Supply chain security: war and the case for petroleum reserves

Almost two years ago, Covid-19 and the strict lockdown adopted by countries worldwide led to a squeeze in petroleum demand, causing the biggest crisis since the 1970s due to oversupply. Today, the increase in energy prices (electricity and gas prices) due to an increased demand caused by the relaxing of the lockdown measures, and the continuous disruption in the petroleum supply chain, has been made worse by the war in Ukraine.

Soaring gas, electricity and petroleum prices are affecting the production costs of energy-intensive businesses, which, together with the food scarcity due to the destruction of the Ukrainian production and the Russian export ban on commodity products, is reminding many of the 1970s, with an increase in inflation, a high unemployment rate due to the Covid-19 crisis, and soaring petroleum and gas prices.

Today, as in the 1970s, the reason for the crisis is a clash of civilisations. Then, it was a conflict between Western and Middle Eastern countries. Today the conflict between Western countries and Russia seems to be the main reason for this crisis. Interestingly, what we observe currently is not a simple supply chain disruption caused by the uncertainty associated with Russian exports but an unprecedented US embargo on importing Russian energy products.

For all these reasons, the petroleum bear market, which was over ten years old, seems to be ending. WTI prices which were at the highest level in 2008, at about $145/bbl, had their lowest level ever registered of $-37/bbl on April 20, 2020 and are now rapidly growing and approaching record highs ($119/bbl on March 7, 2022), as represented in Figure 1.

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) has been used in the past to address supply chain disruptions. In Western countries, the members of the International Energy Agency (IEA) have agreed to hold total petroleum reserves equivalent to at least 90 days of net imports as a policy to mitigate the risk of severe supply disruptions. These reserves are used when there are supply disruptions

On November 23 2021, US President Biden announced a release from the strategic petroleum reserve of 50 million barrels to decrease the prices paid by petroleum products by Americans, which were increasing due to a mismatch between increasing demand (as countries started relaxing the lockdown measures) and supply that was still disrupted.

Nonetheless, only 18 million barrels represent a permanent reduction, with the remaining 32 million to be repurchased after the prices decrease. Then, on March 1 2022, due to the war in Ukraine and the embargo by Western countries on Russia, President Biden announced the release of an additional 30 million barrels from the SPR, with the other IEA countries releasing 30 million barrels from their strategic reserves as well. At the same time, IEA countries committed to accelerating energy diversification in Europe with additional investment in clean energy and reducing energy dependency from Russia.

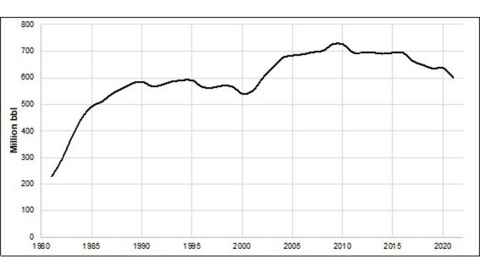

Going back to the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, then US President Donald Trump announced in March 2020 that the SPR would be allowed to buy 77 million barrels to increase crude prices and protect the revenue of small shale oil producers in the US. The purchase did happen, as depicted in Figure 2, but the path to slowly reducing the SPR was retaken soon after and was the dominating policy in 2021.

However, given the size of the SPR of about 600 million barrels, the announced reduction of 30 million barrels was very limited, and this policy suggested that perhaps the reserves were destined to be used during an even stronger disruptive event.

This policy was altered again on March 31 2022, with a new plan from the White House to address the supply chain disruption caused by the war in Ukraine. The plan's main goal is to increase US energy independence by increasing domestic production in the short-term and increasing clean energy production (together with a reduction in petroleum consumption) in the long term.

The first part of the plan is based on increasing supply with a record release of 180 million barrels (1 million per day) from the SPR. At the same time, the White House wants to make companies owning permits to extract petroleum on federal land pay a fee for each idle well and unused acre. The second part of the plan is based on promoting electric vehicles, solar power production and supporting the production of large-scale batteries using domestically extracted minerals, ensuring independence from China. Finally, the US is able and willing to use the strategic reserves to their full extent. In 2022 the SPR is finally to be deployed for the purpose it was originally planned: to meet the challenges of a politically driven supply chain disruption.

A broader concept of security of supply, based on an agile supply chain and energy diversification seems to be the long-term project of IEA countries. Nevertheless, there is a contradiction at the core of the energy policy. IEA countries have been reducing the subsidies for clean energy production (solar and wind) and are now promoting petroleum consumption, both with price controls and subsidising diesel and gasoline prices.

Would it not make more sense to let free markets act and the increase in petroleum prices propel the use of renewable energy, the reduction of CO2 emissions, and the creation of jobs in green industries? Is the SPR protecting western economies or prolonging, unnecessarily, their dependence on petroleum?