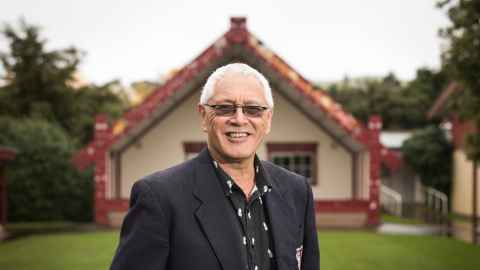

Changemaker: Professor David Tipene-Leach

12 June 2023

Aotearoa is still plagued by health inequities amongst Maori and Pacific patients, but Dr David Tipene-Leach has found ways to change this.

In this interview with Dale Husband for E-Tangata, Professor David Tipene-Leach (Pōrangahau, Ngāti Kere and Ngāti Manuhiri) reflects on his 40-odd years as a doctor, the progress he’s seen throughout his career, and the steps that need to be taken to make health equitable for Māori and Pacific people. This piece previously appeared on E-Tangata and is republished with permission.

Kia ora, David. It’s a pleasure to have you as a guest on E-Tangata. I understand that you and your two sisters Deanne and Jennifer, like me, have a Pākehā dad and a Māori mum. And your full name is David Collins Tipene-Leach.

Yes, that’s right. Mum is the Tipene. She’s Ngāti Kere from the Tipene-Matua family of Pōrangahau. And my dad is a Leach, so I ended up as a Tipene-Leach.

Tēnā koe. Now where do you fit in your family?

I’m the oldest of us three kids. In fact, at 67, I’m the oldest of our 60 or so cousins. Mum, Te Rangi Kauia, is one of 15 siblings.

And what can you tell us about your school days?

Well, both my parents were teachers. And, as is the way with teachers’ kids, we grew up all over the place. My father, Collins, was in the army as well and we spent some time in Malaya, during the 1960s. Then we came back to New Zealand, and we moved to Ōkato in Taranaki, and that’s where I spent my early and late teenage years.

Where did your interest in medicine come from? Were you always going to be a doctor or were you expected to be a teacher?

Apparently, I was always going to be a doctor, although I don’t quite recall making that decision. But what I do recall is that my grandmother, Tina (short for Ernestine) Hine-i-taria Tipene was a kind of role model.

She was a deliverer of babies, a midwife, but not trained. She was the first-aid person everywhere you went. She was the ambulance driver. She was kind of everything medical and everything sort of social. And I’ve now got it fixed in my mind that she was probably the one who prompted my interest in doing something similar. So I ended up being a doctor.

I recall, though, when I was a teenager, it was the 1970s — the time of Ngā Tamatoa and the Polynesian Panthers and feminism and all the “isms” and all the big changes. Things were happening in those times, and I distinctly recall my response in my application for medical school when they asked: “Why do you want to be a doctor?” And I said it was because I wanted to “make change”. So I guess that I didn’t say something routine like “I want to help people” or “I want to do good things”. I just wanted to change stuff.

I used to look around and see what was happening in cities, in Auckland. Especially with young Māori people getting into trouble. Things not going well. And, hey, how come we’re always the poorest in town? Yeah, I recall wanting to make change.

You went through varsity and then to med school? David, was this before MAPAS (the Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme), or did that feature later on? I understand MAPAS kicked off in 1972.

I was in either the fourth or the fifth intake of the Auckland medical school. That was in 1973 — and I always thought that I was a MAPAS student.

I certainly applied to MAPAS and I’d thought that I was a MAPAS student for half my life. There were three of us there who thought we were MAPAS students. That was me and Pauline McPherson and Sam Fuimaono.

Anyhow, years later, I found out that there’d been only two MAPAS places in my year. And, seeing that I got the highest mark of us three, I guess that I was the one who wasn’t a MAPAS student.

But, either way, in those days, we were proudly MAPAS students. There were so few Māori or Pacific students. We felt we had the “future of the people” on our shoulders. We stood out — and we were determined to do well.

Apparently, I was always going to be a doctor, although I don’t quite recall making that decision. But what I do recall is that my grandmother, Tina (short for Ernestine) Hine-i-taria Tipene was a kind of role model.

There was some resentment from some sectors of our community who thought MAPAS was making it an easier run for Māori and Pasifika applicants — even though all the students had the same exams to pass on their way to qualifying as doctors.

I’m aware that it caused some controversy later on. I went back in 1987 and taught at the med school in Auckland. In fact, I think I was the first of the graduates to go back and teach there. And, by that time, it was quite controversial. There were five or six places at the time and the numbers had begun to concern the middle to upper-class people who were trying to get their kids into medical school.

I don’t recall it in my time as being a problem because, in effect, there were almost no Māori doctors, no Māori medical students. There was one in each of the two intakes ahead of us. And there was either one or two in the years after us.

There weren’t enough Māori students to make any difference to other people getting in. And that’s probably why it wasn’t an issue. It became an issue later on because, as the numbers became more significant, other people started missing out. That’s when people started to complain and talk about Māori privilege and those sorts of things.

Nothing’s really changed in the sense that we still need more Māori medical professionals, don’t we? The challenge is still ahead of us?

Yeah, the medical schools have done a marvellous job. We now have equitable numbers of Māori and Pacific students going in. But because we have so many years of too few graduates, we’re still poorly represented in the medical profession.

And it’s going to take years before this large group of Māori and Pacific doctors, who are now coming through, are well-established and are the leaders of clinical teams and the managers of hospital systems and primary care systems. So it’s going to take a long while for that influence to be hugely significant. But it’s a great start.

Tēnā koe. A lot of med students aimed to become GPs. That was their goal and I suspect they stayed in that line of work. But you’ve had a variety of roles in the medical profession over the last 40 years or so.

Well, I was a house surgeon in Middlemore Hospital in my first year out, and after that I partnered up with Puhi Rangiaho from Rūātoki, and in my second year we went back to Whakatāne Hospital where I was a year-two house surgeon.

It was great. I really enjoyed being a house surgeon. Then I applied to be the medical registrar but they gave that job to a South African who was a nice bloke. I always thought that was kind of interesting — you don’t take the local Māori person who’s applying, but you do take a South African who’s coming into the country.

Then I got a call from a GP, Dr Tom Kawe, who’d had his practice in Whakatāne for 40 years. He had 4,000 patients and he told me he’d watched me over the year and felt that I should take over his practice because he wasn’t well and I “sounded like a good chap”.

So I went into this huge practice as a third-year doctor. Fortunately, the nurse stayed on for six months, as she said she would. And she kind of taught me how to be a GP. It was great. I didn’t know about GP training back then.

I was thrown in the deep end in many ways. But I quickly realised that the things you didn’t know could be looked up in a book — and that forming relationships with people and understanding their needs were the important elements of general practice.

I did that for three years. I didn’t make any money. I didn’t have wealthy patients. In fact, I didn’t charge anything. I just got the GMS government money — that’s the subsidy paid to GPs to help reduce patient fees.

I remember being paid with sacks of puha and sides of pork and mussels and what have you. And this was all because I was still a young, fresh, anti-capitalist, anti-sexist, anti-racist thinker of the '70s who knew nothing about business or about money.

I thought everything would be fine without money, so to speak. But everything fell to bits and real life caught up with me. Then I spotted, in the paper, an advertisement for public health medicine. It was called community health in those days. You’d do a one-year diploma course and then work a further training period to be a specialist. And so I applied and I got in. I thought community health sounded like me — remember, I wanted to “make change”.

One of the things that’s made my life as a doctor interesting is that I’ve been able to change the roles I play as a doctor. I was a hospital doctor, then a GP, and then into community health.

I did that year of training in Wellington, and then we moved to Auckland and did further community health specialist training up there. As part of that, I joined the medical school in 1987 and began teaching Māori health.

We now have equitable numbers of Māori and Pacific students going in. But because we have so many years of too few graduates, we’re still poorly represented in the medical profession.

I had some background in trying to think through how poorly the health system served Māori. I had written about it. I wrote a paper called "Maoris: Our feelings about the medical profession". I think the only other person who was writing anything of that nature at the time was Mason Durie.

That evolved into a chapter in a 1981 textbook on general practice, which was pretty cool. And so was being the first lecturer in Māori health.

Three years later, after I became a community medicine specialist, I got a chance to work for the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa in the remote Pacific Basin Medical Officers Training Programme.

I was based in Ponape (aka Pohnpei), a little Micronesian island of the Federated States of Micronesia. It had a medical school with 60 Micronesian students and a dozen teachers. New Zealanders, Australians, English, Americans, a Fijian and a Korean.

And the system was that, if you passed year one, you got to be a health assistant. If you passed year three, you got to be a medex. And, if you passed year five, you got to be a medical officer. It was a great little system. These students had probably no more than a fifth-form education, but they were great doctors.

However, the American university wouldn’t give them a medical degree, only a diploma. The idea was that these doctors wouldn’t leave Micronesia — but many went off to Fiji to do another year and get a medical degree. As far as I know, they all stayed in their island states.

And that experience helps you realise that doctoring and medicine, to a great extent, is about practical and human skills — not about academic learning. And that’s what we were able to teach in that limited time.

After a couple of years overseas, I came back to New Zealand, and I went back to the Auckland medical school. But I couldn’t settle down in the city, so we went back to the Bay of Plenty and worked at the Whakatōhea Health Centre with their board and then set up a practice in Rūātoki in 1993.

I had three days a week in the Maaka Clinic at Rūātoki and then, on Thursday mornings, I’d fly up to the Auckland medical school to teach. So that made for an interesting week, particularly because I’d also started a major public health project around the prevention of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

It was in the early 1990s, and the cot death prevention programme of the time simply didn’t work for Māori. The Pākehā babies kind of stopped dying but the prevention programmes didn’t make much difference to Māori babies. So that was a piece of work that I got stuck into. And it was basically about messages not getting to the right places — or messages not being acceptable.

For instance, there were awful messages for Māori mums and whānau. It was like: “Stop bedsharing — that’s so irresponsible. And all that cigarette smoking has to stop too. You’re such bad parents.” It wasn’t quite said like that, but that’s what mums heard.

So we had a team that reworked the messages and reworked the communications pathways, reworked the associated services and worked with coroners, grief counselling, primary care nurses — anyone who would listen to the message of “Māori programmes for Māori peoples”.

In 1996, I went back to med school full-time because, under Professor Colin Mantell, we developed the Department of Māori and Pacific Health. So I taught full-time.

That was good. I was a teacher more than a researcher, although it was during that time that I began to realise that “making change” required research and then writing to demonstrate that what you were doing was the right way to go.

The Māori SIDS deaths began to drop. We wrote about our approach. We looked for other risks that might contribute. We wrote about the experiences of SIDS careworkers, of fathers. We had started a formal programme of research. Hurrah. We were very pleased with that, but university life got a bit torturous, or maybe tedious. And when I did a locum on the East Coast up in Te Puia Hospital in 2001, they asked me: “Would you like to come work for us?”

So, I went with my new partner, Sally Abel, to work again in general practice for Ngāti Porou Hauora. I thought I was leaving the academic world behind.

But that wasn’t the end of your work with SIDS, was it?

I couldn’t let it go. It soon became obvious that although there was a fall in Māori infant deaths at the time, that soon flattened out, and we had to face the real problem which was bed-sharing if there was smoking in pregnancy.

Smoking in pregnancy was a risk anyway. Bed sharing isn’t a risk if you didn’t smoke in pregnancy. But the two of them together are awful. And 30 percent of Māori mums smoke. And 60–70 percent of Māori mums bed-share with their infants. That was the problem.

So we came up with this idea of the wahakura, which is a woven flax bassinet for infants. We said: “What we’ve got to do here is create a safe sleeping space.” In fact, the Māori SIDS prevention team had thought of that three or four years earlier.

But at the time, the whole anti-bed-sharing rhetoric, in the academic world and in the health promotion world, was so strong that we weren’t brave enough to go out there with it and say: “Bugger you. You’ve got it wrong. Actually, we can bed-share and we can bed-share safely.” So we didn’t go there.

But, in 2005, I was on the Coast, and I was surrounded by a Māori world that didn’t give a hoot about academics or professors or any of that sort of thing. We just went for it, and we found a group of weavers who championed the wahakura that we had invented. We tested it. We made it work and we tried it out throughout the Coast. Then we wrote it up and presented it to the world. But the research raised its head again as I realised that we now had to start writing about this innovation and demonstrate why the wahakura works well.

It’s been a great journey which saw another big drop in infant mortality.

I’ve come through the side door in several areas of health. Like falling into general practice and then into community health. And now here I was going into research through the side door. I didn’t plan to go there. It just seemed to be the next thing to do in order to make this thing work.

Over the years, I collaborated on projects with people who knew how to do things. Real researchers who were good at their stuff and who I was able to lean on and learn from. But also able to lead.

I was saying to them: “Here’s the problem. I’ve got some ideas but I need you to help me make this thing work.” And what I found in my research career was that if you’re good to people, they come on board and they do the right thing.

And that was the situation here in the infant death field. But there were also people who were leaders in their own field who needed help with the Māori stuff. And that led to me working in diabetes prevention on the Coast and, later on, in mental health, renal transplant medicine, and food security.

And then Treaty settlements, cultural safety, archiving historical documents and hapū development are other interests that I’ve developed.

I was a teacher more than a researcher, although it was during that time that I began to realise that “making change” required research and then writing to demonstrate that what you were doing was the right way to go.

With you having been there for 40 years at the coalface, so to speak, you’ve been able to take stock of the changes. But what’s the most significant change that you’ve witnessed in Māori health?

The most significant change is that it’s not just me anymore. I’m old enough to remember that, once upon a time, often I was the only Māori in the room in a number of situations in the medical world. That was the same for Papaarangi (Reid) — it was the two of us. But, in this day and age, there are just scores of Māori professionals around.

So that’s number one. There are scores of Māori professionals around.

Number two is that these people are often doubly-skilled. These days, it’s very easy to find Māori doctors who are great doctors who speak the language, who understand the tikanga and, in fact, who came up through kōhanga reo, through kura kaupapa, through whare kura and then into medical school — and who are totally competent and confident. So, workforce-wise, it’s hugely different.

Awareness-wise, it’s hugely different. Once upon a time, we used to have to convince people that actually there was a Māori health problem. People would blame it on socio-economics, genetics, bad behaviour — anything except a poorly performing, racist health system.

Socio-economics was the favourite thing to blame — and it didn’t come out for a decade or two later that, even after you account for socio-economic status, there’s another big difference that can only be explained by racism. So, it’s not just because you’re poor with a bad start, but also because you’re Māori and someone has given you a bum deal.

And the big other thing that’s new now is all the policy that says we must head towards equity — good health outcomes for Māori.

But when you look at what ends up happening, the system isn’t really changing at all. The policies are changing, the workforces are changing, the infrastructure is changing again. But it’s the same old privileged people running things.

There are things that have changed for the better, but getting great change in outcomes is prevented by the huge increase in poverty and inequity. People, I think, are relatively poorer now, and more people live on the edges.

And those social determinants of health are now working against any changes inside the health system being really useful. Does that make sense?

It makes a lot of sense, David. I guess we should touch on the establishment of Te Aka Whai Ora, the Māori Health Authority, which isn’t universally supported. There are many who are saying it’s a separatist approach. But as the old adage goes, if we keep doing what we’ve always done doing, we’ll get what we’ve always had. So it was a bold move by this government.

What were your initial thoughts when it was first mooted? And now that it’s in the stages of being embedded, what are your thoughts on that strategic approach to improve overall Māori health? Are you a Te Aka Whai Ora fan?

Yes, I’m a Te Aka Whai Ora fan. I think it’s correct that if we were in charge of the shape of the services that we wanted to commission, then you’d think they’d be better than the services that were designed by somebody else for us. So, theoretically, that makes sense — and I’m a supporter. And I’m also involved, in the pregnancy and infant area.

But I also think that these big systematic changes in this sort of infrastructure are problematic because they’re so big. And so I see that Te Aka Whai Ora is moving slowly through this process, but, of course, I’m impatient and I want them to move more quickly. And there is a little bit of me that’s worried that we’re just creating a little brown infrastructure next to the white superstructure. I can see that they’ve got some exciting things going on in there that are very much kaupapa Māori. So, yes, it all makes sense.

But I’m worried about resourcing too. It remains to be seen if the government is going to let us fly as opposed to crawl. The proof is in the pudding — it’s in how much resource will stay inside Te Aka Whai Ora and how it will grow in the years to come, especially if we have a government coming in saying they don’t like what’s happening.

Awareness-wise, it’s hugely different. Once upon a time, we used to have to convince people that actually there was a Māori health problem.

You’re now a professor of Māori and Indigenous research at EIT in Hawke’s Bay, and you’ve worked across a number of areas. Can I ask what do you still see as the most pressing health issues for our people?

I think there are two. One is what we eat. You are what you eat. And one of the challenges of modern society is the consumption of mass-produced highly processed foods. They’re cheap, easy to come by, they last a long time in the cupboard, and they’re easy to cook.

We’re no longer eating the food from our gardens, from our chickens, getting seafood from the coast, and killing the occasional mutton to eat. We eat this rubbish, and it’s making us ill, sick, overweight, with diabetes, high blood pressure, and early mortality.

So, eating and food security and food systems are a huge problem, and not just for Māori but for Indigenous peoples across the globe. It’s bigger than governments — it’s about big corporations.

The other thing that I think is huge is mental health. So it might be that Matatini got watched by 15 million people across the globe, and it might be that every government department has a Māori name, and it might be that Māori language is now much more spoken than it ever was in the last 50 years.

But, actually, those of us in the Māori community who are at the hard end of life have got mental health problems like nothing that we’ve ever experienced before.

The stress in our communities is overwhelming and the present health system doesn’t have a way to cope. It just doesn’t have the system set up to deal with people’s distress, and it certainly doesn’t have the systems to deal with the distress of Indigenous peoples, which can be generations long.

The historical trauma of colonisation is another story for another day, but kaupapa Māori solutions for many of our pressing health problems certainly exist. And if Te Aka Whai Ora flies, then a much better future is at hand.

Professor David Tipene-Leach (Pōrangahau, Ngāti Kere and Ngāti Manuhiri) is a Research Professor of Māori and Indigenous Research at the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT). He is an alum of the University of Auckland.

This piece was originally published in the online magazine E-Tangata,"David Tipene-Leach: I wanted to make change", on 23 April 2023 and is published here with their permission.