When every second counts

19 October 2018

The stroke unit at Auckland City Hospital is one of just a few centres in the world – and one of the most active – in implementing a new treatment that is preventing deaths and transforming lives for people who have strokes caused by clots.

To an economist, time is money.

To Alan Barber, Neurological Foundation Professor of Clinical Neurology at the University of Auckland, time is brain cells.

When a clot prevents oxygen from reaching a part of the brain, “two million cells die every minute,” says Alan. So when a person has an ischaemic stroke, speed is of the essence.

In New Zealand every year 9,000 people have a stroke. Of these, 2,000 are of working age, some in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

There was a time when little could be done for those who suffered a stroke, except “good nursing”, says Alan, plus physiotherapy and speech language therapy to promote recovery.

That was true 20 years ago when he left Auckland to do his PhD in neurology at the University of Melbourne. But now the situation is very different, thanks to a large international study in which he has played a role.

Research Alan took part in during his four years at the University of Melbourne before he returned to establish the stroke unit at Auckland had focused on developing drugs to dissolve the clots that caused the strokes. These proved successful in breaking up or dissolving some of the smaller clots, but could frequently not dissolve the larger ones that can be more than a centimetre long.

The recent international study has succeeded in overcoming that problem through a series of controlled international trials, with patients from New Zealand taking part, in which a new procedure for retrieval of large clots has been shown to be effective.

“This is an amazing procedure, which has transformed the practice of neurology over the last three years,” says Alan. “We are treating people who suffer the biggest strokes that anyone can survive. A lot of these patients wouldn’t have survived. And if they had, many would be needing 24-hour care.

“For every five of the people we treat, one goes home completely normal.

For every three people we treat, one is significantly better. Now, ‘better’ may be going from private hospital care to being able to live in a rest home and use a walking frame. Or it can be the difference between living in a rest home and living at home with someone coming in to help. Or it can mean being able to go back to work.”

So what is the new treatment and how does it work?

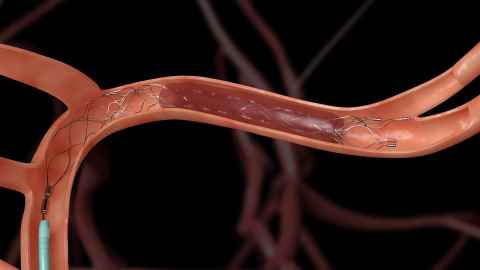

Described by Alan’s colleague, neuroradiologist Dr Stefan Brew, as more like plumbing than rocket science, the procedure requires a retrieval device which looks a little like wire mesh. The device is fed (on the end of a wire) into the femoral artery and up into the brain. There it slides through the clot (which has the consistency of jelly) and once fully through, it is opened up to gather the clot and draw it out, with the help of suction.

“The sooner you can do it, the more of the brain you can save,” says Alan. “But it takes a while for people to get to a hospital, have a brain scan, have someone like me go down to see them in the emergency department, and then be given a clot-busting drug or a clot retrieval.

“Our average time from onset to doing this is about 3.5 hours.” Which is very impressive since his team takes patients all the way from Taranaki in the middle North Island and from Kaitaia and beyond in the far north, as well as from the local Auckland hospitals and all those in between.

The current phase of the research involves implementation, says Alan.

One focus is on managing the patient during and after the procedure, including looking at the efficacy of different techniques of anaesthesia.

If we can cut another ten minutes from the procedure somewhere, that means saving 20 million brain cells for the patient.

Another is on logistics of a highly-complex kind: the speeding up of the whole process from the time the first symptoms appear to the arrival of the patient in the operating theatre, with the team scrubbed up and ready to go.

“This means changing the behaviour of people and systems,” says Alan. “We can’t do this treatment unless people get into hospital fast.

“It is a brand new treatment being done by a relatively small number of centres around the world, so it is important to report for the rest of the world on how much of this work we are doing, how long it is taking, and how to treat people more rapidly. We’ve just submitted a paper for publication noting the New Zealand experience.

“We need to look at where there are problems or delays,” says Alan; though he adds that there is also a lot to learn from the successes.

“Recently we had a patient who had a stroke in the middle of the North Island. The patient got to the local hospital, had a brain scan to exclude the bleeding type of stroke, then got started on the clot-busting drug and was taken by helicopter to Auckland. The procedure was started within two and a half hours of the symptoms coming on, which was miraculous. So it is helpful to do research on how that happened. What did they do right? If we can cut another ten minutes from the procedure somewhere, that means saving 20 million brain cells for the patient.”

Alan, who is deputy director of the University’s Centre for Brain Research, is very grateful for the philanthropic support he has received throughout his career to enable this research. This has included the Chapman Scholarship from the Neurological Foundation of New Zealand, which supported him through his PhD in Melbourne, the payment of half of his salary by the Julius Brendel Trust when he returned to Auckland to set up the stroke unit, and further support from the Neurological Foundation, which funds his position as Neurological Foundation Professor of Clinical Neurology at the University, as well as funding two research fellows.

From a patient's perspective

Rupert Myhre is very grateful to the friend he was with when he woke around 5.30 in the morning to discover he had “had some kind of seizure,” fallen out of bed and was feeling dizzy and disorientated – even to the point of falling again.

“I was trying to tell myself I’d be OK soon, though my brain was telling me something was terribly wrong,” says Rupert.

“Luckily my friend was there and had the good sense to call an ambulance immediately.

“I remember getting into the ambulance, though I don’t remember arriving at Waikato Hospital, where I was given an immediate assessment and diagnosed with a stroke.”

He has no recollection of travelling by helicopter to Auckland Hospital, and discovered only when he woke a little after 11am that he had been treated for a stroke and had had a clot removed from his brain.

Rupert, who is 31 and had had no warning of the stroke, is one of the lucky ones. A week after the procedure he was back at home. Seven weeks later he was travelling with his sister in Asia. And now, another two months down the track, he is already back at work part-time – though now on life-long medication and “still recovering”.

Without the treatment, Alan Barber told him, he would have had just a one-in-four chance of living independently.

Alan is keen for as many people as possible to know the first signs of stroke as this may save someone’s life. Just remember ‘FAST’. Is there drooping of one half of the Face, is one Arm weak, and is there any Speech difficulty or slurring. At the first onset of any of those symptoms it’s ‘Time to act and call an ambulance’.

By Judy Wilford

Ingenio: Spring 2018

This article appears in the Spring 2018 edition of Ingenio, the print magazine for alumni and friends of the University of Auckland.