New traffic charges could backfire, expert warns

28 January 2026

Traffic congestion charges won't work unless realistic alternatives to driving to work are available, says University of Auckland’s Dr Hyesop Shin.

Time of use traffic charges can work wonders, but only if public and active transport options are improved, says University of Auckland’s Dr Hyesop Shin.

A lecturer in environmental science, Shin says new legislation allowing councils to introduce congestion charges has the potential to reduce vehicle use, traffic jams, air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions.

“Congestion has so many harmful impacts, because lots of emissions are produced while vehicles pile up.

“However, congestion charges could increase emissions, if people take detours and end up driving longer distances to avoid toll points.

“To avoid this, better public transport and active transport pathways need to be available, so people have realistic alternatives to driving,” he says.

Shin is providing research for Auckland and Wellington City councils on the potential impacts of different congestion charging schemes.

His team has just completed a study of Auckland traffic and how it might change under a charging option using a cordon around the central business district.

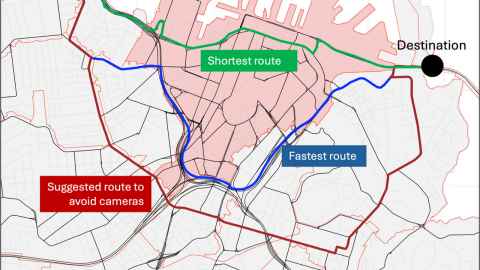

Computer modelling suggests if the cordon around the city centre is imposed, some drivers will take longer routes to avoid paying, he says.

“If the charging system doesn’t anticipate drivers taking detours to avoid charges, it could create new bottlenecks, increase noise and emissions in local neighbourhoods, and push traffic onto roads that haven’t been designed for heavy traffic.

“The council will need to monitor areas near toll points to make sure diversion hotspots aren’t having harmful impacts on people’s health, through air pollution and noise in residential areas or near schools,” says Shin.

Auckland Council is weighing up six different options for setting congestion charging points, focused on the city centre, highways leading to the CBD, or a combination of both.

Using computer modelling, Shin’s team aims to predict how people from different ethnic groups, ages, genders, and neighbourhoods might be impacted by different charging schemes.

“We plan to map how proposed charging scenarios might shift traffic patterns and affect transport accessibility in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas.

“I’m concerned that the charges have an equitable impact and don’t place an extra burden on people living in areas with higher deprivation.”

He predicts people from wealthier suburbs might just pay congestion charges and continue to drive cars into the central business district for work or education.

However, lower income workers might face significant impacts from the charges if they don’t have public transport available from the areas they live in.

Some might choose different work shifts, or park outside the city and walk or bus in, he says.

Done well, congestion charges could encourage more people to take public transport and cycle, scooter or walk to work, says Shin.

“If more people are exercising while travelling to work or places of education, that will have significant benefits for their health.”

The study found travel to the Auckland CBD took about 50 percent longer at peak times on Tuesday to Thursday mornings and evenings.

Mondays are slightly faster flowing and traffic eases off on Fridays, reflecting a shift to more people working from home on these days.

More vehicles hit the roads on rainy winter days, adding to traffic jams.

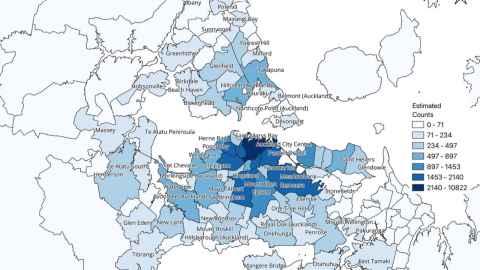

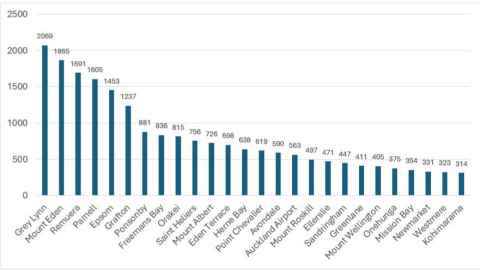

Most morning peak traffic comes from suburbs immediately surrounding the city centre, such as Grey Lynn, Mount Eden and Remuera.

“Many residents in these neighbourhoods travel a fairly short distance into the CBD, but it creates severe traffic jams some mornings,” says Shin.

High numbers of vehicles travel from South Auckland into the CBD on Tuesdays to Thursdays.

State highways from the west and north are also busy, but the traffic intensity is lower than from the inner-city suburbs.

The team is looking at different international examples of traffic congestion charges, to gauge what works best.

New York provides a relevant example, with a $US9 charge between 5am and 9pm decreasing traffic by an average of 11 percent over six months, says Shin.

The team's research has been funded by the University's Transdisciplinary

Ideation Fund and Emerging Researcher Network Seed funding.