Creativity helps kids get through pandemic

20 April 2022

World Creativity and Innovation Day: Drawing-based research finds children use creative activities to cope with lockdowns.

While children’s drawings show they have used creativity and play to cope with lockdowns, they could have suffered less if their needs had been considered in public health decisions, a researcher says.

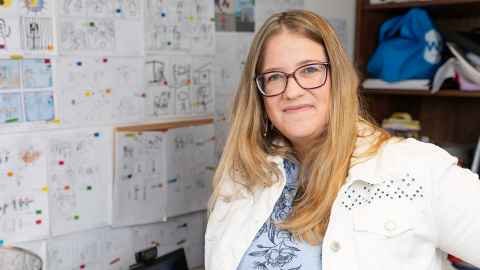

Working for the University of Auckland’s School of Population Health, Dr Julie Spray has used comics, drawn by or with 26 children aged 7 to 11, to elicit their experiences of pandemic public health measures, including lockdowns, over the five months from November 2021 to March 2022.

“Comic-making worked exceptionally well as a research method,” Spray says. “If you're doing an activity with a child, you're talking while you're doing the activity, it takes a lot of the pressure off for a kid who is talking to a stranger for an hour.”

Spray also supervised a summer scholar, Samantha Samaniego, to review how children have been represented, included or excluded in Covid-19 public health promotion policy, media and messaging.

The resulting report has just been published online, along with a gallery of children’s comics. See The Pandemic Generation and comic gallery.

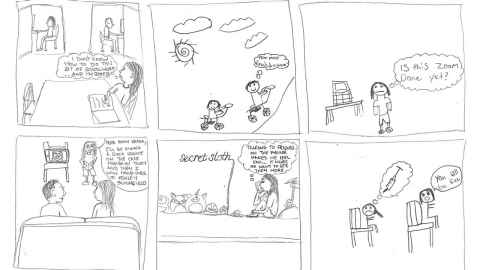

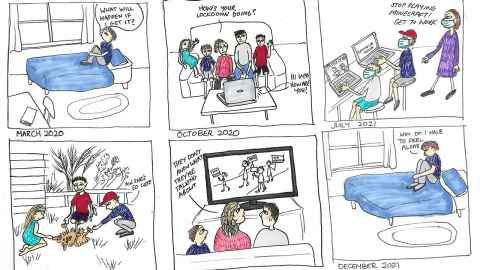

The comics and illustrations show readers, whether they are participants, families or policy-makers, how the pandemic looked through the eyes of 26 children from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and suburbs across Auckland.

“After the initial disruption of ‘what I thought was going to happen tomorrow suddenly isn't happening tomorrow, and it's really disconcerting to realise that what I thought I could predict I actually can't,’ then they just settled into lockdown,” Spray says.

Many of the children could only remember life during the pandemic and found it difficult to answer questions about it. “It felt like asking the fish to comment on the water, where the pandemic was the water and they didn't have enough time on Earth to realise you're not supposed to be swimming in water,” Spray says.

That’s where drawing helped elicit their experiences, such as one nine-year-old who drew about playing Lego and watching Star Wars with her brothers, and the excitement of going to the dairy.

On her birthday, she was allowed to have one friend visit at a time through the day.

“What was strange had become normal to these children,” Spray says.

However, children still found lockdowns tedious and annoying and lonely.

Ananaya drew lockdowns as a picture of herself in jail. She said “it’s like your whole world is your house.”

Through her research, Spray found children used creative activities as a way of coping.

“They've created their own businesses or made rafts out of bottles. But that is how they've accommodated this thing and what helped them get through,” Spray says.

“In their own creative and innovative ways they've coped with their loneliness and isolation and boredom.”

But this doesn’t mean we should rely on children’s creativity to get them through unscathed and forget about supporting and including them.

Spray noted found that, in weighing up the costs and benefits of public health measures, the needs and views of children were excluded.

“There was so little concern about children and children’s perspectives – not from politicians, not from the media. There was a lot about how ‘at risk’ children might be, but not a lot about ‘what matters to kids during this time?’”

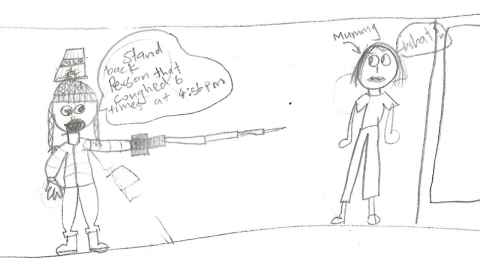

Children were weighing up risks, just as adults were, but using episodic information, such as YouTube ads and the 1pm briefing, that wasn’t designed for them.

“A lot of them talked about case numbers, but then they had to interpret those case numbers and decide ‘what does this mean for me?’ And we haven't given them the context and the tools to be able to do that.

“If cases got to be 100, they would get really really worried, because they have no sense of how many people are actually in the community. They don't have that sense of scale. They don't really know what 5 million people is. So 100 cases, sounds like a lot.”

Children were often overestimating risk, Spray found, and feeling anxious and worried.

Saara, aged 10, created a six-foot Germasword to keep others at bay.

And in weighing up pros and cons of public health decisions, children’s needs were ignored.

“For example, did playgrounds need to be closed once we knew surfaces were poor transmitters of the virus and the real risk was aerosols,” asks Spray.

Spray’s review of public health decisions found the “public” was perceived to be adults, generally middle-aged adults. Children were perceived as “public in waiting”.

However, children were an essential part of the public health response, needing to wash their hands, wear masks and get vaccinated to protect other members of the “team of five million”.

Further, they were frequently agents of public health, reminding parents to wear masks or scan in, requesting vaccinations and taking measures to keep themselves and others safe.

In noting the reliance of policy-makers on parents to convey public health

information to their children, Spray says including children in public health decisions and communications would ease the burden on caregivers, too.

Friends are very important to children, and, while adults could instantly connect with friends using devices, children didn’t usually have mobiles, had screentime restrictions and had to give up use of devices so adults could do their work. The digital divide impacted children, Spray says.

In her report, just published, on children’s experiences of the pandemic, the Government and other decision-makers would appear to get a poor grade and a comment: “Could do better.”

- Read: The Pandemic Generation

Media Adviser

Jodi Yeats

M: 027 202 6372

E: jodi.yeats@auckland.ac.nz