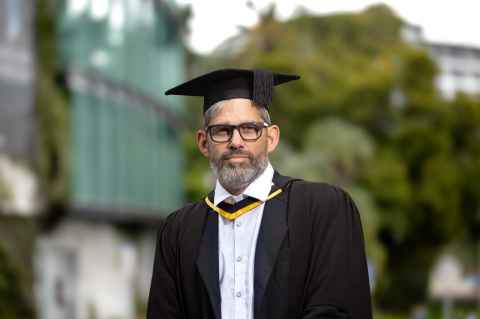

Zane Egginton: Weaving tikanga and technology for resilience

15 September 2025

Blending decades of design experience with a new understanding of mātauranga Māori, Zane Egginton's masters research helps communities prepare for natural hazards.

When Zane Egginton first stepped onto a marae four years ago, he felt the weight of uncertainty.

As a Pākehā researcher with English, Scottish, and Dutch whakapapa, he wasn’t sure how he would be received. He was about to begin a project that placed mātauranga Māori at the centre of resilience planning, and the responsibility felt immense.

"I’m not Māori myself, which was a little bit daunting at first because I didn’t know if I would be welcomed to do that. But that was not the case at all, the welcome I got was amazing," he says.

Zane has been part of Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland for more than a decade, teaching and supporting students as a technical team leader since 2014 and helping establish the University’s Design Programme in 2020.

On 9 September 2025, he graduated with first-class honours, capped with a Master of Design.

His research sits at the intersection of design, technology, and mātauranga Māori, exploring practical ways for communities to strengthen their resilience in areas prone to volcanic activity, floods, earthquakes and other hazards.

The work included using Geographic Information System (GIS) data to map hazards and climate risks, developing a marae numbering system to provide a consistent framework for identification, and exploring Extended Reality (XR) to support storytelling and retain Māori knowledge about past hazards.

The project contributed to Professor Anthony Hōete’s Ngāti Awa Atlas of Marae Resilience.

"Anthony has done a lot of work in how Māori see the world, and how it radiates out from the marae and hapū level, out to the Iwi and wider again, and how we translate that into an atlas," says Zane.

"He basically outlined that if you wanted to do this as a research project, that would be really good."

Zane’s expertise lies in mapping and modelling, interrogating data, and visualising risks to make information more accessible. He says the atlas project was a real opportunity to contribute his skills to a local community, and work alongside Māori.

"It’s always been my belief that Māori have had no choice but to learn a lot from Pākehā, and it’s been a one-way street. Pākehā are only really just learning about Māoridom now," he says.

One of those experiences was learning the tikanga for meeting on a marae, which can vary between Iwi and hapū.

"Right down to how you meet, who’s in that meeting, and how you address each other, it was an incredible experience learning that."

Zane’s masters degree comes nearly two decades after his Bachelor of Science and years of work in design and technical roles across academia, film, television and live events. At 51, he says returning as a student gave him a fresh perspective.

"It’s quite a different experience doing your masters later in life, because you’ve got all this knowledge, you can align your own experiences with academic theory and case studies, you can relate to the course material and it actually makes sense," he says.

"It’s influenced a little bit on my decisions around how these places get designed and resourced, and I have a really good rapport with masters students now because I’m like, 'I know what you’re going through, I’ve done that class, I’ve been there'."

Pursuing the degree required some sacrifices – time off work, late nights, long weekends, and a lot of understanding from his whānau. Zane says surfing with friends helped him maintain some balance.

"For some reason, for me, that looked like getting up at 6am on a Saturday in the middle of winter, getting into a wet suit, and jumping into the ocean. It just grounds you, and there were people down in the Bay of Plenty who surfed as well, including people who were really high up in the Iwi, so it was an asset having those ways to connect."

The outputs of Zane’s research will be gifted to Ngāti Awa, something he describes as both a responsibility and a privilege.

"It’s their research as well, they have as much ownership over what I found as I do," he says.

While all the GIS data Zane worked with was publicly available, the atlas itself was co-authored with hapū members to ensure the work reflected both technical methods and local knowledge.

"Some of these stories that were coming out of the landscape were of past events that were not visible when you stand on the ground, of where previous floods had been, where the river used to flow, where you couldn’t build some things, their ancestors knew that," he says.

"It wasn’t just about ownership of facts and figures, but ownership through collaboration, talking to people and including them in the work. That whole structure was around Māori data sovereignty.”

Reflecting on his experiences, Zane emphasises the importance of culturally respectful collaboration.

"It’s important, especially if you’re working with Māori or working in New Zealand, that you consider these things. It’s not difficult, it’s not a barrier, and often opportunities come from that. You’ll get a much better outcome if you work with Māori and respect those rights."

Media contact

Media adviser | Jogai Bhatt

M: 027 285 9464

E: jogai.bhatt@auckland.ac.nz