Helping our oceans to flourish again

29 October 2021

Marine science research is breaking new ground in the bountiful benefits mussel reefs can provide and the impact of quieter times for animals under the sea.

A proposal to establish Ahu Moana conservation areas which are co-managed by mana whenua and local communities form part of the Government’s new strategy to revitalise the Hauraki Gulf, and Faculty of Science researchers are leading the way by partnering with iwi to restore long lost mussel reefs.

For Institute of Marine Science Research Fellow Dr Jenny Hillman, collaborations with Ngāti Manuhiri in Kawau Bay and Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei in Okahu Bay are an opportunity to share knowledge and research about mussel restoration. “They’re helping us to co-develop monitoring methods that anyone can then use to track how their restoration efforts are going.”

Funded by multiple donors including The Nature Conservancy, Foundation North’s Gulf Innovation Fund Together (G.I.F.T.) and the George Mason Centre for the Natural Environment, Jenny’s research aims to identify critical knowledge gaps and develop techniques to improve the health, productivity and resilience of coastal ecosystems that have been progressively stripped of mussel populations over the past sixty years.

The healing power of mussels

Since 2013, more than 150 tonnes of the green-lipped shellfish have been placed in the Hauraki Gulf and Marlborough Sounds in the hope that new beds will revive ecosystems by removing suspended sediments from water columns and encourage the return of marine life ranging from microscopic worms to large fish species.

World-first research conducted by Jenny and PhD student Mallory Sea has revealed that mussels enhance denitrification by filtering out harmful nitrogen – something which could help mitigate the worldwide problem of eutrophication. “Eutrophication can be really detrimental, and so showing that something like mussels can help with that is really important,” says Jenny.

Carbon sequestration by mussels is also under the microscope, although Jenny says that building a conceptual model which includes how the molluscs breathe is very complicated because the carbon cycle interacts with the nitrogen cycle “and you’re looking at all these multiple cycles happening at the same time”.

In search of success

Restoring mussel populations is easier said than done. Farmed mussels donated by the seafood industry are a great source, but PhD student Al Alder found that juvenile wild mussels have greater survival rates than juvenile farmed mussels. But while juvenile mussels may be more efficient, they’re also more vulnerable to predators like snapper and rays. Various forms of protection, including the use of coconut matting, fences and cages have been trialled but, as Jenny says, “that’s hard on a large scale because you can’t cage everything”.

Additional research will hopefully identify new techniques to lay and monitor beds – especially given that mussels arrange themselves in different ways at different sites which consequently affects water flows and how sediment gets trapped.

Understanding ‘what success looks like’ is also part of the challenge, and the School of Computer Science is assisting Jenny and PhD student Sophie Roberts to look at different ways to map and model beds with affordable methods – like cameras – that community groups and iwi can use. “The goal for all of us is to make the marine environment better and mussel restoration is only one step,” says Jenny.

Another Faculty of Science researcher who has welcomed the Government’s new strategy to rejuvenate the Hauraki Gulf is School of Biological Sciences and Institute of Marine Science Associate Professor Rochelle Constantine, who studies large marine animals.

Proposed restrictions on commercial and recreational fishing and the extension of marine protection clearly acknowledge multiple stressors on the Gulf ecosystem, however Rochelle says the problem of noise often slips below the radar. “There are many layers of impact from people and one of them is acoustics, and it’s not something that’s often considered.”

Building on previous research by Associate Professor Craig Radford at the Leigh Marine Laboratory, PhD student Louise Wilson is conducting a new study into the sound pollution generated by recreational boaties, who grew to a record 45 percent of the adult population in 2020.

The goal for all of us is to make the marine environment better and mussel restoration is only one step.

Tuning into the Gulf

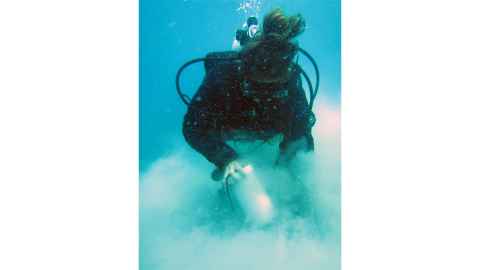

By placing hydrophones on the seabed and using shore-based cameras to match activity on the surface, Louise aims to create a ‘soundscape of the Gulf’ which differentiates between the long-term chronic sound from shipping versus the short-term impulsive and intermittent sound of small boats that manoeuvre and pass by at high speed.

“Smaller vessels usually produce higher frequency sounds and it’s much more intense and also much louder,” says Rochelle, pointing to the potential impact on many different species of fish and invertebrates, like crabs, lobsters, and molluscs, that produce and hear sound that might protect them from predators.

While different animals have different abilities to adapt, Louise points out that many species are “tied to the coast” – unlike larger animals that can move to avoid the impact. “Invertebrates and fish can’t, they’re tied to their habitat. They don’t have the ability to move away from a stressor.”

Silence is golden

While the impact of Covid-19 has increased recreational boating activities, the first major lockdown in early 2020 gave Louise a rare opportunity to establish a crucial baseline. “She had five weeks of basically silence,” says Rochelle, “so we know what these reefs sound like when there’s not lots of boats buzzing around and that is really exciting.”

Without the boats, Louise says, “the range over which these animals communicate demonstrably increased” and knowing what those sounds are in the absence of boats “can help us really know what we should be striving for”.

The research has been primarily funded by G.I.F.T, the Whitney-Chisholm Trust and Auckland Council, and Rochelle says the launch of the University’s new purpose-built research vessel in late 2021 will aid researchers like Louise who need a good platform for diving.

It’s also important, she says, to start having conversations about how to mitigate the amount of noise going into the water, including the possible use of electric boats.

“To have a functioning ecosystem, marine life needs to be able to see and they need to be able to hear. They need to be able to find food, find mates and live their best life. And I think as humans, we’ve really detached ourselves from thinking about how important this is.”

To support vital research on shellfish restoration and fundamentally improve New Zealand’s marine environment, visit: giving.auckland.ac.nz/shellfish

inSCight

This article appears in the 2021 edition of inSCight, the print magazine for Faculty of Science alumni. View more articles from inSCight.

Contact inSCight.