Can we fix democracy?

9 June 2022

The world faces ‘democratic recession’. Today more people live in autocratic regimes than in liberal democracies. Matheson Russell says democracy needs re-shaping to meet the challenges of climate change and rising inequity.

When it comes to the state and future of democracy, the think tanks, global policy experts and journalists are pessimistic.

“The world is becoming more authoritarian as autocratic regimes become even more brazen in their repression,” was the pronouncement of the Stockholm based international Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), at the launch of their Global State of Democracy Report 2021.

The Economist has taken a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide since 2006. Their 2021 report The China challenge, found that fewer than half of the world’s population live in a democracy of some sort, and even fewer 8.4 per cent in what it regards as a ‘full democracy.’

Out of 167 countries The Economist looked at, 75 could be considered partly democratic, with, a growing number of 57 ‘authoritarian regimes.’ The report produces a Democracy Index to distil its research. In 2021 it was 5.37 and has been in decline since the global financial crisis of 2008. New Zealand continues to rank well, second after Norway and ahead of the Nordic states that consistently populate the top 5.

The Pew Research Centre asked people in 17 advanced economies what worried them about their democratic political system. More than half, 56 per cent, said their political system needed major change or needed to be completely reformed. About half of those polled in eight of the 17 countries said their political system needed change but they also had little or no confidence the system could effectively be changed.

Matheson Russell is a philosopher and Associate Professor in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Auckland. He says, “When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, we were told it signalled ‘the end of history’. The Cold War was over, the Communist cause had been defeated. Liberal democracy had won the day.”

Thirty years later that optimism has been dispelled. Democracy, he says, faces enormous challenges. From climate change to economic inequality, from the splintering of mass media to the rise of disinformation and extreme political polarisation. The voter turnout in major democracies keeps falling, matched by polls recording low satisfaction with governments across the globe.

It has not taken long, he says, for the ‘the end of history’ and the triumph of liberal democracies to become a period of ‘democratic recession’, a phrase coined by political scientists.

Under our noses, democracy is being reimagined and redesigned around the edges of existing democratic institutions.

Russell offers a counterpoint to the narrative of gloom. “Under our noses, democracy is being reimagined and redesigned around the edges of existing democratic institutions.” A re-imagining of democracy is evident, he says, though rather than a rapid blooming it is more like the first, fragile shoots of spring growth. Citizen-led decision-making processes are being experimented with to try to counter the loss of engagement by ordinary people in the way decisions are made.

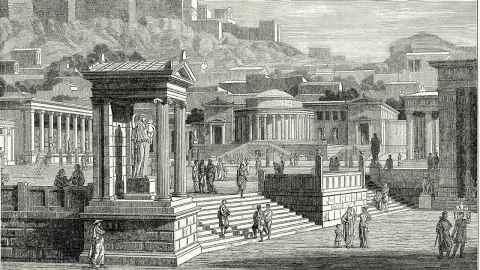

They are, he says, based on sortition, an ancient practice from the cradle of democracy when Athens was a city state from 600 BC. Russell explains: “Sortition or lottery was a central feature of ancient Athenian democracy. In Athens all citizens were able to participate in the business of politics. In particular, the ecclesia, or plenary assembly, was open to all citizens.”

But the ecclesia was not a law-making body. The role of the ecclesia was limited to debate on certain pre-determined issues. Most of the business of political decision-making took place in other bodies: including the Boule – the 500-member governing council – which set the agenda for assembly meetings, the Nomothetai – the legislative body – and the Dikasteria – the courts – each of which involved hundreds of citizens.

Citizens were not elected to these bodies. Each year, a panel of about 6000 citizens was randomly selected. From this panel, individuals were chosen by lot to become members of these bodies for a term. “In this way, the lottery system meant that citizens would rotate through political offices over the course of their lives,” he says.

Renaissance Italian city-states like Florence also used lotteries in some parts of their political systems, making random appointments to law-making and other bodies. The Florentines saw the lotteries as an essential tool to prevent factions from manipulating the political process. It was a means to protect the integrity of politics against concentrated power.

Abortion law reform

In 2016, the Irish Government gave sortition a trial. Ninety-nine randomly selected citizens, a cross-section of society, were selected to consider the contentious issue of abortion law reform. Over a series of weekends across several months, this Citizens’ Assembly interviewed experts, heard first-hand testimony, weighed medical, moral and legal considerations, deliberated together and finally drafted and voted on a set of recommendations.

Politicians, who observed the assembly’s deliberations were impressed by the rigour of the process and the quality of the recommendations. In 2018 the abortion laws were liberalized through a referendum and an amendment to the Irish constitution.

Russell says, “The Irish public were able to see people like themselves conscientiously working through a matter of complexity and gravity. And, ultimately, the work of the citizens’ assembly was instrumental in moving Ireland forward on a politically deadlocked issue.”

Referendums are sometimes touted to give citizens a say in contentious political decisions in New Zealand. However, Russell says, a common issue is a knowledge gap. How can voters reach an informed view on what is often a difficult moral and ethical choice? A model that is working well has been introduced as a standard part of the process in the American state of Oregon.

Before a referendum a random sample of between 18 and 24 citizens, selected to be representative of the population, are asked to consider the ballot initiative in depth. They agree to meet for three to five days to learn about and deliberate. As part of the process, they interview proponents and opponents of the ballot proposal.

Their research is summed up in a Citizens’ Statement, which is sent to all voters with the ballot papers. The Statement is a one pager that explains what the ballot initiative is, and summaries the main arguments pro and con. The Statement reports on how the Citizens Review panel intend to vote. This has been a permanent part of the process in the Oregon legislature since 2011.

Digital participation

Iceland has taken what has come to be called participatory democracy even further. Iceland, says Russell, faced political turmoil following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. Following public pressure, the Parliament agreed that the Constitution of Iceland should be completely rewritten.

A coalition of activists, scholars and community leaders came up with a novel process. A key component was a National Assembly comprised of 1500 randomly selected Icelanders. The Assembly used crowdsourcing as a way for the wider public to contribute ideas for a new constitution.

The next stage saw 950 randomly selected Icelanders appointed to a National Forum, facilitated by Anthill, a coalition of academics, politicians, and community leaders, representing civil society. From there Iceland held an election for 25 citizens to form an assembly to draft the new constitution, encompassing the work of the previous bodies.

The reshaping of the Icelandic constitution combined sortition, election, crowd sourcing, digital participation, and referenda. The result, notes Russell is the most inclusive constitution in history that include radically new ideas, like the nationalisation of previously unowned natural resources, the right to access the internet and the right of citizens to initiate referenda on existing law.

Russell says, “The entire process met with opposition by the pollical establishment. They resisted putting the draft constitution to a referendum. When it did go to a referendum in 2012 it was supported by two thirds of Icelanders.”

The Iceland experiment shows how narrow our imagination of democracy is.

The political establishment were ultimately successful in preventing the new constitution being passed into law. Russell says, “Be that as it may, the Iceland experiment shows how narrow our imagination of democracy is.”

He cites Yale political scientist Hélène Landemore who observed the Icelandic constitutional drafting process in person. In her recent book Open Democracy, she writes: “The Icelandic example … emboldened me to conclude that the limits of our current systems, as well as the changes brought about by globalization and the digital revolution, call for a radically different approach to the question of the best regime—one that interrogates the very institutional principles of democracy as we practice it today.”

Russell says these examples offer lessons for the evolution of liberal democracies. “Randomly selecting people to make important decisions might seem a bit crazy, but what we have learnt from experience is fascinating.”

The big issues societies face need experts, but lay people can handle complexity. “Ordinary people are perfectly competent to make complex decisions if they are given the opportunity, the context, and resources to do it.”

Research shows that citizen assemblies often analyse issues with more depth and nuance in the debate than in parliamentary committees and assemblies and understand the competing goals and trade-offs better. It is possible to gain bi-partisan consensus on contentious issues like taxes and environmental protections.

Russell says, “The more information people are given the more convergence they display. And values overlap more than you might imagine.”

The difficulties, the loss of confidence and the rise of public cynicism in modern democracies suggest new approaches and ways of thinking are needed. Russell says, “The democracy of tomorrow could plausibly look very different to the model of democracy we have inherited.”

For citizens in democracies across the world, the challenge, says Russell is to employ our intelligence, creativity, and advocacy to ensure that the democracy of tomorrow is the kind of democracy that we need: fair, inclusive, forward thinking, and properly equipped to tackle the challenges we face.

This article is based on a talk by Associate Professor Matheson Russell for Raising the Bar Home Edition 2022. The full talk is on RNZ: How democracies could become more, well democratic.

Mātātaki|The Challenge is a continuing series from the University of Auckland about how our researchers tackle some of the world's biggest challenges. Challenge articles are available for republication.

Contact: Gilbert Wong gilbert.wong@auckland.ac.nz