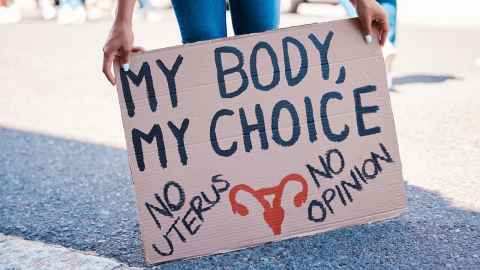

When abortion rights swayed elections

8 February 2023

Opinion: Dr Felicity Goodyear-Smith has worked as a certifying consultant at an abortion clinic for 40 years. The job, she says, was about making bad law work.

On Wednesday, 25 March 2020 New Zealand moved to nationwide self-isolation in response to the Covid 19 pandemic. Unless essential, there were to be no face-to-face primary care consultations.

I work full-time as a professor of general practice at the University of Auckland and by then my only clinical role was certifying consultant at an abortion clinic, assessing whether women seeking abortions had legal grounds, a role I have had since 1981. Fortunately, on that Wednesday I no longer had to worry about carrying out what can be sensitive consultations with women by video call or over the phone.

The day before lockdown the Abortion Legislation Act had come into force on Tuesday, 24 March. The Act decriminalised abortion, making it available without restrictions to any woman under 20 weeks pregnant. With that the role of certifying consultant had ceased to exist. Fortuitously, my job had disappeared after 40 years.

It was a job that was largely about trying to make bad law work, and a role established when a woman’s decision on whether to have an abortion was an issue that swayed elections and elected prime ministers.

In the 1970s, abortion was a crime unless there were medical grounds. Abortions were often approved only to preserve the life of the mother. Few women seeking abortions were able to get them. The first abortion clinic in New Zealand (the Auckland Medical Aid Centre, AMAC) opened in 1974, operating on the edge of the law – that a woman may suffer potential physical or mental harm should the pregnancy continue.

The anti-abortion Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC) sprang into action. SPUC’s moral crusade involved enlisting MPs as members, and a drive for mass membership assisted by the Catholic and other churches. Members attended rallies and wrote letters to their MPs condemning abortion as murder. SPUC leaders met with Prime Minister Norman Kirk in July 1974 to discuss legislation which would force the clinic to close. Kirk was an anti-abortion champion; his wife Ruth was SPUC’s patron. Kirk’s sudden death the following month did not deter SPUC.

Armed with affidavits from SPUC members, in September 1974 the police raided AMAC and seized all 500 confidential medical files. Women who'd had abortions were confronted by police at their homes or workplaces, often in the presence of family or colleagues unaware she she'd had an abortion. Abortionist Dr Jim Woolnaugh was charged with 12 counts of illegally procuring an abortion, where the police considered the grounds were social rather than medical. Woolnaugh was eventually acquitted in November 1975.

At the same time, a Labour MP and SPUC member Gerard Wall introduced a private member’s Bill to amend the Hospitals Act, restricting abortions to hospitals. Despite protest, this Bill was pushed through Parliament by Kirk’s successor Bill Rowling without the usual scrutiny by select committee, and was enacted in September 1975. By this time AMAC had purchased Aotea Hospital in Epsom, and continued to operate, despite protests, threats to staff, and arson attacks. The Act was so badly constructed it was subsequently declared null and void legislation.

Abortion was the key election issue in November 1975. Prior to the general election, SPUC conducted active campaigns against MPs who had voted against the Hospital Amendment Bill. Church congregations and the general public were encouraged to vote on the basis of the candidate’s attitude towards abortion. These tactics worked, and National Party leader Rob Muldoon, who opposed abortion, became prime minister.

Rowling had set up a Royal Commission on Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion in June 1975. Its hearings were dominated by SPUC, who employed Queens Counsels who aggressively interrogated pro-abortion witnesses, anti-abortionists received a relatively easy time. The Royal Commission’s report in November 1977 made a raft of recommendations aimed at reducing the number of abortions taking place. This formed the basis of the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act 1977, positioned within the Crimes Act.

Abortions were now more difficult to procure. Women seeking abortions had to see their doctor, two certifying consultants for assessment of their legal grounds, and then an operating doctor. An Abortion Supervisory Committee regulated these certifying consultants, and abortions could only take place in institutions licensed by the Committee.

For two years the Sisters Overseas Service helped women travel to Australia for abortions

The Committee refused to license the Aotea Hospital, and with the clinic closed, for two years, the Sisters Overseas Service helped women travel to Australia for abortions. The Committee struggled to appoint certifying consultants.

Doctors were confused about how to interpret the new law. SPUC doctors unlikely to approve any abortions were appointed, and consultants who certified too many abortions were not relicensed the following year.

After two years, AMAC was licensed and reopened. Slowly, public clinics were set up in main centres, and certifying consultants appointed who approved abortions on the grounds that a woman’s mental or physical health would suffer should her unwanted pregnancy continue. For 40 years, health providers found ways to make this bad law work. Pro-abortion groups such as the Abortion Law Reform New Zealand were reluctant to rock the boat, in case we ended up with a worse law.

In 2020, the law finally caught up with the view of abortion held by the majority of New Zealanders. Abortion, along with issues like homosexuality and euthanasia, became accepted as the decision of the individuals concerned rather than morally prescribed by the state.

Which is not to say that the issue had gone away. As recently as the leaders’ debate prior to the September 2017 general election, Labour leader Jacinda Ardern told anti-abortion Prime Minister Bill English that abortion should not be in the Crimes Act.

She and her government were as good as their word. The 2020 Abortion Legislation Act no longer falls under the Ministry of Justice; instead, it is in the domain of the Ministry of Health, where it rightly belongs.

Felicity Goodyear-Smith is a professor in general practice at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland. She is the author of From Crime to Care: the History of Abortion in Aotearoa New Zealand, launched on 9 February.

This article was first published in Newsroom.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland.

Media contact

Jodi Yeats, Media adviser

Mob: 0272026372

Email: jodi.yeats@auckland.ac.nz