, they have gained something; it’s a space, one place, where they are dominating, making a lot of money and becoming famous.”

However with increasing attention to rape and violence against women in India and the Nirbhaya case in 2012, several feminist movements and humanitarian organisations pushed for a ban on item songs.

As a result, Kooshna says the censor did at one point ban the songs from TV, but you still have YouTube channels playing 24 hours a day. However the fact that these performers are now considered professionals, like any other professional, is progress, she believes.

“So you can be in a serious film or a Bollywood film and cross genres as a female performer in India now. There’s a kind of flexibility to switch roles, from being a heroine to an ‘item girl’. I think that’s a positive thing.”

This is Kooshna’s second PhD, which she has now completed in the Department of Anthropology (ethnomusicology).

Her first combined her interest in linguistics and the Indian socio-cultural context by focusing on code-mixing; a linguistic term that refers to the use of more than one language, in this case Hindi and English, in the course of a single conversation or written text. She looked at Bollywood films from 2009 to 2014.

Media contact

Julianne Evans | Media adviser

M: 027 562 5868

E: julianne.evans@auckland.ac.nz