Lab discovery offers hope for lymphoedema

18 February 2026

A newly discovered cellular mechanism shows promise for treating painful lymphoedema.

Scientists have made a breakthrough that could lead to effective treatments for lymphoedema, a painful swelling condition for which there is currently no cure.

Lymphoedema can be congenital or caused by an injury, but it mostly occurs as an unintended consequence following breast-cancer treatment.

It occurs when the lymphatic system, which moves fluid throughout the body via specialised vessels, is damaged, leading to fluid accumulation in tissues.

“Our group of researchers has discovered a cellular process that promotes lymphatic vessel growth,” says Dr Jonathan Astin, a senior lecturer in molecular medicine and pathology in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland. See Cell Reports.

“We initially made this discovery in zebrafish but have also shown that the process works in human lymphatic cells.”

The scientists discovered that a growth-promoting molecule, known as ‘insulin-like growth factor’, or IGF, accelerates the growth of lymphatic vessels in zebrafish, so has potential to repair damaged vessels.

They then worked with a University colleague, senior research fellow Dr Justin Rustenhoven, to grow human cells in the lab and found the IGF, could also ‘instruct’ human lymphatic vessels to grow.

While IGF has long been studied, it was not previously known to have this role in promoting lymphatic vessel growth.

“This work is of interest to the medical community as it provides an additional way to induce lymphatic vessel growth,” says Astin.

“This is especially important for people with lymphoedema. In Aotearoa New Zealand, approximately 20 percent of women who have lymph nodes removed as part of breast-cancer treatment will develop lymphoedema, and currently there is no cure.”

The work was conducted in Astin’s lab by then doctoral student Dr Wenxuan Chen and involved collaborations with Dr Kate Lee, Rustenhoven and Professor Stefan Bohlander, all in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, as well as a lab in the US.

“We use fish primarily because they're very simple, but they're still remarkably similar to us,” Astin says.

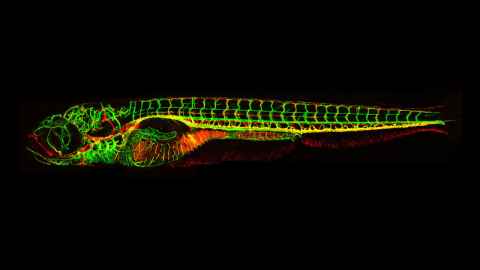

“The advantage of using fish is we can fluorescently label lymphatic vessels so that they glow and then image vessel growth in a whole larva or embryo and not impact its growth at all.

“We can just watch it grow, and things happen much quicker in a fish, because they develop much faster.”

The next step will be to test an IGF based therapy on mice with lymphoedema to see whether it helps.

Astin is cautious about promising too much but says this holds the potential to become a therapy for this painful, incurable condition in the future.

• Read about ‘Openness in the use of animals for research’

Media contact

Jodi Yeats, media adviser Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences

M: 027 202 6372

E: jodi.yeats@auckland.ac.nz