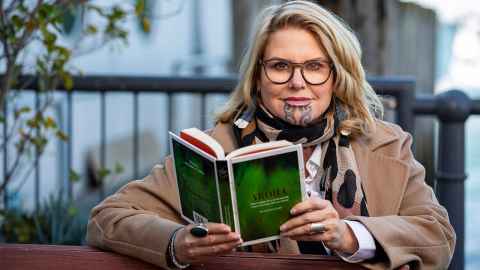

Doctor, now author, Hinemoa Elder shares her Aroha

30 October 2020

Psychiatrist Dr Hinemoa Elder has collated 52 whakataukī (proverbs) in a book called 'Aroha'. She says they reflect Māori wisdom that can help us live harmonious lives. In 2020, they could be just what the doctor ordered.

My mum is still the takere, the hull, of my waka, canoe and my journey is better for that.

“I remember being told I was a ‘TV bimbo’ when I was training in psychiatry, having already completed my medical training,” writes Dr Hinemoa Elder, in one of the many lively personal snippets she drops into Aroha, her new book of whakataukī (proverbs).

“I was blindsided. Those words aimed to put me in a box. Those words were designed to constrain and define me … preclude me from being anything else.”

Hinemoa is a child and adolescent, and youth forensic, psychiatrist as well as Māori strategic leader for Brain Research New Zealand, based in the Anatomy Department at the University. She breaks constraints, opens boxes and defies assumptions – showing they’re irrelevant for everyone.

Why shouldn’t a scientist be glamorous? Why wouldn’t a psychiatrist be concerned about climate change? Why don’t more clinicians promote te reo Māori, given it protects against mental distress and addiction for Māori? And why shouldn’t a leading Māori child psychiatrist be proud of her past, presenting children’s programmes? As she writes: “All the women I know who work in television are skilled and dedicated people.”

We talk via Zoom during Hinemoa’s lunch break at a Milford clinic, under Level Three rāhui. Even under fluorescent lights in an anonymous office, Hinemoa has charisma, her moko kauae framed with earrings of replica white-tipped huia feathers, symbols of mana and leadership. She has described the moko process as “extraordinary”, telling an Auckland Women’s Centre audience earlier this year that the artist, “tohunga of karakia” James Webster, “sent me to another realm. At one point I did feel like I was under the ocean … It was amazing.”

This is what a Māori scientist looks like.

Hinemoa’s path to becoming a scientist began with tragedy. Her mother, Ina, had died of breast cancer in 1991 and Hinemoa took her body to the Medical School. Sir Richard Faull, neuroscientist and director of Brain Research New Zealand, said it was “no small gift”.

“It’s very uncommon in our culture as many of us believe in the sanctity of all parts of the body being buried together,” says Hinemoa. “But as a whānau, we agreed to support her dying wish. It had a profound impact on me that my mother had chosen to do this.”

Sir Richard later became a supervisor for Hinemoa’s PhD and encouraged her to join the brain research team. One of the most influential people in her career, he’s now her boss at Brain Research New Zealand.

“My mum showed the way,” she says.

Ki te kotahi te kākaho, ka whati; ki te kāpuia, e kore e whati. (When a reed stands alone it is vulnerable, but a group of reeds together is unbreakable.)

When Hinemoa suffered another tragedy, her younger brother taking his own life, she says the whānau experience of loss and pain was part of the reason she became a psychiatrist.

“So I could work alongside those with suicidal thoughts, and support them to stay alive and support their families,” she says in Aroha.

“Some might say that is ridiculously impossible. Well, I am all for attempting the seemingly impossible.”

That’s where a proverb like, “Ki te kotahi te kākaho, ka whati; ki te kāpuia, e kore e whati” resonates. It means, “If a reed stands alone, it can be broken; if it is in a group, it cannot,” or “When we stand alone we are vulnerable, but together we are unbreakable”.

These days she’s also a member of the NZ Mental Health Review Tribunal and occasionally guest lectures at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences.

Her activities all seem to work towards a common goal, like strands woven to create one tapestry – one tukutuku panel. The pattern she’s weaving, her kaupapa, is perhaps summed up by Aroha’s subtitle: Māori Wisdom for a Contented Life Lived in Harmony with Our Planet. The well-being of people and Earth are inter-connected – and she says we need to value Indigenous knowledge to get there.

Case in point: in her doctoral research, Hinemoa developed a clinical tool, Te Waka Oranga, that recognises that cultural and whānau knowledge – not just clinical knowledge – are essential for assisting children and rangatahi recovering from traumatic brain injury.

Hinemoa recorded Indigenous knowledge through wānanga (learning) on marae and was guided by whakapapa (in her case, Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī, Te Rarawa and Ngāpuhi). “I went home [to ancestral whenua in the Far North] to ask permission to do research regarding the brain, the head, a sacred part of the body.

“One kaumatua said ‘yes, you can do that, but you have to bring it home first’. So I always brought it home.”

The tool is now used by a rehabilitation centre in Ranui, West Auckland, an impressive direct translation from research to practice.

The book Aroha continues this centring of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). It’s written partially to challenge the idea that Māori culture “is some sort of relic that should just be left in a museum”, preserved and fixed, boxed and labelled. Instead, the book promotes a living, evolving culture, by including whakataukī written by Hinemoa’s own kaiako, her own teachers.

Hinemoa’s hoped-for audience includes those who feel alienated from their own culture, labelling themselves as “plastic Māori”. She describes such harmful terms as internalised colonisation.

“It’s a different kind of infection, if you will. A different kind of virus. The structures of the dominant culture are exquisitely attuned to infecting us with ways to hurt ourselves, and hurt each other.”

But Aroha is warm and perceptive, gently making te ao Māori accessible and relevant to all – through tantalising and sometimes poignant glimpses of her own life.

“My mum continues to have the most critical impact on my life. I have a chat with her most days. She remains my yardstick.

“She is still the takere, the hull, of my waka, canoe, and my journey is better for that.”

Like her fellow local physician writers – playwright/paediatrician Renee Liang, poet/GP Glenn Colquhoun and essayists Emma Espiner (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Porou) and Sylvia Giles, Hinemoa offers stories because “science alone is not going to save us”.

She says we need stories – the traditional vehicle of Indigenous wisdom, encompassing cause-and-effect, empathy and explanation – to make us care.

He aha te kai a te rangatira? He kōrero, he kōrero, he kōrero. Good communication is required for good leadership.

By that – and any other measure – he rangatira ia. Here is a true leader.

PERFECT PROVERB FOR 2020

Whakataukī

He iti hoki te mokoroa nāna i kakati te kahikatea

While the mokoroa grub is small, it cuts through the white pine.

There is power in small things.

“I’ve had days where it’s been tough,” says Hinemoa of the Covid-19 lockdowns.“Life can feel pretty overwhelming. I’ve had to tell myself ‘get up, get out of bed, get dressed. Vacuum the lounge. Put the kettle on, feed the dog’ and I can manage to do those little things.

“So, I have found this whakataukī really comforting, because it reminds me that little things matter.”

Aroha: Māori Wisdom for a Contented Life Lived in Harmony with Our Planet

Penguin Random House, $29.99

This story first appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of Ingenio magazine.