Longer reproductive years linked to healthier brain aging

9 June 2025

A study of postmenopausal women pointed to a potential protective effect from estradiol, the most potent form of estrogen.

A new study suggests that the number of years a woman spends in her reproductive phase – between her first period and menopause – may be linked to how well her brain ages later in life.

Researchers analysed brain scans from over 1,000 postmenopausal women and found that women who had their first period earlier, experienced menopause later, or had a longer reproductive span showed signs of slower brain aging.

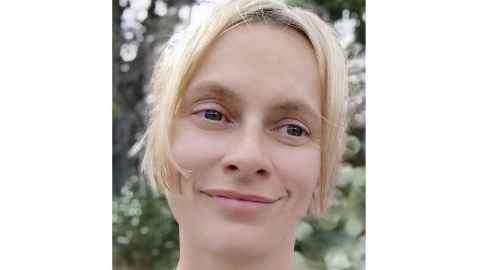

“These findings support the idea that estradiol – the most potent and prevalent form of estrogen during a woman’s reproductive years – may help protect the brain as it ages,” says lead researcher Associate Professor Eileen Lueders, of the University of Auckland’s School of Psychology.

The research may point toward the potential for health interventions such as hormone treatment in the years leading up to menopause and immediately afterward to combat an increased risk of Alzheimer’s for some women.

Estradiol levels rise at puberty, remain high during most of a woman’s reproductive life, and then decline sharply around menopause. This drop in estradiol has been linked to an increased risk of dementia and other age-related brain conditions.

Animal studies have shown that estradiol can help the brain by supporting neuroplasticity, protecting against inflammation, and improving communication between brain cells.

While this new study adds to the growing evidence that estradiol may play a protective role in brain health, Luders cautions that the effects were small, and estradiol levels were not directly measured. Other factors—like genetics, lifestyle, and overall health— also influence brain aging.

The co-authors of the research, published in the journal GigaScience, are Professor Christian Gaser, Dr Claudia Bath and Professor Inger Sundström Poromaa, scientists based in Germany, Norway, and Sweden. The brain scans supplied by the UK Biobank were biased toward individuals who were healthy, socioeconomically privileged, and white.

Lueders hopes future studies will include more diverse participants and directly measure hormone levels to better understand how estradiol and other factors contribute to brain health in women.

“It's encouraging to see research shedding light on how a woman’s reproductive years may shape brain health later in life,” says Alicja Nowacka, a PhD student at the University of Auckland. “As more women weigh the benefits of hormone therapy during menopause, findings like these spark important conversations and open the door to more inclusive, focused research in women’s brain health.”

Nowacka wasn’t involved in the study but has supported women navigating their treatment options, often in the face of conflicting medical guidance, she says.

Media contact

Paul Panckhurst | science media adviser

M: 022 032 8475

E: paul.panckhurst@auckland.ac.nz