Rosalie Gascoigne: an inspiration to late bloomers

7 November 2023

Associate Professor Linda Tyler explores the story behind a Rosalie Gascoigne artwork in the University Art Collection.

Like they did with Phar Lap and the pavlova, Australians are inclined to claim New Zealand artists as their own, even those who emigrated as older adults, such as Rosalie Gascoigne. An inspiration to late bloomers everywhere, Rosalie was 64 when, in 1981, she was chosen as the first female artist to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale, an achievement made even more remarkable considering her first exhibition had been in 1974 at the age of 57.

Despite her delayed start, Rosalie had a stellar international art career lasting 30 years before her death, aged 82. Her chosen medium was assemblage using found materials. She wrestled huge sheets of corrugated iron, heavy metal signs and countless logs of driftwood onto the roof rack of her station-wagon to cart home and transform in her suburban studio.

Born in Auckland in 1917, Rosalie Norah King Walker grew up in Remuera and went to Epsom Girls’ Grammar where her mother taught. She once said it was her gold gym smock that imbued her with a lifelong love of the colour of pineapple, daffodils and wattle. She graduated with a BA in English and Latin from Auckland University College in 1939, and taught at Whangārei Girls’ then Auckland Girls’ Grammar before marrying fellow Kiwi, astronomer Ben Gascoigne in 1943. Although she left New Zealand when she was 26, she made regular visits home.

Living near Canberra, close to the Mount Stromlo Observatory where Ben worked, was isolating but inspired her as an artist. She started with quilting, gardening and dried flowers before training her three children to scavenge wood, stones and bones for her experimental arrangements. Deploying wood, weeds and wildflowers, she became an acclaimed proponent of the Sogetsu school of ikebana.

“I know I can’t draw,” she would say. “But I can arrange.”

Moving to the suburbs, she started to teach others how to fling materials together with flair, and was commissioned to create displays to impress visiting government dignitaries.

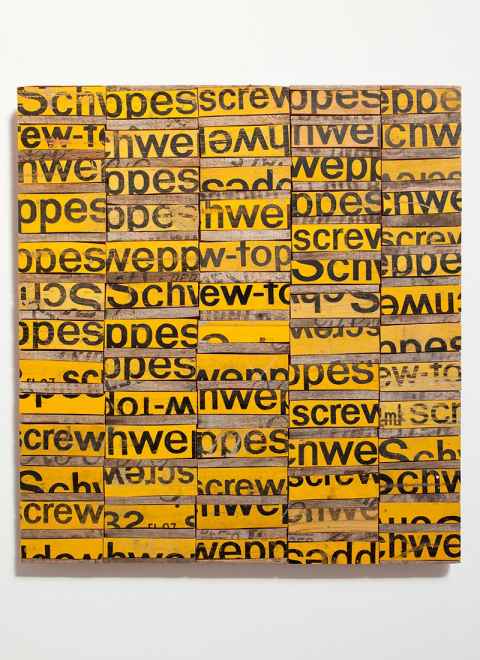

By the early 1970s, when the junk aesthetic of Pop Art was gaining ascendancy and Italian Arte Povera was appearing in art magazines, Rosalie ventured into the art world. The material she used most was what she called “drink crate wood”; dismantled broken boxes collected from outside the soft-drink factory at Queanbeyan.

The yellow and black painted wood had often been damaged by the elements and she wanted to capture this fading, bleaching and warping. The sun hits you like a hammer, she remarked, and bakes the Monaro, a tableland south of Canberra where all trees were felled in the 19th century during pastoralist expansion. Occupied by Aboriginal people for 700 generations and white settlers for just 150 years, Australia, she said, was an epic conjunction of nature and culture that needed to be celebrated for its beauty through a type of art that could evoke boundless space.

Here, the black numbers and text – Schweppes, screw-top, 32 – are shadow to the sunshine. The wattle and daub construction, where wooden uprights woven with horizontal twigs and branches are then daubed with clay to make a building weatherproof, is suggested by the lengthwise yellow and black patterned warp and slimmer light-brown wood wefts. Her title also denotes a construction technique deployed by early colonial settlers, as well as Australia’s national floral emblem, the golden wattle.

Rosalie’s genius was in her transformative construction processes, making labour-intensive yet deceptively simple-looking work. A lover of words as well as images, she scrambles numerals and text to make it abstract, conjuring up the idea of art as a universal language while holding onto pop culture references. Her talent led to major exhibitions, and she was made a member of the Order of Australia for service to the arts in 1994.

Art historian Linda Tyler is the David and Corina Silich Associate Professor in Museums and Cultural Heritage at the University of Auckland.

See pieces in the University’s collection at artcollection.auckland.ac.nz

This story appears in the Spring 2023 edition of Ingenio.