My tribute to Dame Alison Quentin-Baxter

6 October 2023

Law alumna Dame Alison Quentin-Baxter was the first female head of the legal division at the then External Affairs. Victoria Hallum recounts some of Dame Alison's important life moments.

Dame Alison Burns Quentin-Baxter

28/12/1929 - 30/09/2023

Dame Alison Quentin Baxter, a Law alumna of the University of Auckland, passed away at home in Kelburn, Wellington, aged 93. This tribute to Dame Alison focuses on Alison’s early years when she worked at the then Department of External Affairs. It was written by Victoria Hallam from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT).

In early 2020, Victoria spent time with Dame Alison to interview her for a chapter she was writing on the history of MFAT’s Legal Division for a book on international law in New Zealand (International Law in Aotearoa New Zealand, edited by Dr An Hertogen and Dr Anna Hood, both from the University of Auckland Law School). The following is drawn from Victoria’s interview with Dame Alison for that chapter.

Dame Alison was an extraordinary trailblazer who left a huge imprint as an international and constitutional lawyer. She is also an important part of the history of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, as one of the first women in the Ministry with diplomatic rank and the first to hold the role of head of the Legal Division.

When I was was meeting with Alison for the aforementioned book, Alison was ready for my arrival, having laid out a tray with tea and homemade shortbread. We sat in a nook in her comfortable living room and she recounted her experiences as the Ministry’s first female lawyer during the early years of the Ministry’s existence.

Alison (then Souter) arrived at the Ministry in 1952. She said she could have joined a law firm, having worked as a legal clerk while completing her law degree, but she thought that foreign affairs might be more interesting. She contacted then Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alister McIntosh and asked for an interview. He agreed to meet her and Alison took the train from Auckland for the interview.

She recalled that at the interview McIntosh said if she had been a first-class shorthand typist, he would have gone down on his knees to ask her to join, “But he was less sure about a woman lawyer”.

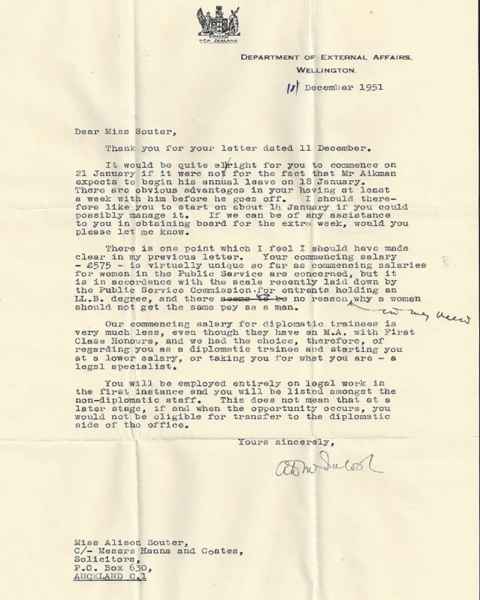

The matter was left to the head of the Legal Division, Colin Aikman, to decide. He offered her a job. She was appointed as a legal specialist but told she could apply for a transfer to the diplomatic side later if she wanted (which she eventually did).

The letter of appointment signed by McIntosh noted that her starting salary was “virtually unique so far as commencing salaries for women in the public service” but that it was in accordance with the scale for entrants with an LLB and “there is no reason in my view, why a woman should not get the same pay as a man”.

The Department of External Affairs was located in an annex on the top floor of the Parliament building and she remembered it as an exciting place to work, with the division bells in Parliament clearly audible. She recalled that the work of the Legal Division at the time involved legal issues to do with the end of the war and making the peace through the United Nations.

She recalled that the practice in the division was that any incoming question would be given to the most junior person and that person would be expected to have a stab at answering it and then it would work its way “up the chain”. She recalls there were an “awful lot of questions” to be answered and that it was a rigorous environment with high standards, but said that once she had completed a few pieces of work on difficult topics such as the ILC’s work on the continental shelf and post-war settlements of confiscated property, she felt “she was in”, and started to be accepted by the others.

A couple of years later, in 1954, she was sent to the Sixth Committee of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) for three months. She recalled coming to work on a Friday and being told that the Secretary wanted to see her. She was told, “Miss Souter, could you go to New York next week?” She was only 24 and had never been overseas but said, “she had the self-confidence of ignorance”. At the time there were two other women in the Sixth Committee, which deals primarily with legal matters, one from Argentina and another from Indonesia and she said they were “extremely supportive”.

She recalled that the ‘winds of change’ were starting. The UN was beginning to change as the newly independent countries were becoming members, and recognition of human rights altered the doctrine that the UN had no jurisdiction to interfere in a country’s affairs. She recalled that “racial discrimination was a live issue” but that “there was not yet any New Zealand interest on the part of the general public. There was no sense that there were implications for the relationship between Māori and the majority of the New Zealand community”. She said she thought she got a favourable report for her time at UNGA; “I was good at finding out what was going on, and I worked hard.”

The letter of appointment from Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alister McIntosh noted that her starting salary was “virtually unique so far as commencing salaries for women in the public service” but that it was in accordance with the scale for entrants with an LLB and “there is no reason in my view, why a woman should not get the same pay as a man”.

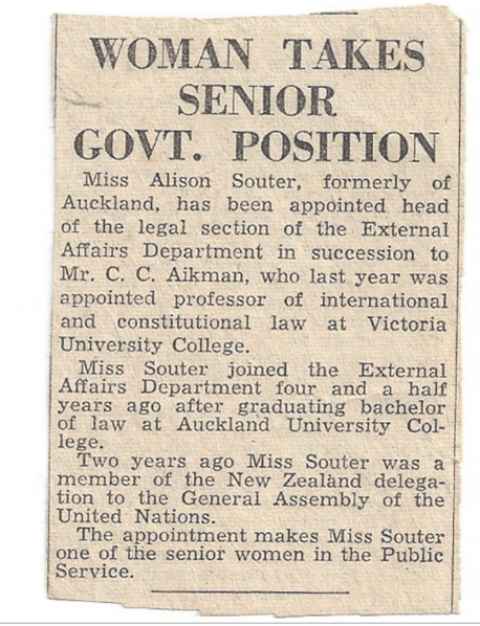

She returned to Wellington to more responsibilities and was formally appointed as head of the Legal Division in 1956 aged 26 when Professor Robert Quentin Quentin-Baxter (her future husband, known as Quentin) left to go on posting to Ottawa. She said that at the time it was really hard for External Affairs to attract good graduates as there were better-paid jobs for newly qualified lawyers in the law firms.

The Department issued a press release about her appointment, which she thought was because it was unusual for a woman to have such a role, and that making it formal would ensure others outside the Department accepted it.

She continued to attend the UNGA and Sixth Committee and was involved in providing advice on the Suez crisis. She was asked by the Ambassador at the time to provide legal arguments for a speech to the New York Bar Association that the actions of France, UK and Israel were self-defence, but said she could not do so as she didn’t consider this to be correct. New Zealand later was one of five countries that voted against the resolution, calling on the three countries to withdraw their forces and reopen the canal.

Alison told me she thought about resigning but decided this wouldn’t achieve anything. Around this time, she was also a member of the delegation to the First Conference on the Law of the Sea (which provided a chance to see Quentin again, as he came from Ottawa to participate). The First Conference on the Law of the Sea wasn’t a great success, but did lead to Alison and Quentin deciding they would get married.

She was posted to Washington in 1960 as First Secretary in the New Zealand Embassy where she worked for a couple of years before announcing her engagement to Quentin who was due to be posted to Tokyo. She applied for leave without pay from the public service, so she could accompany him without having to resign, but the Public Service Commission refused her application on the grounds that there was no basis for leave without pay in such a circumstance.

Accordingly, she had to make a choice between staying at her post or resigning. Of this, she has said, “I was the victim of a mindset that did not then contemplate the possibility that a woman might want to carry on her career after her marriage to a husband that would be happy to see her do so.”

She recalled feeling bereft when Quentin went to work at the Embassy in Tokyo but said she made the most of her time there and enjoyed it.

I was the victim of a mindset that did not then contemplate the possibility that a woman might want to carry on her career after her marriage to a husband that would be happy to see her do so.

Accordingly, at that time, her formal association with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade ended. However, in the tradition of many talented wives of talented men, she continued to work on the sidelines of Quentin’s prestigious legal career. This took her with him to Niue to work on the Niue Constitution and later to the International Court of Justice as a supporting member of the New Zealand legal team in the 1973 Nuclear Tests case.

As Alison put it: “When I went to Niue with Quentin the first time, my fare was paid and it was understood I would help with the work. That became somewhat of a pattern whenever Quentin had responsibility for a major New Zealand government initiative somewhere overseas. My role was accepted by officials and Ministers, most of whom knew me from my days in External Affairs, but it was never suggested I should be paid for any professional work I did in support of the current enterprise. I accepted my role was an extension of the unpaid by nevertheless considerable contribution to international diplomacy made by diplomatic wives.”

Alison made her mark as a constitutional adviser. She took on the role of counsel to the Marshall Islands Constitutional Conventions in her own right from 1977-79, and developed a profile of her own, particularly after Quentin’s early death in 1984. She became the first Director of the New Zealand Law Commission in 1986 and was counsel assisting the Fiji Constitution Review Commission in 1995-96. She advised and wrote extensively on constitutional issues, and was the architect of the Letters Patent 1983 constituting the office of Governor-General of New Zealand.

Many of us have benefited from Alison’s wise counsel over the years. Andrew Townend, who worked with her while in the Legal Division and at the Cabinet Office, commented to me that she understood the Realm of New Zealand better than anyone, having effectively come up with the concept. He recalls her kindness and her extraordinary eye for detail, combined with a profound understanding of the processes that the constitution depends on.

Alison was made a Companion of the Queen’s Service Order in 1993 and a Distinguished Companion (later Dame Companion) of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2007, for services to law. In 2003 she was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws by Victoria University of Wellington where she had lectured. She remained professionally active well into her later years and, together with Professor Janet McLean of the University of Auckland, co-authored the leading text on the Realm of New Zealand, published in 2017 (This Realm of New Zealand, the Sovereign, the Governor General, the Crown).

Alison was a great friend to all of us who had the privilege of working with her. She will be missed.

Kua hinga te tōtara i Te Waonui-a-Tāne. Moe mai rā e Alison, moe mai rā.

FUNERAL

A funeral service will be held at Old Saint Paul’s, Mulgrave Street, Wellington on Monday 9 October at 1pm, followed by private cremation.